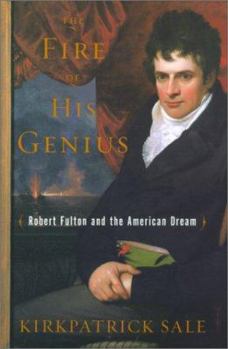

The Fire of His Genius: Robert Fulton and the American Dream

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

None of the spectators who gathered on the Hudson River shore on August 17, 1808, could have known the importance of the object they had come to see and, mostly, deride: Robert Fulton's new steamboat.... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:068486715X

ISBN13:9780684867151

Release Date:September 2001

Publisher:Free Press

Length:256 Pages

Weight:1.00 lbs.

Dimensions:1.0" x 5.7" x 8.6"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Striking a balance

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

In the 100 years after Robert Fulton's death in 1815, biographers produced several accounts of his life. All were largely admiring of his far-reaching achievements, mechanical and intellectual, one to the point of obsequiousness (Thurston, 1878). ( See www.history.rochester.edu/steam for two of them, Thurston and Dickinson, 1913.) Then, after a gap of 60 years, Cynthia Philip provided a different picture of Fulton in "Robert Fulton: A Biography" (1985), which dealt in far greater depth and detail with his personal and business life -- and that paints a picture of a promoter who engages in double-dealing, industrial blackmail and even treason. For the thoroughness of its biographical research, Philip's is the essential Fulton biography now extant. It was followed 15 or so years later by Kirkpatrick Sale's shorter and less formal account ("The Fire of His Genius: Robert Fulton and the American Dream," 2001), which sought to put Fulton's accomplishments in a broader perspective and so shifted the balance back somewhat toward the positive. But not a lot, since the narrative essentially reflects Philip's account. The evolution of the view of Fulton is understandable: To the 19th Century, his achievements were real and palpable; the use of steam power to move people and goods revolutionized transportation and opened the American West (then comprising the land over the Alleghenies), as Kirkpatrick notes; its impact was as great, if less obviously, in a myriad other applications as well. But to the late 20th Century, all those developments are taken for granted or are long forgotten: Steam locomotives no longer move Americans; airplanes do. So today, there's far more room to examine Fulton's life critically. But there's a cost to lost context. The weakness of both Philip's and Sale's accounts is that they are biography, not history: They offer too little perspective to evaluate Fulton personal peccadilloes or intellectual contributions. Was his towering drive to enrich himself and benefit mankind an individual trait, or was it a motivation shared by ambitious men of the age? Were his erratic business relationships a personal fault, or did they reflect the conduct of entrepreneurship of the times? Were his calculations of the benefits of canal construction (an early Fulton passion) a sign of his genius or a common device of canal promoters? Without that kind of background, it's hard for the reader to sort out whether Robert Fulton was really the scoundrel he sometimes seems in the modern biographies or the unequivocal benefactor to mankind of an earlier era that 19th Century biographers depict.

Fulton and America

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

This slim volume (only 250-odd pages) is perhaps more informative than most biographies of Robert Fulton. Author Kirkpatrick Sale has done a marvelous job, in "The Fire of His Genius: Robert Fulton and the American Dream", of capturing the brilliance and the importance of Fulton's vision. Robert Fulton did not invent the steamboat but he did know how to perfect and sell it. This young man led an incredibly full and active life, considering how young he was when he died.But "The Fire of His Genius: Robert Fulton and the American Dream" also differs from other works on Fulton because of the second half of the subtitle: Fulton's influence on America. Much has been made of the New York City that Fulton lived in, and how his work would be part of that city's transformation from a major city in America to an international cosmopolis. (The creation of the Erie Canal in 1820 would really propel that metamorphosis.) But Sale's book also looks beyond the borders of the East and North (or Hudson) Rivers. It takes a long hard look at the westward spreading nation that needed new forms of transportation and a new navy. How Fulton was inextricably wrapped in both concerns is a major component of this very readable book. It helps complete the picture of an era of American History--and of a great American like Robert Fulton--that sorely needed investigation. We are all indebted to Kirkpatrick Sale for this scholarly examination.

