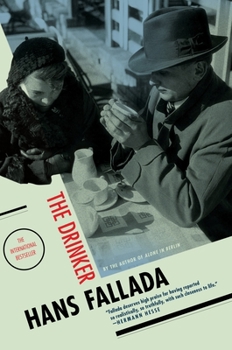

The Drinker

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

One of the great German writers of the 20th century draws from his own life to present a "brave, fearless, and honest" tale of one man's dark descent into depression and alcoholism (The Sunday Times, London) This astonishing, autobiographical tour de force was written by Hans Fallada in an encrypted notebook while he was incarcerated in a Nazi insane asylum. Discovered after his death, it tells the tale--often fierce, often poignant,...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:1933633654

ISBN13:9781933633657

Release Date:March 2009

Publisher:Melville House Publishing

Length:320 Pages

Weight:0.83 lbs.

Dimensions:0.9" x 6.0" x 9.0"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Mid-Life Crisis Turns Man into Low-Life

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

Riveting and devastating, "The Drinker" chronicles one man's rapid descent from the heights--or at least the comfortable ledges--of middle-class respectability, down to the depths of alcoholic degradation. To most normal people, the story will perhaps seem baffling and incomprehensible, even in spite of Fallada's excellent, spare prose; most rational minds will have a hard time comprehending how one man can sink so low, so fast. But alcoholism, alas, is not a rational disease, and anyone who has ever seen the inside of an AA meeting or spent the night in a drunk tank will likely find this novel--particularly its early chapters and its final ones--impossible to put down, or to forget. Fallada's narrator, Herr Sommer, starts as a somewhat well-to-do businessman in Nazi-era Germany, but pretty much skips the social drinking phase of alcoholism and entangles himself in a rapidly worsening cycle of marital strife and monetary struggle, exacerbated by bad schnapps and worse decisions. "Jails, institutions, or death" are frequently cited as the three likely destinations of any alcoholic who chooses to keep drinking; Sommer almost manages to hit for the cycle. For those familiar with the literature of alcoholism, it will probably feel like an extended version of one of those first-person accounts if 1930s-era inebriated insanity that pepper the front of AA's "Big Book." Only for Sommer, there was no opportunity for a feel-good happy ending; rather than Dr Bob and the Good Old-Timers, his deliverance came from doctors and judges who shunted him off to a Nazi insane asylum. This book is reportedly somewhat autobiographical, for Fallada wrote it while confined in such an institution. Remarkably, though, it is relatively free from the twin perilous pillars of alcoholic authordom: self-pity and self-aggrandizement. Instead, it is full of honest writing, lean and spare, full of power and truth. Relatively early on, the narrator--unable or unwilling to maintain the effort needed to keep living the high life, or even the mid-life--tells his wife that people "can feel joy and sorrow down below, Magda, it's just like being up above, it's all the same whether you live up or down. Perhaps the most beautiful thing is to let yourself fall, to shut your eyes and plunge into nothingness, deeper and deeper into nothingness." This is, perhaps, a stretch, for what follows is as ugly, and as compelling, as a car accident. Still, it feels true, in that the alcoholic often secretly longs to simply stop living, without expending the effort or mental energy required for suicide. Those that keep drinking do so because the warm numbing fuzz of inebriation remains infinitely preferable to the bright sharp edges of reality; ultimately, however, their only salvation is oblivion.

