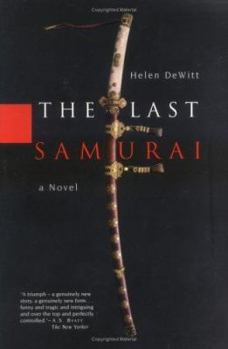

The Last Samurai

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Helen DeWitt's 2000 debut, The Last Samurai, was "destined to become a cult classic" (Miramax). The enterprising publisher sold the rights in twenty countries, so "Why not just, 'destined to become a... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0786887001

ISBN13:9780786887002

Release Date:April 2002

Publisher:Hyperion Books

Length:530 Pages

Weight:1.59 lbs.

Dimensions:1.3" x 6.6" x 8.9"

Related Subjects

Contemporary Domestic Life Fiction Literary Literature & Fiction Short Stories Women's FictionCustomer Reviews

4 ratings

Lessons in irony

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

First, allow me to offer my condolences to those who have classified Helen Dewitt's "The Last Samurai" as "pretentious nattering" and "showing off" (and especially for the egocentric ignoramus who compared this work to sushi with the fatuous claim that "no one really likes it, but they have to say they do, to appear sophisticated"). You missed out on a great novel. The term 'irony' comes from the greek 'eironeia,' meaning feigned ignorance. In modern parlance, irony denotes a discontinuity between what is said and what is meant--the feigned ignorance is on the part of the utterer, not the recipient. Irony is an elitist mechanism, humor for the informed. If you don't know (or at least have a frame of reference for) the source material, you won't get the jokes. Helen Dewitt's "The Last Samurai" is steeped to the gills in irony. No, I do not mean that this work is only for the elite. Unlike T. S. Eliot, who insisted that the various lines of his "Wasteland" not be translated from the Hebrew and Latin, Dewitt translates her foreign words and phrases. Nor do I agree that this novel is a lot of work. Quite the contrary, despite the length, "The Last Samurai" is a quick read (I was disappointed that it was over so soon). You do not have to understand any language but English to understand "The Last Samurai." You don't need to learn the greek alphabet, the hiragana, or any of the kanji, to see what the characters are going through. You do not have to solve any of Ludo's math problems. You don't even have to see Kurosawa's "Seven Samurai" (if you haven't, though, you should). You do, however, have to understand what it means to really want to read a work in its original language. You do, however, have to be able to view learning a foreign alphabet or syllabary as a fruitful endeavor. Most important of all, you do have to understand what it is to want to go on being different despite all the pressures to conform to a standard you know to be lower. One reviewer compared "The Last Samurai" to "Little Man Tate," judging each work as a "thinly veiled portrait of an insecure former 'gifted child.'" Oh, you can positively taste the miasma of working-class snobbery rising off of that line, can't you? Dewitt, in fact, shows us (in Sybilla and her parents) three prime examples of insecure former prodigies, each one having run aground intellectually through slight variations on tangential travel and accompanying enertia. Dewitt focuses a harsh light on Sybilla's inferiority complex throughout the novel. Dewitt succeeds, however, where many works about gifted children fail; whe provides a bildungsroman about a gifted child who is believably gifted, believably a child, and believably maturing. Ludo is insatiably curious, intellectually indefatigable, and lucky enough to have the eidetic memory to support his desires. The only appreciable flaw I could see in the work was the somewhat abrupt insertion of the Japanese piano virtuoso. The ending never quite mitiga

A Tale of Thirst for Knowledge and Hunger for Identity

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was a prodigy. His musical genius was recognized at the age of three. His father oversaw his musical education and supported him throughout his early life. Certainly, Mozart's life would have been dramatically different without the guiding hand of his father.In Helen Dewitt's dazzling novel, The Last Samurai, four-year-old Ludo (the name is Latin for "play, mock") is a prodigy of a different sort. He excels not exclusively in one field, but in whatever he chooses to pursue. By the age of six, Ludo had read the Odyssey and Iliad in Greek, Kalilah wa Dimnah in Arabic, the Book of Jonah in Hebrew, and countless novels in English. He had long been finished with algebra. Learning Japanese became an easy hurdle. Ms. Dewitt brings to life a remarkable child who astounds nearly everyone he meets with his display of intellect at such a young age.But Ludo wanted something that every other child had: a father. Ludo's mother, the complex but likeable Sibylla, tried to augment the child's lack of male role models by frequently watching Akira Kurosawa's masterpiece Seven Samurai. Nevertheless, Ludo longed for a father.At the age of eleven, Ludo finally discovered his father's identity and went to see him, but found him lacking. He then interviewed five different men, with the hope of finding just the right person to become his surrogate father. The six men (his father and the five others) each had to pass a unique test like the samurai in Kurosawa's movie. All six failed. Ms. Dewitt's genius as a storyteller is evident in her ability to avoid a hackneyed plot of single mother/genius son by incorporating Seven Samurai into the narrative, both through quotes from the movie and through the use of similar events.As Ludo wandered the streets of London aimlessly, he stumbled upon an unlikely friend, who realized that both he and Ludo could benefit from each other's talents. This man eventually came to represent everything Ludo wanted in a father. After searching for a male role model, this find was serendipitous. Like Kurosawa, Ms. Dewitt's final "samurai" is an unexpected choice. The book makes you long for the movie; the movie brings you right back to this delightful book.The Last Samurai is a heart-warming tale of a boy who has infinitely more than his peers and yet lacks the one thing they take for granted. The book is generously sprinkled with morsels of humor and maintains a swift pace. The Last Samurai is a remarkable experiment in point of view; Ms. Dewitt transfers dexterously among Sibylla's writing, Ludo's diary, Ludo's first-person accounts, and third-person excerpts about various characters from the past.Ms. Dewitt's writing style evokes a feeling of childish delight, but the reader soon realizes that her words carry much deeper symbolism. She adeptly handles passages usually formidable to writers. Her statements are rarely direct; she is instead the master of the "implied." Her casual writing adds a mask o

