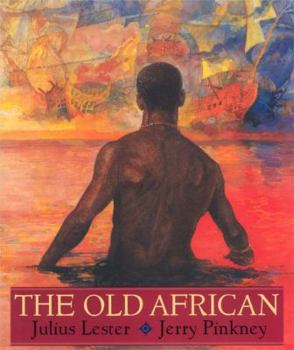

The Old African

No one on the plantation had ever heard the Old African s voice, yet he had spoken to all of them in their minds. For the Old African had the power to see the color of a person s soul and read his... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0803725647

ISBN13:9780803725645

Release Date:September 2005

Publisher:Dial Books

Length:79 Pages

Weight:1.52 lbs.

Dimensions:0.6" x 9.3" x 11.2"

Age Range:5 to 8 years

Grade Range:Preschool to Grade 3

Customer Reviews

3 ratings

The Old African: Humanity's Story, By Jacque Roberts

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Though literally about slavery, suffering, and fantastical escape, The Old African tells a story familiar to us all--the human story, the story of growing up and being ripped apart by the world and each other before remembering our roots and summoning up our inner divinity to return to who we always were. Author Julius Lester and illustrator Jerry Pinkney use a telling structure and bold and vivid imagery, held together by a pearly bubble of magical realism, to quite effectively and beautifully tell the tale of the old African in us all. Thus this books intended audience is all mankind. The story is structured around a flashback; the present sandwiches itself about the past, thus illustrating the importance of remembering our roots and returning to them. It begins with a group of slaves, "a black crescent," watching their master whip a boy--with the old African among them. This first glint of the present establishes a few very important facts: one, that no one has heard the Old African speak; two, that the Old African frightens the slave master; and three, that the Old African uses mystical powers to protect and comfort his people, and in fact still lingers with them in order to do so. Catalyzed by a single thought, a flashback ripples into bright, raw reality and reveals the Old African's past. Jaja was his name and he had had a wife--a soulmate really--and a home and a teacher before another tribe came and captured his entire village for white men, or the "Lords of the Dead." This flashback reveals Jaja's suffering, his travel across great waters, his obligation to be a leader, and his hardening of heart. Awakened from the past, The Old African remembers that the slave holder had said that he had found the beaten boy by the ocean. The ocean! He calls forth the power within himself and finds the ocean from a bird's eye's view. He gathers his people, brings them to the ocean--protected from slave owners by a great lightening storm--and then he assures them life and leads them down into the water on a walk back to Africa. Sea creatures guide them home and they immerge on African soil together with those that had once been lost at sea and soon celebrate their return to freedom, to home. The first two parts of the book--the present and the flashback--are about remembering while the last is about returning. This structure characterizes the human story. It's everywhere. Characters forget who they are and so they go on a journey (whether in thought or in actuality) to remember, and then having remembered, they return home. It is a pattern in every theology, in every beloved, classic story. This story is effective in part because we recognize its structural truth in our own lives. The stunning imagery--both illustrated and written--also brings the message of return to life. At times Pinkney uses bright oranges and blues and yellows--colors reminiscent of Africa--to reveal the roots of the people. The colors serve as images of home and thus b

