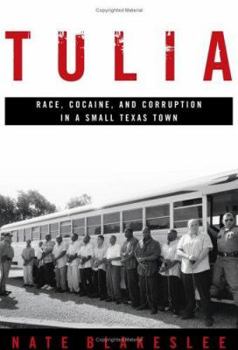

Tulia: Race, Cocaine, and Corruption in a Small Texas Town

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

This true story of race and injustice in a small west Texas town "resembles . . . a modern day To Kill a Mockingbird -- or would, that is, if the novel were a true story and Atticus had won" (New York... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:158648219X

ISBN13:9781586482190

Release Date:September 2005

Publisher:PublicAffairs

Length:450 Pages

Weight:2.40 lbs.

Dimensions:1.4" x 6.3" x 9.6"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Separate and unequal justice under law

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

This is an excellent book. As the definitive treatment of the notorious cocaine stings in Tulia, Texas, it shocks our conscience by revealing how racism still plagues our society and how the unequal application of justice made famous in such books as To Kill a Mockingbird is still with us so many decades later. Add to that that it is superbly written and flows almost like a thriller, and you have an almost perfect book. The immediate subject of Tulia is the arrest of over 40 residents of that small Texas town, almost all of them black, in a 1999 drug sting, and their subsequent treatment by the west Texas judicial system. After the arrests, the book follows two main paths. One covers the trials and convictions--despite many obvious and glaring flaws in the state's cases-- most notably, all of the arrests are made on the word of a single manifestly unreliable undercover cop with a deeply checkered past-- the defendants are railroaded into staggeringly long prison terms, often many decades for one or two alleged sales of small amounts of cocaine. The trials are at best perfunctory-- the local judge and prosecutor both lean hard to obtain convictions, and most of the state-appointed defense lawyers are incompetent or indifferent. Harper Lee never wrote anything as outrageous. The second storyline is that of the people who take it upon themselves to free the defendants. Starting with a few brave local individuals, the effort eventually involves a determined young lawyer from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund as well as pro bono lawyers from some of the nation's top law firms. The resulting court maneuvers make for riveting and almost inspiring reading. All of this is deftly woven together by author Nate Blakeslee, who modestly downplays his own involvement in the case--as a writer for the Texas Observer, he writes an investigative story about the Tulia cases that is later used to attract national attention. Beyond simply describing the arrests and the court cases, Blakeslee takes us into the history and culture of rural west Texas and gives us a more complicated view of the people than the basic story would suggest. This book is highly recommended particularly for those who are interested in race relations in American history, or those who enjoy books on legal cases (such as A Civil Action), or indeed everyone who likes to read, and probably most people who don't.

INVESTIGATIVE REPORTING AT ITS FINEST...

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

This is a superlative expose of what happened in Tulia, a small, dusty town in the Texas Panhandle. Beautifully written, it tells a compelling story of justice denied, thanks to a corrupt group of law enforcement officials and a rogue, undercover narcotics cop. As a career prosecutor for over twenty years, I was appalled at the events that unfolded within the pages of this absorbing book. It is the role of a prosecutor to seek justice. It is not the role of a prosecutor to behave in the reprehensible and despicable fashion that Terry McEachern, the prosecutor in Tulia did. I only hope that he will eventually be disbarred, if he has not already been disbarred for his complicity in the travesty of justice that occurred in Tulia. In 1999, about twenty percent of the adult Black population of Tulia found itself arrested. Pulled out of their homes in the wee hours of the morning in all stages of dishabille, all found themselves accused of selling cocaine to Tom Coleman, an undercover cop who would prove to be something other than what he seemed. His true colors, however, would not come to light publicly until after he was named Officer of the Year. It would turn out that Coleman's only claim to fame was the fact that his father had been a member of that hardy breed of lauded officers known as the Texas Rangers. He was, evidently, nothing like his father, who was by all accounts a well-respected lawman. The only saving grace for his father is that he mercifully died before his son's infamy came to light. Of course, it should be noted that Tom Coleman was able to operate as he did, thanks to the Sheriff of Tulia, Larry Stewart, who supported Coleman until the bitter end. Sheriff Stewart was not worthy of the shield that he wore. Coleman's undercover work was like no undercover work I have ever come across as a career prosecutor. The caliber of his work, which was highly suspect, was such that it would be totally laughable, were it not for the fact that most of the accused found themselves convicted on the word of this less than credible witness against them and sentenced to draconian sentences worthy of murderers. Ed Self, the judge who presided over the trials, did not seem to understand the applicable law and did not ensure that the defendants had a fair trial. He is certainly not worthy of the robe that he wears, and the prosecutor, as I said, should be disbarred for his complicity in this debacle. Many of the defense attorneys were also appalling, providing, at best, ineffective assistance of counsel to their hapless clients. There were some defense attorneys, however, who tried to do the right thing by their clients. The problem, however, was that they did not have all the information at their disposal that the prosecution was ethically obligated to give them, so their efforts were handicapped. Thanks, however, to the efforts of some outraged townspeople and local attorneys, the NAACP's Legal Defense Fund, and the pro bono efforts of a n

