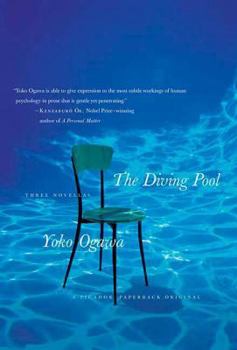

The Diving Pool: Three Novellas

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

The first major English translation of one of contemporary Japan's bestselling and most celebrated authors.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:B00A2LVKBU

ISBN13:9780312426835

Release Date:January 2008

Publisher:Picador USA

Length:176 Pages

Weight:0.47 lbs.

Dimensions:0.5" x 5.4" x 8.2"

Related Subjects

Contemporary Education & Reference Fiction Literary Literature & Fiction Short StoriesCustomer Reviews

5 ratings

Cruelly Beautiful

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

A collection of disturbing stories by one of Japan's foremost contemporary writers, Yoko Ogawa mines the same headspace as Haruki Murakami and Natsuo Karino, with much different results. Whereas Haruki Murakami's protagonist, Boku, is typically a thirty-something, dissatisfied, disconnected, but generally good male, searching for he-knows-not-what, and Natsuo Kirino's violent female protagonists searching for power in the only ways that they know how. Yoko Ogawa's creations are cruel, but only because they can see no other options. I notice from Crazy Fox's review that I am not the only one to connect Murakami and Ogawa. Crazy Fox suggests, "a few recognizably typical tropes (inexplicable disappearance, for instance), it could almost be read as a homage to or parody of Murakami Haruki. And yet one can't shake the sense that Ogawa is pursuing similar themes of alienation and resentment in a slightly different register here in a way all her own," which I heartily agree with. I disagree, though, that the endings are unconvincing or that the cruelty herein is exaggerated. I think that the characters in this book (Aya, the unnamed part-time worker, and the triple amputee), are desperately reaching out to the world around them, perhaps in the only way that they can. As cheindemer suggests in a review largely identical to Yoko Ogawa's Wikipedia article, "her characters often don't seem to know why they're doing what they are," but this is precisely the point. They don't understand their cruelty. They don't understand why they can't reach out with love, and why their attempts to do so are rebuffed, or meaningless. Instead, they must reach out, cruelly and maliciously, to feel that connection, because perhaps only in this fashion can the devastatingly deep crevasses between us be crossed in these tableaux. One reviewer, Jack M. Walter, suggests that, "[Yoko] Ogawa is certainly no Natsuo Karino." I certainly agree, and I couldn't be happier. Having read Real World by Karino, I must say that I find the disconnection between individuals that is arguably examined by the latter is much more reasonably considered here. Karino, at least in Real World, suggested that the disconnection between individuals has become so great that people will overlook practically anything in their desire to feel involved. Ogawa, on the other hand, suggests that people will DO practically anything in their desire to feel involved. The difference here is profound and manifest, making Ogawa's work have an immediate and beautiful impact that Karino is still striving for. The stories in this collection are cruelly beautiful. The aesthetics are disturbingly wonderful. And the characters are chillingly lovable. They are human beings, desperately longing for a connection that they cannot feel. In all, Yoko Ogawa presents a horrible specter of humanity, one that may be all too real. A- Harkius

Wish there was more!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

I am finding myself completely falling in love with Japanese writing. I thought it was just Haruki Murakami, but as I start to expand my horizons, I'm finding more new authors to devour. I found these stories beautifully written, and I wish there had been more. They are dark and haunting and the author succeeds brilliantly at creating a mood. The back says that this is the first major English translation of this author, and I will definitely be hoping for more.