Rapture of the Depths

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

The "Drinker", Erwin Sommer, experiences drunkenness as euphoria, a deceptive hallucinatory epiphany, a rush of release from reality and responsibility. I've seen such drunkenness in friends and strangers, but I've never felt it, never completely acknowledged its power until reading this book. That, if nothing more, would make `The Drinker' a book profoundly worth reading. Author Hans Fallada, with his insidiously prosaic prose, drags me vicariously into his drunken rapture even more convincingly than such authentic drunkard novelists as Raymond Carver and Charles Bukowski. And his prose is truly prosaic, both in the original German and in English translation. He was prominent in the between-wars German literary movement called the Neue Sachlichkeit - the New Matter-of-Factness - which devalued literary `effects', but no one who relishes poetic sentences should seek them in The Drinker. Fallada has been described as writing in frantic outbursts. He might best be compared to three other writers who had similar psycho-social weakness, including trouble with alcohol: Jack Kerouac, who wrote in similar manic frenzies and who drank himself to death; Joseph Roth, who wrote with journalistic urgency and who drank himself to death; and Robert Walser, who had no chance to drink himself to death because he committed himself to a mental asylum in which he spent the latter share of his life. Fallada was a better writer than Kerouac simply because his material was better. Roth wrote with equally deceptive simplicity but had a much finer poet's ear for language, a brilliant way of turning decription into metaphor. Walser, a generation older than Fallada, is perhaps the closest match-up; both writers knew what `madness' really felt like, and both spent time in asylums and prisons. But Walser was a lyricist of the psyche, a writer of whimsy as well as pangs. Both Walser and Fallada were pathological outsiders to their repressed and repressive society, but Fallada's commonplace sorrows were truer to the lives of most people then or now. Only the first half of The Drinker portrays Herr Sommer's precipitous transformation from a respectable middling merchant to a violent, self-destructive drunkard. The second half depicts his miseries in penal custody, first in an ordinary jail, then in a jail-like asylum, a `house of the dead' as he calls it. Most readers, I'm sure, will think immediately of Dostoevsky's House of the Dead and/or Solzhenitsyn's Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch. The comparison is valid; that's the shelf on which this semi-fiction belongs. My psychologist wife and I lay down at bedtime to read Der Trinker/The Drinker side by side, ich auf Deutsch, she in English. That way I could sneak a peek at the translation if a passage eluded me. But my wife laid the book aside after a few chapters. "I'm sorry," she muttered, "but I gave at the clinic." Her diagnosis of Erwin Summer, and by implication of Hans Fallada, was `severe depression, self-medicat

Real Talk

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

An unusual, personal, an utterly real account of one man's addiction, and incarceration in a psychiatric facility during Nazi Germany. A smooth, rythmic read, a powerful portrayal. If you're interested in themes of the individual vs. society, this book will grab you.

Hans Fallada's Devastating Allegory

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Hans Fallada penned "The Drinker" as a man fully aware of the evil that was Hitler's Third Reich: he wrote it while a prisoner in a Nazi insane asylum. While I thoroughly enjoyed the literary history of Fallada's tour de force, "Every Man Dies Alone," I found "The Drinker" to be supremely interesting because it so deftly interweaves symbolism with literature. On its face, it is a tale of alcohol-driven self-destruction. Life for Erwin, the protagonist, progressively becomes worse and worse as he looks to drinking as a cure-all. And the inevitable and inescapable Catch-22 comes to define Erwin: he drinks because he's unhappy, and he's unhappy because he drinks. And yet, as you progress further into Fallada's tale, wishing to learn more about Erwin's cyclical decline, a wave of horrified understanding moves over you. You realize that "The Drinker" isn't a lone German alcoholic. "The Drinker" is Germany, and "the drink" is Nazism. Erwin's emotions and symptoms--despair, scapegoating, loneliness, escape, and a lack of self-awareness--were shared in spades by depression-era Germany. And so, just as Erwin turns a blind eye toward his problems and welcomes his life-wrecking addiction with open arms, economically-savaged Germany turned to Hitler's Third Reich for answers and continued to worship at the feet of the Nazi Party under the illusion of a thousand years of purity and prosperity.

An Infatuation with the Queen of Alcohol

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

I first read Hans Fallada's 'The Drinker' eight years ago and my second reading of it confirms all its macabre power to haunt its readers. Written in just two weeks in a German lunatic asylum in 1944, this hypnotic, compelling story of a respectable businessman's alcohol-induced descent into squalor and psychic collapse will sober its merriest reader. Based on events in Fallada's own life, the novel takes us into the progressively warped worldview of one Erwin Sommer - well off, middle class, insecure; a man who will soon discover all the charm and malignant power of a flight into self-destructice alcoholism. Estrangement, Paranoia and Victimisation are Sommer's travelling companions on this journey with only the passing comfort of the bottle for solace. Despite 'The Drinker' lacking any reference to the events of Germany,1944, the reader will soon find himself wondering to what extent Erwin Sommer's experiences are analogous to the descent of Germany in the years of the Hitler period. 'The Drinker' is not for those seeking a comforting or moral conclusion. For the reader who is fascinated by the extremes of human psychology and experience, this book book will stay etched in your mind.