Can't go over it. Can't go under it. Must go through it.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Julius Lester and Jerry Pinkney may as well just declare themselves the kings of African-American children's literature, cause I can tell you right now that no one is going to contest the title. Virginia Hamilton? She's not making any additional literature at the moment. Leo and Diane Duane? They're far happier illustrating books than doing too much writing. Nope, it all comes down to the dynamite team of Lester & Pinkney. These fellows have it all worked out. They've single-handedly liberated Brer Rabbit from his antiquated vernacular (as in "The Tales of Uncle Remus"), reinvented Little Black Sambo into a far more presentable fellow (as in "Sam and the Tigers"), and even gave "John Henry" his full undeniable due. So where do you go from there? When you've covered everything from black cowboys to old racist standbys, what is there that's left to say? Well, there's always African-American history. In 2004 Virginia Hamilton's, "The People Could Fly" was republished from its short story collection as a picture book with illustrations by the aforementioned Duanes. Now, and in the same vein, Lester and Pinkney bring us their own tale of slavery, the supernatural, and the power of creating new myths from old pains. Our first image in this book is of a boy being mercilessly whipped. A black slave, tied to a tree, has just been recaptured by his master and is paying the price. Fortunately the boy feels no blows and the watching crowd feel no distress. That's because the Old African is amongst them, siphoning off their pain and letting it go. In a flash we see the history of this now mute slave. We see him in Africa captured by a rival tribe. Separated from his wife, Jaja (the Old African's real name) is bought with many others by the crews of several slave ships and must endure unbearable horrors before reaching America. Back in the present, the Old African learns from the whipped boy that the ocean over which the slave ships came is not too far away. Summoning his strength and the people about him, everyone makes a break for freedom by going back to Africa. This time though, they're walking. I've always been a Julius Lester fan but my relationship to Jerry Pinkney has never been an easy one. Quite frankly, he has a tendency to disappoint me. In this book, however, his sometimes sketchy style has been reined in and tightly controlled. In the cover image, Pinkney outdoes himself. He's just as capable of conjuring up a scene of unconscionable horror in the hold of a slave ship as he is able to bring to life the picture of a house in flames with a single yellow skull hanging over the proceedings. His illustrations almost work perfectly in this book up until you get near the end of the tale. Then he starts to do his own thing and loses the audience in the process. For most of the book the Old African in America is seen wearing a brown top hat with a hawk's feather in the brim, a red vest, and a blue sash around his waist.

Richie's Picks: THE OLD AFRICAN

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

The title page of THE OLD AFRICAN is preceded by the pictorial story of the hunt and capture of the runaway called "Paul." "The boy's wrists were tied so that his arms hugged the trunk of the large oak tree. His face was pressed against it as if it were the bosom of the mother he had never known. His back glistened with blood. "Whack!" "The whip cut into his flesh again, but he did not scream or even whimper. "Master Riley had ordered his twenty slaves to watch what happened to someone who dared run away, and like a black crescent moon, they stood in a semicircle near the tree. At the center was the Old African. His face was as expressionless as tree bark. "The slaves did not see the blood on the boy's back nor hear the flies droning around the red gaping wounds. They were staring at a picture in their minds, a picture of water as soft and cool as a lullaby. They did not know how the Old African was able to make them see water as blue as freedom, but he had done it to them often." "Sometimes I feel Like a motherless child Sometimes I feel Like a motherless child A long way From my home, yeah Yeah Sing Freedom Freedom Freedom" --Richie Havens' rewrite of "Motherless Child" I got to attend a Richie Havens performance thirty-five years ago, in 1970. For many of today's young adults, 1970 is ancient history. For me, 1970 was high school and girls and protesting Vietnam, Workingman's Dead, and the first Earth Day. I learned to drive in 1970. The thirty-five years that have passed since then is the same interval of time that separated women getting the right to vote and me getting born. The Nineteenth Amendment once felt like ancient textbook history to me. Not anymore. "It happened so quickly. One minute he had been asleep, one arm across Ola's back. The next there were screams and yells and shouts, and then men bursting into his home and grabbing him and Ola, tying their hands behind their backs and pushing them outside. "Quickly he was separated from Ola. A rope was tied around his waist and then tied to the bound wrists of a man in front of him as his own bound wrists were tied to a rope around the waist of the man behind him." Textbooks and run-of-the-mill history lessons can so easily make the kidnapping, torture, and enslavement of Africans seem like something two-dimensional that happened in history just this side of Columbus discovering the world was round. In contrast, the raw emotion of Julius Lester's text and of Jerry Pinkney's visual artistry in THE OLD AFRICAN give the slave's journey an immediacy that no textbook could ever match. In a work of imagination based upon a true story, THE OLD AFRICAN tells the tale of the slave once known as Jaja, God's gift, who is silent but who has The Power. Jaja, now known as the Old African, recalls his capture, his being traded to the "Mwene Puto, the Lord of the Dead, who was the color of bones," and his subsequent journey across the Water-That-Stretched-Forever, to America. "The bottom