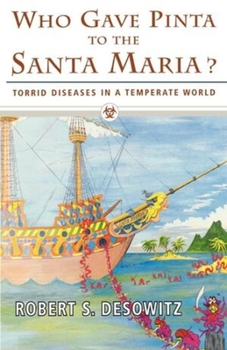

Who Gave Pinta to the Santa Maria?: Torrid Diseases in a Temperate World

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Past--and present--tell us that tropical diseases are as American as the heart attack; yellow fever lived happily for centuries in Philadelphia. Malaria liked it fine in Washington, not to mention in the Carolinas where it took right over. The Ebola virus stopped off in Baltimore, and the Mexican pig tapeworm has settled comfortably among orthodox Jews in Brooklyn. This book starts with the little creatures the first American immigrants brought...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0393332640

ISBN13:9780393332643

Release Date:January 1980

Publisher:W. W. Norton & Company

Length:260 Pages

Weight:0.73 lbs.

Dimensions:0.6" x 5.5" x 8.5"

Customer Reviews

4 ratings

The gift that keeps on giving

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

First, what is pinta, anyway? It's one of four diseases caused by the trypanosome that also causes syphilis and yaws. The Indians gave it to the Spaniards. It was a poor trade, as in exchange they got smallpox, yellow fever and a lot of other unpleasant sicknesses. Anticolonialist literature -- is there any other kind these days? -- always labels these as "European" diseases, although as the historian William McNeill said long ago, most are from Africa. The most important fact to carry away from Professor Desowitz' "Who Gave Pinta to the Santa Maria?" is that "tropical diseases" are not tropical. This is especially so for the worst killer of them all, malaria, which has been Desowitz' lifetime research specialty. Desowitz and I both live in Hawaii, which does not have malaria. The reason is not that Hawaii is too cold. The reason this is important is that the dishonest anti-global warming campaign makes much of the threat that in a warmer world, tropical diseases will move north, where tree huggers who don't give a hoot about 2 million deaths a year from malaria might then have to suffer themselves. True, at least half those 2 million are black, but I think we should count them anyway. Although that is the most important lesson a reader can carry away from this book, given the fact that global warming has assumed a prominence in public debate that it did not have even as recently as 1997, when this book was published, that is not the lesson that Desowitz is hammering, in this and other books. (See my review of his "The Malaria Capers.") He has several. One is the way research money is heaped on trendy topics (molecular biology) while traditional and very effective areas -- including his, parasitological epidemiology -- are starved. Another is that diseases of the impoverished tropics -- impoverished in large part because the people are sick -- are already in the United States and likely to become more troublesome in the 21st century. (In the least satisfying part of the book, he attributes this threat to global warming. It would be the same if the globe were cooling. As he says himself, somewhat contradictorily, "money is the best antimalarial.") His method is to trace the first recognition and exchange of the insect-borne killers, malaria and yellow fever especially, but also Chagas disease, syphilis and its still mysterious cousins, and some others. At times he strays off into invertebrate parasitology (tapeworms, the subject of his earlier book, "New Guinea Tapeworms and Jewish Grandmothers" and hookworm). (All his books are well worth reading.) Then he follows the growing understanding of what the diseases were and how they spread. Between the 1860s and 1890, the basic relationship of humans to insects, other mammals and various viruses, bacilli and other microbes was understood. Southerners, like myself, will find special interest in his lengthy discussion of the disease-load of the South and how John D. Rockefeller made us all he

The particulars of parasites

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Human parasites have been our close companions throughout evolutionary journey. Their complex life cycles are enough to make anybody squeamish. Hookworm larvae, for example, burrow though the skin of bare feet, and chew their way into a blood vessel. They wash through the heart, and lodge inside the delicate capillaries of the lung. The hookworms then crawl up the airways until they are coughed up and swallowed into the digestive tract, forming a blood-sucking worm burden that lays eggs to complete the life cycle through infected human feces. Hard to believe that in areas of the American South up to 12 % of the inhabitants (particularly children) were infected with hookworm less than a hundred years ago. Such subjects become fascinating in the hands of Dr. Desowitz, who never fails to lighten his dark topic with a bit of wry humor. Reading this book is like sitting in on a great medical school lecture that you'll want to remember all your life -- but watch out! You may never want to leave home again! -- Auralgo

A definite read for those interested in epidemiology

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

This is one of the most captivating books on disease written. The facts in this book are far more interesting than any fiction written on the same subjects. Robert S. Desowitz does an excellent job of explaining these topics for those unfamiliar with tropical disease and epidemiology, but doesn't make the book boring for those with a vast knowledge in this area. This is a must read for anyone interested in parasitic diseases.

An interesting but limited discussion of tropical diseases

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

Robert Desowitz's Who gave Pinta to the Santa Maria? (published in other countries under the less silly title of "Tropical Diseases") deals with the spread and treatment of a number of infectious diseases, with emphasis primarily on yellow fever and malaria in North America. The book approaches its subject from a primarily historical standpoint--the chapters are arranged in terms of chronology rather than by disease, and the biological details of the diseases are only discussed to the extent that they're necessary to understand what was happening historically. Desowitz's treatment of the subjects he chooses is generally very good. His style is friendly and readable without particularly ever seeming to be too drawn out, and as a nonspecialist I feel like I learned a fair amount from the book. It's also very interesting, and a bit disturbing, to read Desowitz's speculations about what lies ahead for infectious diseases in the new century. However, the scope of the book is a little narrower than I would have liked. A number of diseases often viewed as "tropical" in origin--cholera immediately comes to mind--are mentioned only in passing. Also, with the exception of a brief chapter about England, it seems like the only times the book ventures outside the U.S. and its territories (which included Cuba after the Spanish-American War, where the transmission vectors for yellow fever were discovered) is to discuss the efforts of the U.S.-based Rockefeller Foundation. There are a lot of places in the world where infectious diseases are still killing many people, and a number of organizations not based in the U.S. that are working tirelessly to do something about it--it seems like at least a chapter devoted to this would have been in order. That said, Desowitz does a fine job of charting yellow fever, malaria, and a few other diseases (notably Chagas' disease) through American history, and both the stories he tells and the historical facts he reveals are often very interesting. At the very least, Desowitz has convinced me that this is a subject that I ought to read more about.