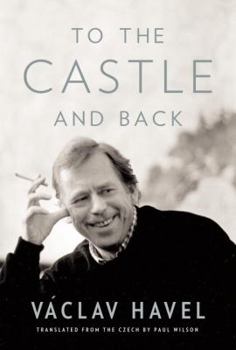

To the Castle and Back

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

From the former president of the Czech Republic comes this first-hand account of his years in office and the transition to democracy following the fall of Communism. A renowned playwright, V clav... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0307266419

ISBN13:9780307266415

Release Date:May 2007

Publisher:Knopf Publishing Group

Length:383 Pages

Weight:1.50 lbs.

Dimensions:1.3" x 6.6" x 9.3"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

(Some of) the reality behind the fairy-tale

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

I will never forget how, during his first mandate as President of Czechoslovakia, Václav Havel mentioned to a journalist that he had learned something utterly, unimaginably absurd about international politics; that even he, as someone hardened by the absurdities of communism, was astonished by it; but that, because of his role, he was not allowed to repeat what he had learned. Like children fooled by the enticement of the unknown, we were all left to hope that the secret would eventually be revealed. Of the many absurdities that Havel documents in this autobiography, one never learns exactly which one had so shaken him, but enough is written to satisfy one's curiosity. Granted his life-long experience with and analysis of the absurd as an outsider and playwright, it was natural for Havel as President to perceive the absurd in the grotesque compromises, ultra petty influences and scarily neurotic personalities of high politics. It's a toss-up which of the two volumes of his autobiography to recommend to those who only have the time for one of them. The first volume, "Disturbing the Peace", covers his life up to becoming a political leader (ca. 1988) and the second, "To the Castle and Back", cover his presidential life from ca. 1989 to 2005. I recommend both, but you should at least read the first volume for the edification of seeing an utterly worthy person on his improbable way to becoming the leader of a country. The second volume is fun, interesting and more recent, but it "only" documents the happily ever after part of the fairy tale narrative of the little guy who beat the communists and then had to run the country himself. Havel says he disliked that narrative, but it did generate huge interest in his person. Here are some remarkable points about Havel. In an early meeting with the departing communist government, his aide's hidden recorder made a racket when it ran out of tape. He contacted fellow national leaders spontaneously to toss around ideas. He counted Richard von Weizsäcker as his closest personal friend but apparently Madeleine Albright did not rate among his friends in the end (page 321). He understood the profound importance of the European Union for ensuring peace, an understanding that is missing in many anti-EU politicians today. He warned George W. Bush twice that his approach to the Iraq war was dangerous and would create more terrorists (page 168). To put it nicely, he was no purist about democracy and believed that referenda should only be used in extremis (page 195). He caught an internal information leaker by telling only that person a story and seeing if it got leaked. He strongly warned that the profit-motive, globalism and consumerism lead to cultural and environmental devastation (page 161) - a point that many global CEOs agreed upon with him. He had genuinely decent experiences with Gorbachev and Yeltsin (good luck doing that with Putin). And sadly, he stopped making jokes in public because they always came back to

(Some of) the reality behind the fairy-tale

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

I will never forget how, during his first mandate as President of Czechoslovakia, Václav Havel mentioned to a journalist that he had learned something utterly, unimaginably absurd about international politics; that even he, as someone hardened by the absurdities of communism, was astonished by it; but that, because of his role, he was not allowed to repeat what he had learned. Like children fooled by the enticement of the unknown, we were all left to hope that the secret would eventually be revealed. Of the many absurdities that Havel documents in this autobiography, one never learns exactly which one had so shaken him, but enough is written to satisfy one's curiosity. Granted his life-long experience with and analysis of the absurd as an outsider and playwright, it was natural for Havel as President to perceive the absurd in the grotesque compromises, ultra petty influences and scarily neurotic personalities of high politics. It's a toss-up which of the two volumes of his autobiography to recommend to those who only have the time for one of them. The first volume, "Disturbing the Peace", covers his life up to becoming a political leader (ca. 1988) and the second, "To the Castle and Back", cover his presidential life from ca. 1989 to 2005. I recommend both, but you should at least read the first volume for the edification of seeing an utterly worthy person on his improbable way to becoming the leader of a country. The second volume is fun, interesting and more recent, but it "only" documents the happily ever after part of the fairy tale narrative of the little guy who beat the communists and then had to run the country himself. Havel says he disliked that narrative, but it did generate huge interest in his person. Here are some remarkable points about Havel. In an early meeting with the departing communist government, his aide's hidden recorder made a racket when it ran out of tape. He contacted fellow national leaders spontaneously to toss around ideas. He counted Richard von Weizsäcker as his closest personal friend but apparently Madeleine Albright did not rate among his friends in the end (page 321). He understood the profound importance of the European Union for ensuring peace, an understanding that is missing in many anti-EU politicians today. He warned George W. Bush twice that his approach to the Iraq war was dangerous and would create more terrorists (page 168). To put it nicely, he was no purist about democracy and believed that referenda should only be used in extremis (page 195). He caught an internal information leaker by telling only that person a story and seeing if it got leaked. He strongly warned that the profit-motive, globalism and consumerism lead to cultural and environmental devastation (page 161) - a point that many global CEOs agreed upon with him. He had genuinely decent experiences with Gorbachev and Yeltsin (good luck doing that with Putin). And sadly, he stopped making jokes in public because they always came back to

