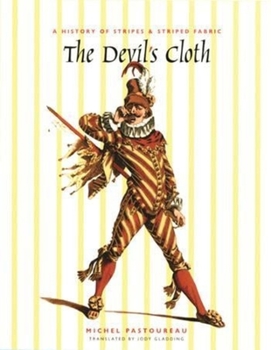

The Devil's Cloth: A History of Stripes and Striped Fabric

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Michel Pastoureau's lively study of stripes offers a unique and engaging perspective on the evolution of fashion, taste, and visual codes in Western culture.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0231123663

ISBN13:9780231123662

Release Date:July 2001

Publisher:Columbia University Press

Length:160 Pages

Weight:0.60 lbs.

Dimensions:0.7" x 5.8" x 7.4"

Grade Range:Postsecondary and higher

Related Subjects

Arts, Music & Photography Decorative Arts & Design Design Europe Fashion Fashion Design Fiction France Graphic Design Historical Study & Educational Resources History Ireland Literature & Fiction Politics & Social Sciences Social History Social Science Social Sciences Textile & Costume WorldCustomer Reviews

5 ratings

A unique and unusual history of stripes and striped fabric

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

Michel Pastoureau's The Devil's Cloth is a unique and unusual history of stripes and striped fabric will appeal to the interested needlecrafter, costumer and quirky artist, as well as anyone else who would receive insights into fashion, styles or changing clothing. From a medieval scandal revolving around striped habits to national stripes and displays of stripes in clothing, The Devil's Cloth is an impressive and scholarly work which is informative reading and an enthuiastically recommended survey.

Lingering Questions

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

Prostitutes, bastards, traitors, Beelzebub, Cain, jugglers, clowns, hangmen, lepers, heretics, adulterous wives and non-Christians were all depicted as wearing and sometimes actually required to wear stripes in the Medieval era. A Middle Ages black hat designation as it were, striped clothing served as a visual shorthand judgement of the person donning such garb. Before eyes could discern more subtle notations, stripes announced a lack of cherished virtue(s), marking the wearer as a person at best on the fringes of the mainstream social mores. Such were stripes-barres.What did striped cloth and clothing mean? Why, indeed, would it mean anything? In the first chapter, Pastoureau muses `The problem of the stripe does indeed lead to pondering the relationship between the visual and the social within a society. He then poses the questions `Why does the West, over the very long term, have the majority of social taxonomies expressed through visual codes? Does the eye classify better than the ear or sense of touch? Is to see to classify? Why is the derogatory sign system-the one that draws attention to outcast individuals, dangerous places or negative virtues, more heavily stressed than the status-enhancing systems?' The questions are disquieting, staccato, sometimes painful. About 225 years ago, the American Revolution's use of stripes was adopted in Europe's changing fashion and social mores. But the pejorative striped garment remained alongside the playful and fashionable stripe as a mark of the social outcast, the inmate, the madman, the thief. What does that say about Western culture? Did we, and do we continue, to use stripes to hold at a safe distance the questionable? Do we use barred barriers to allow us to peer safely onto the unclean, the disturbed without being subject to the reach of their conditions? Is the stripe a visual sign of our attempt to control our surroundings? While pondering the author's questions, the notion of sacred geometries and M.C. Escher returned time and again. Try as I did to expel the distractions of what seemed only marginally related, the nebulous concepts persisted. The unsettling truth is that stripes are an "uncontained," open-ended geometry. Escher's birds and lizards were closed systems, stripes have no end, even when severed, the stripe marches beyond mere visual boundaries. A geometric renegade, stripes defy enclosure in any manner. And we react to them with both caution and delight. This beautifully designed little book falls short only in its visual delivery once opened. I was left wanting full-color plates of the black and white given examples of striped clothing since about 1240. This is a book worth reading and adding to one's library, worth mulling over the questions it asks. Again and again.