A FULL HEAD OF STEAM

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

Today with jet passenger aircraft crisscrossing the country, with nuclear powdered naval craft sailing for months without refueling, and with cruise ships carrying more passengers than the populations of some American Colonial villages, Robert Fulton and the first practical steamboat is largely forgotten. However, the author, Kirkpatrick Sale, states "....the steamboat would be the single most important instrument in the transformation of America in the first half of the nineteenth century: it promoted the penetration and settlement of the American interior...." The text narrates Fulton's life placing him in proper historical context.Chapter 1 is an account of the very successful August 1807 maiden voyage of the Fulton's steamboat, North River (erroneously called the Claremont in textbooks), from New York to Albany and return. Following this successful trip, Fulton initiated regular steamboat service on the Hudson from New York to Albany which ceased only when the Hudson River froze. While not the inventor of the steamboat, Fulton was successful because he built the North River "on sound engineering principles and scientific techniques."The text states that little is known about Fulton's early life, He was born on a farm in 1765 in Pennsylvania to Irish immigrant parents. He developed a strong drive to avoid his father's poverty, and in his mid-teens he moved alone to Philadelphia and was apprenticed to a jeweler. In 1787 he arrived in London (source of funds unknown) for further art study under Benjamin West. It was a difficult time for would-be artists and in 1793 he began devolving into engineering concentrating first on canals. He conceived many inventions such as a marble-cutting saw, a canal-digging engine, prefabricated iron bridges, etc. In 1797 he went to France. Sale gives an intriguing account of Fulton's attempt to sell a submarine and mines (Fulton called them torpedoes) first to Napoleon in France; then later to England when he was rejected by France. Amazingly Fulton tried unsuccessfully to blackmail both countries by threatening to reveal his work to their enemies.In Paris in 1802 Fulton met Robert Livingston who wanted to build and operate a steamboat on the Hudson River. A partnership was formed and Fulton was obligated to build a steamboat to ply the Hudson; however, the author notes "Fulton knew from the outset that it would be on the Mississippi and its major tributaries that the steamboat would have its most consequential impact...." In 1803 he conducted a successful trial run of a prototype steamboat on the Seine, and in December 1806 Fulton returned to America where in 1807 Fulton's commercially successful North River began operations. The book gives a good account of how Fulton and Livingston with state granted monopolies developed steamboat traffic on the Hudson and Mississippi Rivers plus steam ferries to New Jersey. Incredibly, in 1808-09, he lobbied for his torpedoes in Washington.For the 1808 season, Fulton refurbis

American Dream Via Inventiveness

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

It used to be that every kid could name Robert Fulton as the man who invented the steamboat. In the eighteenth century, he was a figure of considerable esteem, as the new American nation prided itself on its inventiveness and its new ways of doing things. Perhaps few kids or adults could now name this once-exalted inventor, and that is too bad, for his invention shaped the new nation in ways that still affect us. A new biography, _The Fire of His Genius: Robert Fulton and the American Dream_ (Free Press) by Kirkpatrick Sale, throws light on Fulton and his invention (or inventions, for he was a constant tinkerer). It also shows him to be one of the most peculiar and self-destructive of inventive men.Brought up in want, Fulton became apprenticed to a jeweler, and learned to paint portraits. He got money somehow, and went to England to improve his painting skills, and did indeed exhibit portraits at the Royal Academy. More importantly, he was fascinated by the British system of canals, and invented a gadgets having to do with them. In France, he tinkered with submarines and naval mines. Back at home on the Hudson, he did the work that made him famous. He made a maiden voyage in 1807 from New York City to Albany, 32 hours in the steamboat _North River_. (It was not the _Clermont_, an error in Fulton's first biography that has been reproduced in countless textbooks.) On the very return trip, he took paying passengers. Though Fulton's boats had a superb record for safety, they caused alarm in those who had never seen anything like them. One spectator wrote that when villagers saw this "strange dark-looking craft... some imagined it to be a sea-monster, whilst others did not hesitate to express their belief that it was a sign of the approaching judgment." Although commercially successful, he spent a great deal of time defending his controversial patent rights and trying to maintain boating monopolies. If he had spent that time improving his products (which were, indeed, superior boats) and arranging for more commercial incursions into such lucrative markets as the Mississippi River (where steamboats forged the most change), he probably would have been richer, happier, and more famous.Sale has taken such facts as are available and with welcome rhetorical flourishes has built a novelistic and satisfying portrait of an enigmatic man. He places both Fulton and the steamboat in a larger history, and just as he is enlightening about the darker or shallower parts of Fulton's character, he is ready to tell about the casualties of the steamboat, such as the Indians or the forests. It is true that America is vastly different because Fulton came along. Mark Twain, who certainly ought to know, wrote "He made the vacant oceans and idle rivers useful, after the unprejudiced had been wondering for years what they were for."

Robert Fulton: A Neglected Subject

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

Author Kirkpatrick Sale has provided us with a well researched book about a historical figure that has been neglected and I learned some interesting facts about Robert Fulton I wasn't aware of. His steamboat was technically called the North River Steamboat. The North River was another name for the Hudson River. Clermont, the name we associate with the steamboat, was a large tract of privately owned land about 90 miles up the Hudson River from New York City. Fulton was also interested in designing a submarine with torpedoes to be used in time of war in addition to underwater cannons and floating mines. He also had a rather curious relationship with a couple named Joel and Ruth Barlow which I will let the reader of the book speculate on. Fulton was plagued by weak lungs due to tuberculois and this ultimately led to his death in 1815. I learned a number of interesting tidbits about Robert Fulton I wasn't aware of, but I have to confess there were parts I read through rather quickly.