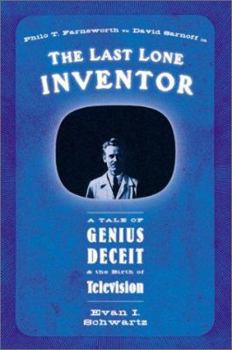

The Last Lone Inventor: A Tale of Genius, Deceit, and the Birth of Television

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In a story that is both of its time and timeless, Evan I. Schwartz tells a tale of genius versus greed, innocence versus deceit, and independent brilliance versus corporate arrogance. Many men have... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0066210690

ISBN13:9780066210698

Release Date:May 2002

Publisher:Harper

Length:336 Pages

Weight:1.17 lbs.

Dimensions:1.1" x 5.5" x 8.3"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

And The Beat-Down Goes On . . .

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

This is an excellent book. I am well-versed in all of the facts it contains through other sources, including some I did not find here, but I enjoy this particular book for its style and pacing. Its like reading a great mystery or adventure tale--which of course it is. The sad thing is, RCA (Specifically, the Sarnoff crowd) continues to hedge and justify and outright ATTACK from their end, even now. There is a blog maintained by the David Sarnoff foundation, which posted a response to "The Farnsworth Invention" back in 2007. The writer not only defended Sarnoff (natural enough), but could not resist taking personal shots at Farnsworth (calling him an un-mentored, uneducated, drunk), the quality of his invention (basically, it was crap compared to RCA & Zworykin), and even calling into question the validity of patent law itself ("You have a patent? What good's a patent?"). It is pretty pathetic. I don't know if I can insert the link, but I'll try. "[...] Many of the allegations made are also completely inaccurate, as anyone who has read this book knows. The Kinescope and Iconoscope actually both required patent clearance from Farnsworth, and it was Farnsworth who built the first "storage" cathode ray tube (pat. no 2087683) not Zworykin.

Quick read, and honest about the prospects of invention

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Evan Schwartz has done an excellent job in creating a fast read without the depth of A Beautiful Mind, but interesting nonetheless. His subject is after all a more straightforward individual than John Nash, although Schwartz, like Sylvia Nasar, does explore some of the darker corners of Farnsworth's personality.Schwartz refreshingly does not engage in positivistic technological whoop-de-doo about the possibility of reviving the status of the lone inventor. During the dot.com boom there was some loose talk about the possibility of the better mousetrap but it is clear that the administered world, that Farnsworth's nemesis in the book (David Sarnoff of RCA) helped to install in the 1920s, makes technological innovation, by the lone inventor, the exception and not the rule.Schwartz also does an excellent job of balancing the two very different (yet strangely alike) personalities of Philo T. Farnsworth versus "General" Sarnoff, who more or less browbeat Dwight Eisenhower into making him a General for Sarnoff's admirable war record.For Philo T. Farnsworth belonged more to the 1890s than the administered, corporate world of the 1920s. His name is somewhat odd in that (like Edward G. Nilges) it confesses an unbroken attachment to a family-of-origin, and a need to at one and the same time identify with a clan, yet precisely identify oneself as an individual within the clan.Sarnoff's name is cooler-sounding and more down-to-business to the modern and indeed the administered ear, and far more than old Philo, Sarnoff was "skilled" (if that is indeed the word) in manipulating, not technical and scientific realities but his relations with his fellow men. Farnsworth was of course no slouch in the PR department, but Sarnoff was more aware that the effect of illusion could be self-reinforcing, and that Sarnoff could USE the technology (and let others tinker with the technology), as in Schwartz' example of Sarnoff's dog and pony show at the 1939 World's Fair.Technicians may cry foul, but the unavoidable fact that one technology builds upon another MEANS that the administered world (in Farnsworth's time, of cheap radio buff magazines, in ours, of cheap personal computers) was brought into being by social engineers *malgre lui* like Sarnoff.But one cannot give old-fashioned credit to the Sarnoffs and the Gates when one admits this fact, and the reason for this is the inseperability of the social illusion they created, and the feeling the rest of us that we have been subtly horn-swoggled.At the 1939 World's Fair, young David Gerlenter was very impressed by what in fact had little relationship to reality but the illusion created by the Fair urged him not only to participate in the creation of the world of "tomorrow", it also made them enthusiastically not question its ideological presumptions.Missing, of necessity, in Evan Schwartz' quick read is another (indirect) employee of David Sarnoff, and this is my cherubic but rather gloomy old pal Theodore Adorno.[The freque

