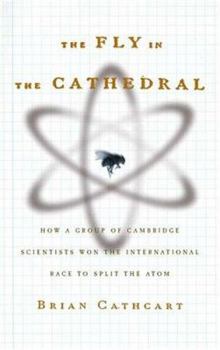

The Fly in the Cathedral: How a Group of Cambridge Scientists Won the International Race to Split the Atom

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

"Cathcart tells this exhilarating story with both verve and precision" --The Sunday Telegraph Re-creating the frustrations, excitements, and obsessions of 1932, the "miracle year" of British physics, Brian Cathcart reveals in rich detail the astonishing story behind the splitting of the atom. The most celebrated scientific experiment of its time, it would lead to one of mankind's most devastating inventions--the atomic bomb. All matter is made mostly...

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0374157162

ISBN13:9780374157166

Release Date:January 2005

Publisher:Farrar Straus Giroux

Length:308 Pages

Weight:1.33 lbs.

Dimensions:1.1" x 6.3" x 9.4"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

A tour of atomic physics in the 1920's

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

The universe is full of empty space. By that I don't mean intergalactic space, but space all around us. Most of everything is simply empty, even so-called solids. The scale of the emptiness within atoms has been likened to a fly within (the space of) a cathedral, and hence the title of the book. After the title, there follows a well-written detective story of which we know the answer. The reader knows the answer, because it is written on the jacket, and, yes, EVERYBODY knows the answer as we have come across the topic before. The story is well told, nevertheless. There is a web of personalities involved, with many interconnectins between the multinational characters. From the people, two distinct points emerge. Firstly, there is the public reaction of what had been achieved in the Cavendish laboratory in Cambridge in the 1920's and early 1930's. The subject matter captured the public imagination, although much of the initial coverage was sensationalist. This was not helped because the one `tame journalist' was not available when the story broke. Headlines about `splitting the atom' were run, and although the author veers away from such terms (as in effect, this had been achieved as early as 1909), the book itself has `won the race to split the atom' as part of its sub-title! Secondly, it very discovery of splitting the nucleus was a very chancy event. The Cavendish laboratory between the wars was not what we would recognise now as `a research establishment'. Everything stopped for tea at 16:00, and there was no work done with equiptment after 18:00. How and why didn't the Americans (with their four centres of research) achieve the desired result first? Many people (if not all concerned) believed that much larger voltages of electricity were required to accelerate particles to `crash' into the nucleus. The final breakthrough was achieved by accident, with a variety of equiptment built up over a number of years, and the operators had to perform gymnastic contortions to avoid electrocution. The equiptment was truly worthy of William Heath Robinson. Brian Cathcard manages to weave an intriguing story, covering a time of intense activity in the nacient science of particle physics. Like many stories of its kind, it raises plenty of questions. It is hard to look at the events of over 70 years ago without realising what has come out of this research. To his credit, the author does not dwell unduly on this. He does quite rightly mention that a number of the people involved did play a part in the development of the atomic bomb. My most endearing memory is of those engaged in research at the Cavendish. I can picture them at work in my mind's eye. A volume that achieves that deserves high praise. Peter Morgan, Bath, UK (morganp@supanet.com)

Dazzling nuclear tale

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

I'm at the University of Cambridge and I knew several of the scientists who feature in this book, as well as being familiar with the colleges and laboratories described. Cathcart has written a gripping tale of scientific discovery. He has been meticulous in his use of archives and other primary sources. On one level this is amost scholarly history. On a different level it is accessible to any reader with a college education in any discipline. The physics necessary to understand the book is given in crystal clear terms. This is a brilliant example of outstanding science writing. The many characters come to life. The period it covers was a golden age for physics in Cambridge, a time when a Nobel prize or two was a routine occurence.,