Yipes, Stripes!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

Imagine a convict. What sort of clothes is he wearing? Everyone knows, but how is it that this universal sign came to be? That is one of the surprising questions answered in an odd little book about, of all things, stripes. _The Devil's Cloth: A History of Stripes & Striped Fabric_ (Columbia University Press) by Michel Pastoureau (translated from the French by Jody Gladding) shows stripes all over the place and gives a wide-ranging account of just why they have the clothing functions we seem almost instinctively to know about them. The pejorative nature of stripes was founded on a legend sparked in the Bible's pages, and the Carmelite order figured that stripes would be a good uniform for its members, while the members of other orders wore sober solid colors. The Carmelites arrived in Paris in 1254, and were immediate victims of abuse and mockery, with people making jests about how they were just the type to be "behind bars," and so on. The cloaks were a scandal, and Pope Alexander IV expressly ordered unstriped ones for the Carmelites. It didn't do; ten successive popes were required to put the demonic garment down, and even then the Carmelites out in the sticks probably kept it.Stripes were thereby authoritatively banned from religious garb, and they became assigned to nasties: "Treacherous knights, usurping seneschals, adulterous wives, rebel sons, disloyal brothers, cruel dwarfs, greedy servants, they may all be endowed with stripes on heraldry or clothes." Cain and Judas don't always have stripes in their pictures, but they get them more than any other biblical figures. As time went on, the stripe was associated not so much with badness as lowness. Servants wore stripes in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Eventually, the jauntily fashionable folks of those times took to wearing stripes, but wore them vertically, which distinguished them somehow from the reprobates who had to wear them horizontally. Everything changed in 1775, when the pejorative aspect of stripes (which has never completely left) was largely abandoned that they might become the clothing of the revolutions. Stripes became a good thing, but they also remain naughty. Pajamas, underwear, and bedsheets used to be uniformly a pure white, but in the nineteenth century, the white got diluted, either by quiet striping or by pastels. It may be that such striping represents once again the barrier, this time against our own desires and our unquenchable lusts. We are reminded perhaps that we are all potentially as errant as convicts.This is an odd book with both close arguments and speculative hypotheses. It has wonderful footnotes, including one telling how the author's father visited a department store with Picasso, who insisted on ordering pants that would "stripe the ass." Stripes are everywhere, and they mean something, and that meaning has expanded in surprising ways over the centuries. If you like stripes, and who doesn't, you will find that your apprec

Much more than visual history

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

You may not have given much thought to stripes before. Zebras, awnings, prisoners in old movies: stripes may have seemed either unusual (the zebra), somehow functional (traffic crossings) or banal (tee shirts) but in all cases, not particularly meaningful. This book will change all that. It is several things: a scholarly semiology of stripes, a thoughtful and thought-provoking investigation into the variety of historic social meanings of striped surfaces and, best of all, an irresistible initiation to the reader to ponder (under wonderfully playful and able guidance) not only stripes but their significance - both unconscious and deliberate - to the varieties of historic and contemporary human social discourse. It turns out that stripes mean a lot.Michel Pastoureau is an accomplished French paleographer and archivist and an expert on heraldry and other symbology. This book, he informs the reader in his introduction, is the one among the thirty-five he has written that most "truly corresponds to what I had hoped to write at the outset." His idea for the book, as well as his burgeoning interest in, and curiosity about, the stripe derived from his interest in Medievalism. "In medieval dress, everything means something," and therefore he knew he was onto something big ' regarding stripes. Asserting that the stripe is "not a form but a structure," Pastoureau organizes this exposition chronologically, beginning with the 13th century. He explores the history and the meanings of pattern and structure from a social point of view; his knowledge of production methods will please textile historians, and his playful and open-minded approach (he asks a lot of questions, to which there may or may not be answers) incites both awe and curiosity in the reader.The stripe's changing meaning is explored; two chapters, "From the Diabolic to the Domestic," and "From the Domestic to the Romantic" are especially useful. He follows the stripe into its contemporary uses and meanings ("A stripe often leads to a uniform, and the uniform to a penalty.") His discussion of its many roles and ramifications takes off in "Stripes for the Present Time," on contemporary stripes.Pastoureau is eager to share both his sources and his further thoughts, and does so in his 112 generous and interesting endnotes. (He has studied the social meanings of animals and colors, too.) So, for example note 28, on the leopard (for there is a section on spots in this book) remarks " The bad name given to the leopard in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries allows the lion to unload on the leopard all its own negative aspects." There is a good index, too.Far from being merely another little book on a footnote to fashion or art history, this is a scholarly and philosophical work that is by turns deeply playful (Pastoureau discusses striped toothpaste, too), deeply thoughtful, and generously invites the reader to join the conversation. A topic that you might have thought too small or unimportant to be the

What's in a Stripe?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

I had read two reviews of this book that thoroughly peaked my interest before purchasing it. Since The Devil's Cloth deals with a visual subject (the cultural and historical meaning of striped clothing), and since it will most likely appeal to those in visual fields of work and study, it came as something of a suprise when I unpacked this small tidy little book. Barely 100 pages, roughly 5"x7" it contains fewer illustrations than I would have expected and none in color. But clearly what is important here is the text, which is scholarly, well researched, informative and compelling. Beginning in the Middle Ages with a Bilbical interpretation from Leviticus, the author traces the sometimes changing implication of wearing striped patterns. The text contains well documented cases of, as in the order of Carmelite monks, groups of people who were shunned from society for the audacity of wearing stripes. Pastoureau follows the change from horizontal (negative) stripes to the favoring of vertical (positive) stripes made popular at the time of the American Revolution; and equates such change with the overall societal changes coming from the newly created democracies. Overall, it's a quick but interesting read and will make a nice addition to anyone's visual design library.