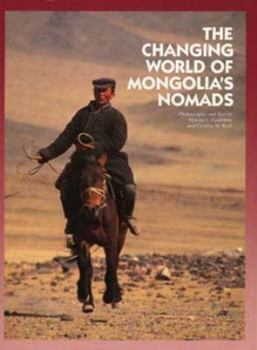

The Changing World of Mongolia's Nomads

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In 1989, renowned anthropologists Melvyn C. Goldstein and Cynthia M. Beall secured permission to conduct anthropological fieldwork in Mongolia. Goldstein and Beall watched as a negdel (herders'... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0520085515

ISBN13:9780520085510

Release Date:February 1994

Publisher:University of California Press

Length:176 Pages

Weight:1.75 lbs.

Dimensions:0.5" x 8.4" x 11.1"

Customer Reviews

2 ratings

Nomads Not Mad about Capitalism

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Some books featuring photographs of faroff places fail to provide even a minimum of explanatory text. It's pix or nothing. Other, academic books, provide great masses of information without any pictures at all. Only a few, it seems to me, try to balance the two features. I must say that this one really hits the nail on the head. That's why I've given it five stars. It is a book full of beautiful photographs of Mongolia's stunning landscapes (and a remote part of the country at that) and the daily life of its nomadic population. But it also provides a very well-written and jargon-free study of why those nomads did not cheer the end of Communism and start of free-market capitalism wholeheartedly. The negdel, or herders' collective, may have been limiting in terms of freedom, but it offered a stable, fairly prosperous existence to people who had known the depths of privation not so long before. When Mongolia became a democracy in 1991, all the trappings of the old Communist system were to be scrapped. But as we know, political freedom does not guarantee economic stability. The nomads living 850 miles from the capital city rightly worried that their living standard might take a dive. It did. They did not take this lying down, however. The former collective leaders began to make deals around the country and with China as well in order to maintain the supply of goods that the nomads had come to expect as part of normal life. The narrative ends in 1993, so we don't know how things have turned out. There's plenty of standard anthropological information about nomad life, along with descriptions of the authors' experience. A very well-organized and presented book. OK, maybe it's short--maybe article length if you take out all the photos---and not academic enough for sticklers, but I found it most useful and interesting. There should be more like this.

Wonderful Insight into Mongolian Culture

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

Melvyn Goldstein and Cynthia M. Beall's anthropological study of a Mongolian herding community, presents an intimate portrait of life on the steppes and the dramatic changes these people have undergone through the previous seventy years of Communism. In the introduction the authors provide a brief overview of Mongolian history from the conquests of the twelfth century khans to the development of the Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party under the Soviet System. While continually emphasizing the nomadic herding economy, Goldstein and Beall's book is really a close look at the lives of individuals and families and how they survive both this harsh climate and the changing political and economic scene.Goldstein and Beall first layout a the problem of survival in the difficult environmental conditions on the steppes and the tenacity, illustrating the point with the tale of a herder found frozen to death as he crawled toward his home, less than a kilometer from safety. It is the livestock, contend the authors, that are the wealth and the security of these nomads. Herds are portable wealth on four legs of which no portion is wasted and each animal fulfills a specific function in the provision of basic needs: food, clothing, transportation. "Climate drives the annual cycle of the nomads life" and determines the survival of both herds and herder. Goldstein and Beall stayed in the herding community of Moost in the Altai Mountains. Particularly detailed descriptions of traditional Mongolian hospitality--the exchange of snuff, the serving of milk-tea and "hospitality" foods--give a warm picture of an extremely outgoing and friendly people. The authors also give detailed descriptions of daily activities: slaughtering a sheep, making cheese, drying milk curds. Most such work is part of a continual preparation for surviving the extreme winters. Even ritual actions demonstrate the difficulty of life on these steppes. Goldstein and Beall attended several hair-cutting ceremonies for Mongolian children. This ritual first haircut does not take place until a child has reached the age of four or five, demonstrating that it is likely to survive childhood. One of the questions the authors had for the Mongols was how their lives had changed under the Communist collectives and how they viewed the new free-market economy. Surprisingly, the answer was generally a noncommittal shrug. When the collective system was first forced upon the Mongols by the Communist government in 1927, herders slaughtered their animals rather than turn them over to government ownership. A less direct approach was taken by the government which, through excessive taxation, forced the independent herders to turn to the collectives for survival in the same way that tribes had traditionally banded together to survive adversity. The collectives, called negdels, took care of the business end of marketing the herds and providing social services. No