Reader as vicarious president

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Vaclav Havel communicates with the open-hearted clarity of a good friend who happens to be a world-class writer. I find myself using his perspectives as I go about my life, far as it is from the great transitions of the Czech and Slovak nations from totalitarianism to democracy. Paul Wilson's translation is superb. Vaclav Havel deserves his reputation as a very human hero.

Fascinating, but not for Havel beginners

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

To those of us deeply involved in Czech history or culture, this is an essential book. It's a fascinating insider's look at the choices a dissident was forced to make when he became President of a postcommunist country. But for people not deeply familiar with Havel's work, this is not the place to start. First read "Open Letters" and "Disturbing the Peace," then John Keane's (similarly unconventional) biography.

Havel in his own words-- and his own style

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Maybe we can be forgiven for wishing that Vaclav Havel, one of the truly amazing figures of our time, had written a more traditional, linear, and straightforward memoir of the Velvet Revolution that brought him to power, and his experiences as president, first of Czechoslovakia, then the Czech Republic. Those were years that pulsed with excitement; and if our hopes that this philosopher-president could remake the world (or his own country, even) in his own image were wildly over-optimistic, then at least his example continues to shine as evidence that history is always unpredictable, and amazing things are truly possible. But instead of a chronological incident-by-incident description of what happened in those years from 1989 onward, Havel has given us this unorothodox book which is divided in three parts: his answers to an interviewer's question (the same interviewer with whom he collaborated on the fascinating "Distrubing the Peace" just before the revolution); excerpts from his official directions to his staff while president; and more recent reflections of his life in the post-presidency (largely written while on sabbatical in the United States). There is plenty here to keep interested people enthralled: insights into contemporary world leaders; descriptions of those heady days which saw one-time "dissidents" elevated to power; explanations of why Havel acted as he did in various issues facing the Czech Republic (much of this material might be pretty much incomprehensible to many non-European readers). We also get stunningly honest glimpses into Havel's personality-- sometimes witty, often persnickety, always overly conflicted. These are, perhaps, the most fascinating aspects of the book (though, from a scholarly viewpoint, perhaps the least important). We learn that Havel loves Americans (so polite [!], he says; such good drivers [!!]; with such beautiful teeth-- though they eat these gigantic sandwiches and wash them down the Coca-cola. Interesting? Maybe. Important? Hardly. Perhaps, from the viewpoint of the student of history and politics, it would have been more useful for Havel to concetrate for a longer time on, say, his relations with Klaus; the problems of privatization; the Czech Republic's relationship to NATO or the EU. But one senses that, had he done so, we would have a much less humane (and human) book here-- and letting personality and humanity shine through beyond the expected constructs of society is what much of Havel's lifework has been about. Certainly, this book irritates at times. Sometimes, one senses that by jumping about from subject to subject, from 2005 to 1994 to 1999 to 2004 again, much is left unsaid and much escapes sufficient analysis. Certainly, there is some kind of absurdist pattern to Havel's repeating certain brief extracts from his journal (about how he wants his pike prepared; the bat in the closet; needing a linger hose for his garden) over and over again. But what that pattern is precisely escapes