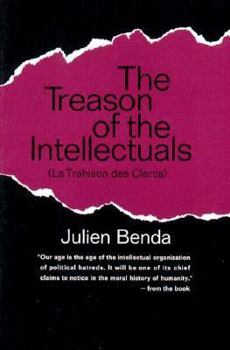

La Trahison des Clercs

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Julien Benda's classic study of 1920s Europe resonates today. The "treason of the intellectuals" is a phrase that evokes much but is inherently ambiguous. The book bearing this title is well known but... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0393004708

ISBN13:9780393004700

Release Date:January 1969

Publisher:W. W. Norton & Company

Length:1 Pages

Weight:0.55 lbs.

Dimensions:0.6" x 5.1" x 7.7"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

A brilliant indictment of incipient pragmatism

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Nietzsche cogently recognized that disinterested reason, when it disinterestedly looks upon its own origins, finds that it is really not so disinterested after all. French intellectuals such as Maurras, Sorel, Péguy and Barrès proclaimed that reason not only must abandon all pretenses of being disinterested, but must even celebrate this abandonment, placing itself enthusiastically in the service of practical interests, particularly of the interests of the race, the nation or the state. Although these thinkers are now remembered, if at all, primarily as progenitors of fascism, their response to Nietzsche remains very much a part of contemporary intellectual life. Benda's indictment of this response in The Treason of the Intellectuals therefore remains very relevant. Benda decries the change in the attitude toward intellectual activity manifested by proto-fascists like Maurras: "Since the Greeks the predominant attitude of thinkers towards intellectual activity was to glorify it insofar as (like aesthetic activity) it finds its satisfaction in itself, apart from any attention to the advantages it may procure. Most thinkers would have agreed with ... Renan's verdict that the man who loves science for its fruits commits the worst of blasphemies. ... The modern `clerks' have violently torn up this charter. They proclaim the intellectual functions are only respectable to the extent that they are bound up with the pursuit of concrete advantage." (p. 151) The "concrete advantage" that was most important to the proto-fascists was of course that of the state. "Up until our own times," Benda reminds us, "men had only received two sorts of teaching in what concerns the relations between politics and morality. One was Plato's and it said: `Morality decides politics'; and the other was Machiavelli's, and it said `Politics have nothing to do with morality.' Today we receive a third. M. Maurras teaches: `Politics decide morality.'" (p. 110) As a result of this "divinizing of politics," the evil which serves politics ceases to be regarded as evil and becomes good. (p. 108) Benda recognizes that the abandonment of intellectual conscience preached by proto-fascists like Maurras is in fact at odds with Nietzsche's thought, but claims that Nietzsche himself is partly to blame for this misinterpretation. Benda cites the observation of Léon Brunschvicg that systems like those of Hegel and Nietzsche "which begin by accepting contradictions, reserving the right to add that they are capable of surmounting them or of 'living' them, lodge their enemy in their midst. Their punishment is that their antithesis still resembles them; and this is what has happened to Nietzsche." (pp. 229-230) Nietzsche insists that intellectual conscience requires recognition of the interestedness of reason, of the fact the reason is always motivated by passion. He further insists that his injunction amor fati requires that we enthusiastically accept this aspect of our present condition. Bu

The roots of totalitarianism and moral relativism

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

I first became aware of this work after seeing that Hayek quoted a lengthy passage of Mr. Benda's book in "The Road to Serfdom". I'm only halfway through "The Treason of the Intellectuals" and I'm impressed with the breadth and depth of Benda's vision. This book's thesis, that the intellectuals have abandoned the study of the universal for the promotion of transitory goals, serves not just as a warning only against those who crave complete submission no matter the reason. It's also a reminder of the finite and fallible nature of Man.

An interesting book

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Well, the title is certainly suggestive. Just who are the intellectuals (or "clercs," as Julien Benda calls them)? And what (or whom) are they betraying? Is the thing they were guilty of in 1927, when Benda wrote this book, still a problem today? It turns out, not surprisingly, that the main duty of the intellectual is indeed to pursue and value truth. And the book is about how this duty fits in with a variety of "racial passions, class passions, and national passions." I have to admit that I'm not quite as leery of nationalism as some others might be. Sure, it sounds like it would be nice if the whole world were a single nation, but judging by what we've seen so far, I think such a nation would be likely to become a global tyranny. I think we're safer with a multitude of nations, so that each group has some protection and so that there can be a little competition in which those nations which mistreat their citizens can be at a long-term disadvantage. On the issue of truth, Benda shows that many people who are supposed to value truth (including academics, journalists, and others) in fact have abandoned it, settling for "national truths" instead. That won't do. Benda explains that we need people to value truths that can be agreed upon independent of our race, class, or nationality. And the betrayal of the intellectuals here is particularly damaging: it risks major wars. Benda was thus able to see that there was a big risk of a huge war, and World War Two proved him right. I think we may be seeing a little of the same problem today when it comes to, for example, the Arab-Israeli conflict. The UN, many journalists, and many academics have substituted ad hoc propaganda for what ought to be truth. And I think that this will indeed not merely preclude peace in the region but lead to one or more very destructive wars. At the end of the book, Benda does indeed discuss peace. And he argues that we are on the wrong track when we try to convince people to live in peace because peace is in their best interest. The argument that war is too destructive is not always convincing. He says it is better to get people to actually desire peace, not merely fear war. I think that's an interesting idea on Benda's part. After all, we have seen numerous examples of a nation being afraid to fight but later becoming strong enough to do just that. In the absence of truth, one does not need to be stronger than one's opponent to pick a fight (let alone any logical justification for doing so). But even people who abide truth may realize that they have indeed become strong enough to become an aggressor to (for example) retrieve land that was stolen a century ago. They may not fear war as much as they fear that failure to act will put them at risk of becoming (or remaining) an oppressed people. Still, is there any way for people to actually become more interested in peace for its own sake? My first reaction was that it is difficult to change human na

A prescient warning of the modern condition which was ignore

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 26 years ago

This prescient warning of what was to come as the intellectuals abandoned their disinterested critique for service to power bears rereading. Only John Ralston Saul in the Unconscious Civilization and Voltaire's Bastards currently makes the case for enlightened values with the fervour of Benda's wistfull invocation of Christ and Socrates.

Strong polemic against abdictation of resposibilty

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 26 years ago

This book should have served as a wake-up call when it first appeared in the twenties. The issue it addresses is as pertinent today as it was then: Intellectuals who abandon their calling to guide and instruct the masses according to the principles of the siecle de lumiere to become apologists for nationalist, irrationalist thoughts and deeds. Everybody who is active in shaping public discourse (politician, writers, especially professors) should head this book's warning and think twice before abdicating his or her responsibility towards society.