Fascinating and well-executed

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

For science and invention-history buffs, this is a no-brainer, but even the non-technoid layperson will find this a fascinating and fast-paced read. The author does an excellent job of presenting the key characters' development and motiviation, interspersing very fluidly the important biographical details of both Farnsworth and Sarnoff with appropriate and necessary background information on the technological evolution that eventually drew their lives together.Schwartz achieves an entertaining balance between the social history of television and radio, the scientific minutae of the early growth of these technologies, and the personal lives of the individuals involved. Without becoming self-righteous or dogmatic, he lets the reader know where he stands on the issue of scientific integrity versus commercial exploitation, and succeeds in proving his underlying thesis that Farnsworth was truly one of the last of his breed. Finely researched and tightly written, this is a thoroughly enjoyable book.

Farnsworth's Quadruple Victory

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

In The Last Lone Inventor, Evan I. Schwarz shares the birth, growth and maturity of a great mind, and lends some insight into the television industry in its seminal stage.To borrow against another famous inventor's metaphor, Schwarz effectively captures the wonder of inspiration, which is but a small percentage of the process of invention as a whole. From Filo Farnsworth's potato field vision as a mere grammer school teen, to his post-war struggles against competing (and much better financed) visionaries, we see that he posessed one of those rare intellects that is capable of seeing solutions long before "normal" technically inclined people, and with far greater clarity. Farnsworth handily out-classed almost all his TV pioneer contemporaries.Schwarz' story is engaging and hard to put down until the final chapters, where the story loses its momentum a bit (the author provides follow-up on Farnsworth's less spectacular later years, which is interesting but not as intriguing as the discovery of electronic television). The book is also a fine "period piece," in that it reveals picturesque vignettes of the subject's personal life outside the laboratory. And to the author's point (and hence the book's title), it illustrates well the struggles faced by a poorly funded independent inventor, as compared to a well-paid corporate lab engineer working with far better resources.Getting back to Edison's metaphor, while the book amply portrays inspiration, it (wisely perhaps for commercial reasons) ignors much of the "perspiration" that lies between a visionary and his grail. To have explored this deeply would have rendered mundane the main theme of breakneck competitive struggle. Nevertheless, the reader does not grasp the full impact of Farnsworth's triumph until this element is considered -- Farnsworth's success was far more spectacular than even Schwarz reveals!The shortfall can be filled with minor difficulty by the lay reader, and with greater ease by those already familiar with analog electronic communication (i.e., early radio and television). In essence it is this: Normally a lab striving to invent a system of multiple components would do so in an evolutionary process. For example, given the existence of a complete, functional television transmitter, receiver, and picture display apparatus, it would be relatively simple to create, for the first time and with no existing technology from which to begin, a functional television camera. In fact, given that any three of these major elements were already functional, it would be far easier to create any one of the other three. But try to create any two, with just the remaining two from which to base experiments, and the task is exponentially more difficult -- how does the inventor tweak any part of the aparatus when he cannot be sure ALL the other elements are 100% functional? But now consider starting out with ALL FOUR elements missing! That Farnsworth leveraged his creation of electronic television from the

Well-written story of brilliant inventor vs. big corporation

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

This is a fascinating story. I hadn't heard of Philo T. Farnsworth before this book, and as many others, believed that David Sarnoff invented TV. The story of Sarnoff's deliberate attempt to grab the glory and commercial reward of television using every legal and marketing trick at RCA's disposal is surprising and almost unbelievable. The account definitely dispelled my (obviously naïve) belief that individuals who create great inventions are richly rewarded for their contributions. Yet I still found it a generally balanced account - I came away thinking that David Sarnoff was an aggressive, driven, ruthless competitor, but with an appreciation of his accomplishments. Evan Schwartz's writing is clear and enjoyable, and the co-operation of Pem Farnsworth added depth and detail that really brought Philo Farnsworth's tribulations to life.