Unfettered, graceful, seductive, soft, and simple

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

I have been dying for some more Ogawa ever since I read two of her short stories in The New Yorker over two years ago and instantly fell for her prose. A novel that was supposed to come out last year never arrived, and it's been one long tease. Ogawa writes with unfettered, graceful prose that is seductive in its softness and simplicity, lending even more shock value to her dark subjects. In the title story, a young girl who grew up in the orphanage run by her parents has grown obsessed with the only boy to ever live there long enough to reach high-school age, and her unfulfilled passions start to emerge in acts of cruelty directed at the home's newest and youngest member. It's disturbing without being exploitative and grotesque. Amidst the calm writing are often wonderful images, such as a snow storm inside the house or lines like "He reappears out of the foam, the rippling surface of the water gathering up like a veil around his shoulders...." Ahhhhh. The second story, "The Pregnancy Diaries," tackles a somewhat commonplace subject in a unique way. A woman keeps a journal chronicling her sister's pregnancy, writing about it in terms evocative of science fiction and horror. Yet, Ogawa does so without straining the metaphor or using obvious language. The final story, "Dormitory," details a woman's return to the spartan housing that was her college apartment, and the strange triple-amputee landlord that lives there. It's a mystery tale, a gothic horror story, and yet also a personal soliloquy. The final image shows her reaching directly in the complex patterns that connect all life. Wonderful stuff. Deep, yet reads like a breeze. Loved it.

Off the Deep End

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

When in doubt, start at the beginning. It only makes sense then that the first book-length translation of fiction by Ogawa Yoko should include three short stories (or "novellas" [sic]) from the years 1990 and 1991, around the time her writing career was just kicking in. And while showing traces of a new writer just getting her bearings in the Japanese literary world, all three stories really stick with you. "The Diving Pool" and "Pregnancy Diary" are quietly chilling and enormously disquieting in their unsentimental and frank exploration of the streak of wanton cruelty and stifled but simmering resentment lurking in the psyches of ordinary, everyday people--a minister's teenage daughter with a girlhood crush and a part-time worker living with her pregnant sister and brother-in-law. Like a good writer, Ogawa shows rather than tells. She is incredibly adroit at using sensual data to get her point across and move the tale along, and the sicky-sweet and sometimes stomach-churning array of tastes, smells, and textures she weaves into her narrative communicates volumes to the attentive reader and lures them inexorably into a virtual synesthetic experience not so welcome in the final analysis. After traipsing through the heart of darkness in humdrum urban Tokyo with these first two stories, you're then easily faked out by "Dormitory," which seems to be falling in the same direction but then throws you for a loop. An offbeat little sketch of a tale, not a single element is jarringly implausible in a discernibly empirical sense and yet the total effect is nonetheless unmistakably surreal. In this as well as a few recognizably typical tropes (inexplicable disappearance, for instance), it could almost be read as a homage to or parody of Murakami Haruki. And yet one can't shake the sense that Ogawa is pursuing similar themes of alienation and resentment in a slightly different register here in a way all her own. As fiction goes, these are not great masterpieces, it must be said. There is something just a bit naggingly unsatisfying and unconvincing about each story, and the exaggerated cruelty Ogawa depicts seems just a tad over the top, as if she's maybe relying on shock value to make some waves. That said, these works show the enormous promise of an up-and coming author who has since established herself securely, and as such they should make quite a splash this side of the Pacific as well.

a good introduction to ogawa

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Oe is quoted as saying, 'Yoko Ogawa is able to give expression to the most subtle workings of human psychology in prose that is gentle yet penetrating,' and that's right, but her characters often don't seem to know why they're doing what they are. She works by accumulation of detail. On the whole, I find her shorter works more satsifying; the slow pace of development in the longer works requires something dramatic to happen to end them in ways which doesn't always come across as convincing. (I've read them in French translation as this is only Ogawa's second book to appear in English. There's a French collection with the same three stories; Snyder's translation of Pregnancy Diary appeared in The New Yorker (in abbreviated form?).) I don't think James Elkins and I disagree that much about what's on the page. It's really a matter of whether the acute descriptions of what the protagonists, all female in this collection and in the majority of Ogawa's other works, observe and feel and their somewhat alienated self-observation is enough. (It is for me; I like her work a lot.) Some of what Elkins sees as 'oddly emotionless and empty' conversations and 'nearly mute and autistic' relationships are, I think -- I'm no expert, a reflection of Japanese society and especially women's roles and standings in it. The three stories are different in tone. 'Dormitory' is more surreal, in a quiet way (less overtly surreal than some of Ogawa's works), and, I think, quietly amusing. 'Pregnancy Diary' and 'Diving Pool' are more of a pair, the latter perhaps less ambiguous, but both are disquieting, the more so as in each the protagonist's motives are opaque to herself.