You Might Also Enjoy

Book Overview

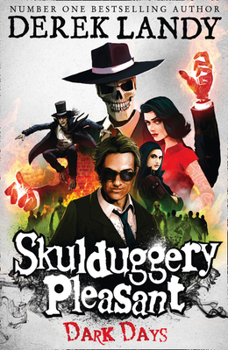

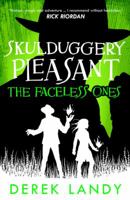

Meet Skulduggery Pleasant: detective, sorcerer, warrior. Oh yes. And dead. Skulduggery Pleasant is gone, sucked into a parallel dimension overrun by the Faceless Ones. If his bones haven't already been turned to dust, chances are he's insane, driven out of his mind by the horror of the ancient gods. There is no official, Sanctuary-approved rescue mission. There is no official plan to save him. But Valkyrie's never had much time for plans. The problem is, even if she can get Skulduggery back, there might not be much left for him to return to. There's a gang of villains bent on destroying the Sanctuary, there are some very powerful people who want Valkyrie dead, and as if all that wasn't enough it looks very likely that a sorcerer named Darquesse is going to kill the world and everyone on it. Skulduggery is gone. All our hopes rest with Valkyrie. The world's weight is on her shoulders, and its fate is in her hands. These are dark days indeed.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0007325975

ISBN13:9780007325979

Release Date:January 2011

Publisher:Harper Collins

Length:415 Pages

Weight:0.79 lbs.

Dimensions:7.8" x 1.1" x 5.1"

Customer Reviews

4 customer ratings | 4 reviews

There are currently no reviews. Be the first to review this work.