A real pleasure

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

The real success of this novel is its ability to draw upon an array of complex philosophical and literary allusions at the same time as it produces rounded, engaging characterizations of its two main characters - Sibylla and Ludo. If I can put it in this way, this book is all about balancing opposites. Its main themes are binaries - for example, East meets West; men and women; parents and children; the intellect and the heart. This novel is as much about the danger of over-educating child prodigies such as Ludo as it is about nurturing them to achieve their potential, whatever that may be. And just as Ludo's voice begins to take over the narrative from his mother, so must he find his own voice and purpose in life.The narrative is discontinuous and stretches from accounts of Sibylla's early family life (her father was a brilliant prodigy whose potential was not properly harnessed by his own severe father), through her own troubled university career, to her son Ludo's quest to find a father-figure amidst several options. Sibylla's connection with Ludo is warm, touching and often very funny. If Ludo occsaionally appears alien and distant to us, it is because he is, after all, a prodigious intellect whose future is as uncertain as the past which he tries to retrieve in his search for his absent father. It's so refreshing to read a book that taxes the mind without taxing one's patience. There are numerous little rewards along the way for those who wish to find them: the name 'Sibylla' evokes the 'Sibyl', the name attributed in Roman mythology to old women who could foresee the future; thus Sibylla in DeWitt's novel tries to map out Ludo's future by teaching him a variety of languages and fortifying his seemingly inexhaustible intellectual resources with more discipline. And I loved the way that Ludo travels along the Circle Line subway reading Homer's 'Iliad' and looking for a father. This mirrors the manner in which Homer's hero, Odysseus (in 'The Odyssey') searches for his wife and son on his epic voyage home from the Trojan War.You would think that a first-time author would fumble and turn these kinds of additional touches into longeurs. But The Last Samurai is a genuine pleasure to read from the first page to the last. DeWitt delivers her lessons as the best teachers do - that is, by capturing her audience's attention and then beguiling her readers with unpredictable tricks and turns along the way. One of the most important of these lessons follows thus: that no human survives without immersing herself or himself in the wonders that the world around us offers. And none of us can access these wonders without first paying attention to ourselves - our self-identies, our minds and our hearts.

Let me be a worthy samurai

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

This book is joyful and thrilling. The intimate and familiar story of a single mother struggling to raise a young son is made original and even epic by the sheer elasticity and power of author Helen DeWitt's imagination. Mother and Son, Sybilla and Ludo, both possessed of gifted and versatile minds, are obsessed with the Kurosawa classic, The Seven Samurai (a film I always felt forced to appreciate until I read this book). Syb uses the film to provide the male role models the boy doesn't have in his life, and Ludo uses it to develop his own version of a Samurai test with which he plans to find the best father possible for himself. Armed with the refrain that 'a good samurai will parry the blow' he sets out to test and win over men of samurai mettle who might recognize his merits. The true joy of reading the book comes in the fact that even though mother and son are both geniuses, multi lingual and well versed in history, literature, math and sciences, thier pursuits in learning and discovery seem exciting and comprehensible. What at first description might sound intellectually intimidating (Ancient Greek, Old Norse, Ptolemaic Alexandria, Fourier Analysis and a blow by blow with variations on the theme of the Rosetta Stone) are made accessible and often hilarious by the dazzling ingenuity and finesse of the wonderful Dewitt. Reading it made me feel I had suddenly come across a vast unrealized potential in myself for the power of creative thought and the ability to comprehend complex ideas. All this disguised in a book of fabulous adventure and tremendous longing.

The Last Samurai Mentions in Our Blog

29 Beach-Perfect Doorstoppers

Published by Ashly Moore Sheldon • August 04, 2024

With your toes in the sand, the sun on your face, and the roar of the surf drowning out your worries, reading at the beach is a double dose of escape. But what makes the perfect beach read? Depends on the reader. If you're looking for a really big book to get lost in, here are 29 beach-perfect doorstoppers for you.