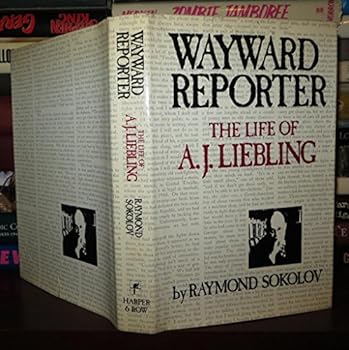

Wayward Reporter: The Life of A. J. Liebling

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

About the first important writer to bridge the area between fiction and objective reporting, where Truman Capote, Norman Mailer, and Tom Wolfe followed him.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0060140615

ISBN13:9780060140618

Release Date:January 1980

Publisher:HarperCollins Publishers

Length:354 Pages

Weight:1.56 lbs.

Customer Reviews

1 rating

Portrait of a

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

Raymond Sokolov has written an extraordinary biography of A.J. Liebling, who was one of the most brilliant and elusive of the "New Yorker" legends. Writing about a writer is hard enough, but writing about this one required not only a thorough knowledge of his work (hard to find, some of his work) but a true ability to enter the man's head, as they say, and tell some of the story from that perch. A. J. Liebling was brilliant and a true connoisseur of all the things he thought were important: food, wine, friendship, writing.Liebling joined the "New Yorker" in 1935, and wrote for it until his death in 1963. He was hired by Harold Ross and his editor was William Shawn. Both in his personal and his professional realms, Liebling was disordered and off kilter, often battered and turbulent, and generally quite exciting. He did not actually finish high school, but was accepted at Dartmouth, from where he was twice expelled for failure to meet the minimum attendance at chapel, so that he did not finish his studies there, either. But he wrote a great deal at Dartmouth, and at the insistence of his father he enrolled in courses at the Pulitzer School of Journalism at Columbia, where he managed to stay for a couple of years; while at Columbia he was assigned to cover police stories, and this lead him to serve as an assistant to well established newspaper reporters and to learn the mechanics of the trade.He married three times, lived in France (wrote many "Letters from Paris") and reported World War II in detail (starting in 1939). He participated in the Normandy landings on D day, whence he produced a particularly memorable piece concerning his experiences on a landing craft. He was there when the Allies entered Paris, and this caused him to write afterwards: "For the first time in my life and probably the last, I have lived for a week in a great city where everybody was happy."Liebling was probably the first to take advantabe of the penumbral area in which fiction and reality are barely discernible from one another, and to exploit it in his writing. Capote followed. He wrote about writing, too, in his classical "Wayward Press" columns of the "New Yorker." He was, in fact, the first serious critic of the press, a job he clearly relished. In people he gravitated towards the odd, the slightly weird, and the eccentrics who had found niches in life from which they they sometimes prospered, often not: in other words, the low life. In New York and London and Paris he consorted and maintained society with strange people, in relationships that spanned decades. These people thought highly of Liebling and what he stood for; what he stood for contained much decency and a total lack of pretension. He spoke to people by remaining silent and letting them speak, something which appears easy but is not. He wrote about the many things he got to understand from these poeple, using clear, simple prose. He was meticulously accurate in his work, aided in this by a formidable memo