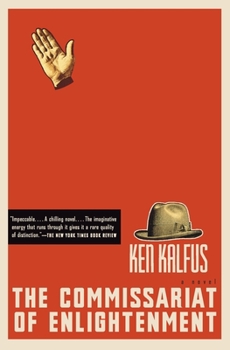

The Commissariat of Enlightenment

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Russia, 1910. Leo Tolstoy lies dying in Astapovo, a remote railway station. Members of the press from around the world have descended upon this sleepy hamlet to record his passing for a public... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0060501391

ISBN13:9780060501396

Release Date:February 2004

Publisher:Ecco Press

Length:304 Pages

Weight:0.60 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 5.3" x 8.0"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Richly imagined

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

The falsification of reality through the use of motion pictures is a fascinating subject, and the scenes in COMMISSARIAT OF ENLIGHTENMENT with the dying Tolstoy and a Pathe film crew are sufficient on their own to earn this novel high praise. The artist, the propagandist, grappling with a new medium can be a rich vein to explore in the right hands, as here. When you add an embalming angle, revolutionary intrigue, surprises, striking characterizations, and a clean prose style, you get a fine, memorable novel. I also have to say that Ken Kalfus earns credit by putting his e-mail address in the back of the book.

Seriously entertaining: the birth of (the Soviet) nation

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

(4 1/2 stars). Four set pieces alone would justify reading of this novel: the making of Tolstoy's death mask (the narrator describes that the cement left one of the Count's recently closed eyes with a little popping sound); a true revolt of the proles unfolds just as the camera man hopes for footage of the same to stand in for the Kremlin where Stalin "might" have been as an extra if he had not really not been there for the October (read: November) revolution; the embalming of Lenin as he/before he dies; and the final chapter's stream-of-consciousness relation of the rise and fall of the USSR from Lenin's own supine p-o-v. I came to this novel curious about how ideas are sold to people, and the novelistic control of this theme more than rewards the careful reader. Not a long book, this is both its strength and its slight shortcoming. I imagine Kalfus had pared down a longer draft, as there is no unessential material here at all. A lesser novelist would have wandered into fleshing out more characters, following up the fates of Volodov and Astapov with subplots stretching into the future, and would have showed off more of his (or her) knowledge about the time. I'll certainly search out his two earlier volumes of short stories now. As the bibliographical note after the novel indicates, his research matches his fictional talents. He even acknowledges Sheila Fitzpatrick's "unimaginatively titled" Commissariat of Enlightenment--for such an organization did exist, as Fitzpatrick studies. What a title: a group to enforce and rule over indoctrination into "scientific" study of history, laden with documents written by intellectuals for workers to educate the latter about why they were so idolized by the former.With a keen understanding of the, well, dialectics involved in such a Soviet mission, Kalfus deletes, drains, and cuts, like the film editing, the embalming, and the dictate by terror that he intertwines into the three themes of his story. It makes for gripping if not casual reading. I only wish he had allowed more room for following through Astapov's fate after the establishment of Stalin's power. Yes, a whole other novel is buried in a few asides of this one. I wish there was a sequel--Kalfus makes you care about all three of his protagonists, no mean feat when they all turn out to be so terrifying in their respective devotions to their propagandistic crafts.

