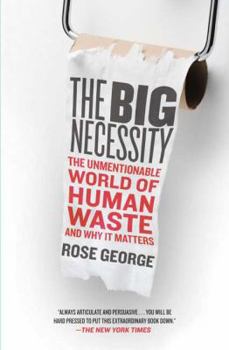

The Big Necessity: The Unmentionable World of Human Waste and Why It Matters

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

"One smart book . . . delving deep into the history and implications of a daily act that dare not speak its name." -- Newsweek Acclaimed as "extraordinary" ( The New York Times ) and "a classic" ( Los Angeles Times ), The Big Necessity is on its way to removing the taboo on bodily waste--something common to all and as natural as breathing. We prefer not to talk about it, but we should--even those of us who take care of our business in pristine, sanitary...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0805090835

ISBN13:9780805090833

Release Date:July 2009

Publisher:Holt McDougal

Length:288 Pages

Weight:0.60 lbs.

Dimensions:0.9" x 5.2" x 8.0"

Related Subjects

Conservation Cultural Earth Sciences Engineering Environmental Science Globalization Nature & Ecology Politics & Government Politics & Social Sciences Science Science & Math Science & Scientists Science & Technology Social Science Social Sciences Social Work Technology Travel Travel WritingCustomer Reviews

4 ratings

Oh, Excetra!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

When I was young and living in very rural farm country and adventuring in the woods or hills and had to take a dump, I did what everyone else did: squatted, made some crap, wiped myself with a few leaves or a handful of grass, and moved on. (If the foregoing language disturbs you, then don't read this book; it's just as graphic, especially in the latter part.) Now, imagine the teeming, close-living tens of millions in the slums and cities of developing countries--and even growing India--where, today, open defecation (that's the "polite" word, which is not that often used in the book) is the socially acceptable and often economically-necessary thing to do. Because it's cheap. There are no sewer systems, few toilets or even working public or private pit latrines. And where does this excreta go--be it India, Africa, China, Tibet, Mexico and even lesser sanitary places? Into the streets, ponds, rivers, oceans and even drinking water. Multi-tons of it everyday. In some African countries, Tanzania and Kenya are two examples, the cheapest latrine is a plastic bag: "defecate, wrap, and throw. Anywhere will do, though roofs are a favorite" (pg. 210). Millions upon millions of people world wide have to make a choice when it comes to ridding themselves of excrement: "contaminating the environment or contaminating human settlement" (pg 222). This book is shocking, but it has to be. Fortunately, in the beginning, the author spares us the worst part of the history (and history-in-the-making) of sanitation by discussing the glories of the sewer systems in Britain and the U.S. Then, she moves to other parts of the world. I began to think to myself, "Why would I want to tourist in certain countries when I could easily step in human feces--yes, it's everywhere (sidewalks, roads, inside public buildings, alleys, et cetera)--and also have no facility to relieve myself? At first, I thought the author must be exaggerating (it can't be THAT bad), but she produces all kinds of evidence: statistics, quotes and her own experiences. Even in the good ole USA, pharmaceuticals can be found in drinking water: meds for heart disease, mental illness, epilepsy, et cetera. These trace amounts deform frogs and fish. The effect on humans? Not yet known. The author makes a strong case for prioritizing the subject of removing and using human waste. But few want to talk about it or spend money on it. Hopefully, her book, and others, will enlighten people (politicians, especially).