Born Under A Bad Sign

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

"TULIA: Race, Cocaine, and Corruption in a Small Texas Town" can be read any number of ways: as a legal thriller; a true crime tale; a sociological case study of a town and its people; an examination of the innerworkings of law enforcement across local, state and federal institutions; a hopeful tale of everyday American heroes coming to aid of victims of a renegade cop; an examination of the social and political arrangements that reinforces the interests of the powerful; as a troubling description of an increasingly repressive society reforging formerly blunt instruments of racist control into sharp new weapons of surveillance and incarceration that are guided and informed by a creed of punishment flowing out of hell and damnation readings of the Bible and law enforcement's "three strikes and you're out" ideological counterpart. What "TULIA" shows most compellingly is the extent to which racism, which Blakeslee shows is nowadays most often expressed in economic terms, lies just below the surface in the everyday assumptions of life in small southern towns. While the town's elite knows that the "N" word is no longer acceptable in polite society, they have found ways to enforce the old status quo with a new rhetorical spin. For instance, the head of the Tulia Chamber of Commerce, Lena Barnett, speaking resentfully about county tax money being spent on court appointed attorneys for the 39 African Americans nefariously accused of dealing drugs, says, "If you can't afford insurance, then you don't go to the doctor... If you can't afford to hire a lawyer, then you go without" (page 183). This says much about what towns like Tulia and states like Texas are willing to pay to balance the scales of justice. Blakeslee ties this observation to a larger critique of government spending, pointing out that while white Tulians resent their tax money being spent to defend the legal rights of blacks or on the poverty programs used predominantly by African Americans because of the economic discrimation they suffer under, they conveniently forget the welfare programs that are solidly in place for the white farm owners. Here's Blakeslee in one of his typically insightful examples of how the deck is stacked in favor of those citizens deemed important by the political classes: "The total tax dollars invested in poverty programs in Swisher County, controversial thought it may be is dwarfed by the subsidies the county receives through the various federal farm programs. In 1990, farm subsidies totaled $28.7 million for Swisher County. Much of that money subsidized cotton and wheat grown for the export market, where U.S. farmers would otherwise be unable to compete with low cost operations in Latin American and Asia. The farms that keep the county alive would likely be gone in a generation if the government checks ever stopped arriving, which means that almost everybody in Swisher County, regardless of race, relies on a handout of some kind, either directly or in

Lessons to be Learned from a Bad Situation

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

I find myself with so many conflicting thoughts about this book that I hardly know where to start, so with no particular order in mind: The Drug War: We've fought this battle for a lot of years now. We've assisted in the shooting down and killing of American missionaries in South America. We've put an enormous number of people in prison. And as this book shows, some of them were clearly convicted with false evidence. Do we see any reduction in the amount of drugs being used? Hey guys, the drug war isn't working. Try something different. Police Power: This book shows what corrupt law enforcement can do. Tell me again why we should give these people more power through the Patriot's Act. Capital Punishment: If this kind of false testimony can get people prison sentences of up to 361 years, can you really say that this couldn't happen in a capital crime. And after you kill them, how do you go back to free them and provide restitution? Conclusions: 1. You don't want to live in Texas. Then again our little town has a similar scandal 25 or so years ago of a police force out of control. 2. The case was really broken open by an NAACP lawyer. Where would we turn if we needed such help. 3. This is the story of one town, one situation. How many others exist that we don't know about?

A Nonfiction Legal Thriller

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

One morning in 1999, in the little cow town of Tulia in the Texas panhandle, before the sun came up, a force of state and local police burst into homes, arresting 47 men and women who had no way of anticipating what had hit them. News cameras were there to show the half-dressed suspects being led from their homes. A neighbor exclaimed, "They're arresting all the black folks!" and it must have seemed that way. Those arrested were mostly black, and they were twenty percent of the little town's black adult population. The _Tulia Sentinel_'s headline proclaimed, "Tulia's Streets Cleared of Garbage." The big sting was for drug dealing, leaving some to wonder if there were all those drug dealers, how many drug users were left as their market in such a little place. It wasn't the first tinge of doubt about the arrests, and four years later after a bitter struggle, those found guilty were sprung from prison and the charges were annulled and restitution made. It's a sordid, fascinating study of justice misguided and justice eventually triumphant that casts light on race relations and the national war on drugs, and it is told excitingly in _Tulia: Race, Cocaine, and Corruption in a Small Texas Town_ (PublicAffairs) by Nate Blakeslee. It is smoothly written and even though we know the outcome beforehand since it is not a novel, it has a great deal of suspense and plenty of memorable characters. There are a surfeit of bad guys here, but they all depended on the fraudulent handiwork of Tom Coleman, a scruffy character ("a bad cop from central casting") whose strongest merit was that his father had been a superb Texas Ranger. Coleman's evidence always consisted of his word against that of the suspects; he never had another cop witness his buys and he never had audio or video of them. The sheriff who had hired him from the pool of narcs in the drug force in Amarillo, an upright deacon and leader of his church, was not troubled by such matters. The processes of the trials, and the scant evidence against the defendants, did not bother the judge, nor was he worried that the impoverished suspects were getting proper counsel. Indeed, Texas Attorney General John Cornyn (now a US Senator) presented the award of Officer of the Year to Tom Coleman after the Tulia arrests. The Texas ACLU became involved, and Blakeslee himself wrote newspaper exposés in 2000. After the national press started picking up on the story, a young lawyer at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund began drafting habeas corpus petitions to get the prisoners free, and she got pro bono assistance from large out-of-state law firms. The effort didn't all come from outside Tulia, though. A big part of the story belongs to Gary Gardner, an obese bankrupt farmer good-old-boy and self-trained legal authority who realized that his fellow citizens were being railroaded, and started his own research. At one point he was examining a questionable correction on a document in the case with his microscope t