Visual images as they record, influence, and remake history.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Kolya Gribshin, a young cameraman working for the Pathe Freres Cinematography Company, arrives at the railway station in Astapovo in 1910 to cover the last days of Count Leo Tolstoy, who is dying in the stationmaster's house. Reporters from all over the world have gathered to record his final moments, but only Gribshin is recording the events on film, a new medium. Gribshin knows that printed word is inaccessible to the illiterate masses, but that film can provide immediate "truth" by "ripping away the veil of lies thrown up by language." As we see Gribshin travel between the darkness of the unlit countryside, where he is staying with an illiterate peasant family, and the artificial, arc-lit brightness of the media-mad town, the author uses vivid imagery from black and white photography to show the contrasts between the lives of illiterate peasants living in darkness and concentrating on their next meal, and the lives of an "enlightened" media conveying news to the outside world. Like Gribshin, revolutionaries such as Josef Stalin also recognize the power of the visual image to "educate" illiterate people and shape and control public opinion. Part II takes place nine, war-filled years later, after Russia has faced the horrors of The Great War, the Bolshevik revolution, and the civil war, and Stalin is putting some of these principles into effect through the Commissariat of Enlightenment. Gribshin, now known as Comrade Astapov, is working with him as they attempt to control the masses by controlling visual images--governing theater productions, film projects, and even city planning. Here the imagery of darkness and light, introduced in Part I, becomes a constant motif, as the Commissariat plans to "extend the enlightenment to every remote..village in the tundra," destroying churches and the images (icons) within, if necessary. In 1924, the Commissariat's ultimate image-control occurs when the body of Lenin is preserved "uncorrupted," allowing the state to display publicly a man who never "dies."Kalfus has dared to think big in his debut novel, and his talents are legion. His parallels between black and white photography and his symbols of darkness and light keep the reader constantly aware of the darkness of illiteracy and the light of truth which film can provide. But this is also a cautionary tale about the ability of images to be manipulated and controlled, and all Kalfus's plot elements are subordinated to this single, overwhelming theme. Gribshin, the "lens" through which the reader views events, never really comes alive, and we do not know his motivations or see him wrestling with inner conflicts. He is, ultimately, a cog in the apparatus of the Commissariat of Enlightenment, a vehicle through whom the author advances his theme, not a thinking human. The novel is very tight, however, with no loose ends, and when Kalfus observes that the West, too, is creating an image-ruled empire by presenting so much imagery and meaning that "the sum [beco

An enjoyable novel of ideas.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Kalfus knows his material on Russia, where this story is set. This is part historical fiction--one that takes acknowledged liberties, even distortions--and part novel of ideas. The novel is written in two parts, the first of which deals with Tolstoy's dying days and the media circus and inner-circle infighting that attends this debacle. The second half of the novel takes place in post-revolutionary days and incorporates characters and themes from the first half in a manner that is resonant, even predictable, but not pat. Major themes include: visual culture trumping the written word; the manufacture of "history" through media, including propaganda (the then new medium of film is central); the limitations of science, especially when confronted with the religious impulses/needs actually felt by people. As is often the case with novels of ideas, the characters are rather thin and without much inner life. Action is privileged over motivations. But if you like the ideas, you'll like the novel.

Lies More True Than Truth

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

In the West, the Enlightenment replaced supernatural religious explanations of the world with faith in human reason and science. In the Soviet Union, the Commissariat of Enlightenment replaced Orthodox religion and its icons with faith in the objective historical necessity of socialism and the new icon of Lenin. In the West, our science has ultimately taught us that to measure a thing is to change it; in Soviet propaganda, the film camera's lights were used to distort reality, giving the appearance of truth to lies created in the name of an allegedly greater truth. As Ken Kalfus' protagonist observes, the belief in invariant facts is itself a kind of superstition, giving insufficient credit to man's ability to remake both the past and the present.In the guise of a novel set in the waning days of the Russian Empire and the early days of the Soviet Union, Ken Kalfus has given us a brilliant meditation on the power of images and words, the nature of truth, and the human need for myth and immortality. The book itself illustrates some of his themes -- the characters and scenes are drawn so vividly and persuasively that if you were to ask me a year from now how Lenin died or how he came to be embalmed, I would probably tell you the (inaccurate -- or is it?) story that Kalfus tells. The development of Gribshin/Astapov from a naive and emotionally vulnerable young man into a propagandist so entranced by images that he has lost almost all ability for direct human connection is subtle and seen from the outside, as though observed by (what else?) a camera. This is superb fiction, thought-provoking and entertaining at the same time. Highly recommended.