This book should be a best-seller

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

As for the organization of this book, I'd give it 3 stars. But the subject matter is so important that this should be a best-seller, on every thinking person's reading list. The book begins with some historic background on sewers, and how sewers and the flush toilet drastically improved public health. I would have enjoyed more of this. There's an overly-long section on high-tech Japanese toilets and why they haven't become popular elsewhere. I would have preferred less of this. I don't want a high-tech toilet, but would be interested in learning more about the composting toilets being used in some places in the Far East and Europe. The real focus of this book, it seems to me, is the LACK of toilets and sewers in so much of the world. It's horrifying how many people still defecate outdoors, mostly because their governments have ignored sanitation, and the effects this has on public health. Billions of people have few options, little knowledge, and no money with which to change the situation. Like other reviewers, I would have appreciated more details about different types of toilets, latrines and the like, how efficient they are (or aren't), etc. The interviews with various activists, especially in India and China, who are working to improve things, are interesting. Despite their tireless efforts, it doesn't sound as if the battle for sanitation is being won. Huge slums everywhere are growing faster than the problems can be addressed. Anyone who has read "Angela's Ashes," and remembers the descriptions of the neighborhood toilets the McCourts used in Ireland, will recognize this. As for those of us in the Western world, it's appalling that so many of our cities still pollute the oceans with our sewage. In other words, this isn't a third world problem, it's a WHOLE WORLD problem. Equally appalling is that supposedly "clean" sewage by-products, heavily contaminated by chemicals, are being used as crop fertilizers in the U.S. and England. Sickening -- literally and figuratively!

An entertaining story of toilets

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Although I have often read in the bathroom, I never thought to read such an interesting and, dare I say it, entertaining book about defecation and waste removal and treatment. All humor aside (and I guess its taboo is why one feels compelled to try to be humorous about this subject), this is actually a very serious subject. The author tells us how the creation of sewage systems, and flush toilets, has probably led to a hugh improvement in life expectancy, since fecal related illness was, and remains in most of the world, the biggest killer (especially of little children, the elderly, and the immuno-compromised). It is astounding to learn that most people don't even have outhouses, but must just squat where they can. The desease ramifications of this simple fact are enormous, and not humorous at all. Suddenly, the reader runs into some very sobering facts. On a personal level, I don't think I'll ever put grease down the sink again, after reading about those (literally) walls of grease in the sewers. Her walk through a sewer amazed me and, for the first time, I realized that the people that do this work routinely are a bit heroic, putting life and limb at risk for our public health. I do recall that when I lived in Louisville, KY years ago, the sewers exploded when a factory emptied some chemical down the drain. This is very dangerous. I recommend this book absolutely.

Open Discussion of a Forbidden Topic

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

What if you learned that a particular problem was causing 80% of the illness in the world and was killing a child every fifteen seconds? Would you want to find out more, and insist that governments and the world do more, to improve the problem? What if you learned that one of the big reasons that governments and the world aren't doing more is that the problem is, well, yucky, and people don't like talking or thinking about it? There are blunter words for the problem, and Rose George uses them; the problem is feces. It is the topic of her book _The Big Necessity: The Unmentionable World of Human Waste_ (Metropolitan Books), a sobering and eye-opening account of just how badly the world handles this one great and inevitable problem. Most of the people who read this book will be among the set that uses flush commodes which connect to sewers and treatment plants, considered the tops in fecal disposal. But 2.6 billion people lack not only toilets, but also lack latrines or outhouses or even a bucket. Toilets and sewage treatments have their problems, covered here, but with billions of people who literally have no place to go, feces wind up all over the place, easily getting into food and water and causing misery. George has been to sewers of huge cities, wandered excrement-coated slum streets, experimented with public toilets in rural china, and visited the workers who clean sewers or empty pits. There is humor here (not much of the toilet variety) and well-crafted explanation and description, but it is not overall a pretty picture. If you don't want to think about this problem, that's just the problem. Toilets, if a culture has them, are only a starting point. In the typical sewage system, the flow is eventually separated into the cleaned liquid effluent which goes back into the water and the solid sludge (more trendily called bio-solids) which is a bit of a problem. It is pretty clean, and naturally would make a good fertilizer, and in the US it does get spread around all over. The problem is that anything goes down our toilets, like unused drugs or heavy metals. Those who worry about the application of such molecules onto our crops are not comforted by the Environmental Protection Agency which says such application is safe. A great deal of George's book is not about people with toilets and sewers. In India, the lowest of the class still held to be Untouchables get an income by collecting feces deposited on the open ground. There are flying toilets or helicopter toilets in Kenya and Tanzania. It's a nice way of describing a disgusting practice: defecate into a plastic bag, then fling the bag to a rooftop or into the alley. George cites the Chinese as being especially innovative and open about sanitation; feces have always gone onto the fields there, but more recently homes have been equipped with biogas digesters providing methane that heats homes and stoves. There are still urban problems, but the government knows how important