Splitting the Atom

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

In my school days, I had come across the names of Rutherford, J.J.Thomson and Chadwick but not the two protagonists of this book - John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton. Cockcroft and Walton were the first physicists who successfully 'split' or disintegrated the nucleus. What is interesting about this book is that it manages to provide us with a feel of the excitement and challenges experienced by physicists at the Cavendish Lab during the 1920s-1930s. Most general history of physics tend to focus on ideas and theories but not the nitty gritty aspects of building apparatus and conducting experiments. Instead of taking the former route, this book emphasizes on the importance of empirical physics and its interactions with theoretical physics. At the center of this story is how Cockcroft and Walton raced to build a particle accelerator that is used to bombard the nucleas. But machines are not the central element of the book. The author devotes a great deal of space to building a human aspect of the story. Aside from Cockcroft and Walton, we are are fed with vignettes of Rutherford (who provided crucial leadership at Cavendish) as well as others like Chadwick, Gamow, and the Bohr brothers. A particularly interesting aspect of the book is the competition between the different groups of scientists in different countries (UK, USA, France) working on the same problem. This is more intense given the winner-take-all nature of breakthrough discoveries in term of academic (and public) fame. This book should be of great interest to readers who enjoy reading about the general history of physics. Lack of knowledge or memory of physics would not be an obstacle to the enjoyment of this very readable book. Highly recommended.

The Beginning of Nuclear Physics

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

People had always thought that solid matter was, well, solid. It was only when scientists had an understanding of what atoms were that they began to realize that there were huge spaces between atoms. Later they got to understand that an atom itself consisted mostly of empty space, a big outer shell where electrons whizzed around, containing only a tiny nucleus. The image of the big shell and the tiny nucleus was given by comparison, a comparison that gives the title to _The Fly in the Cathedral: How a Group of Cambridge Scientists Won the International Race to Split the Atom_ (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) by Brian Cathcart. Actually, the atom had been split long before, if the atom, which had been considered indivisible, is split by chipping electrons off that outer cathedral-like shell. But "splitting the atom" has long had the real meaning of splitting the nucleus, and this is the intriguing story of the stolid, energetic and gentlemanly scientists at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge who in 1932 brought forth the birth of nuclear physics. The commanding presence in the book, just as he was as he oversaw the lab, is Sir Earnest Rutherford, a "barreling, thundering, penetrating presence in the world of physics, a great rowdy boy full of ideas and energy." He was thrilled by the ardor of the chase in scientific exploration, and he was an ingenious experimenter, although he was often clumsy with apparatus. In 1927, Rutherford as its president addressed the Royal Society, proposing a new way forward for solving the problem of the composition of the nucleus. If it were possible to accelerate particles artificially, he said, by huge voltages of electricity, they could be slammed against the nucleus and the scattered wreckage analyzed. This sounds completely sensible now, but there was no equipment that could produce such accelerations. The two heroes of this book, John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton, worked in Rutherford's lab, and were easily persuaded to join the chase. Cockcroft was so quiet that his children eventually made the rule that "Daddy could not leave the dinner table until he had uttered two whole sentences." He was superb at designing and making experimental equipment that no one else had thought of before, but was not the experimenter that Rutherford would have liked. Walton was. Another quiet man, he was the son of a minister and a devout Methodist who shunned any activity that might be called frivolous. He came up with the idea of accelerating particles electrically on his own, and when he proposed such work to his boss, Rutherford was of course delighted. In 1932, after almost four years of patient, frustrating, exhausting, and inspiring work, protons bombarded a strip of lithium, and the lithium nucleus cracked open into two helium nuclei. Part of the charm of this book is that it describes work done in a scientific atmosphere that was like none found today. Rutherford, even though a hard taskmaster, insisted t

Exciting account of atomic sudies and early quantum theory

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

I thoroughly enjoyed this book. Maybe it is just me, I relish Scientific American and I as an engineer and I have always been interested in technology and its history. This book made me feel like I was working with Walton and Cockcroft under Rutherford at the famous Cavendish labs in England as they toiled to build a proton accelerator to smash the nucleus before other labs could beat them with cyclotrons and Van de Graf generators. It was an exciting race. It explains how to build a rectifier for 700kv out of huge hand made vacuum tubes. All the big names in early quantum mechanics make an appearance. The politics, the challenges, etc. I highly recommend it.