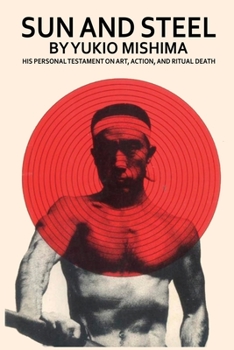

Sun and Steel

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In this fascinating document, one of Japan's best known-and controversial-writers created what might be termed a new literary form. It is new because it combines elements of many existing types of writing, yet in the end fits into none of them.

At one level, it may be read as an account of how a puny, bookish boy discovered the importance of his own physical being; the "sun and steel" of the title are themselves symbols respectively of the cult of the open air and the weights used in bodybuilding. At another level, it is a discussion by a major novelist of the relation between action and art, and his own highly polished art in particular. More personally, it is an account of one individual's search for identity and self-integration. Or again, the work could be seen as a demonstration of how an intensely individual preoccupation can be developed into a profound philosophy of life.

All these elements are woven together by Mishima's complex yet polished and supple style. The confession and the self-analysis, the philosophy and the poetry combine in the end to create something that is in itself perfect and self-sufficient. It is a piece of literature that is as carefully fashioned as Mishima's novels, and at the same time provides an indispensable key to the understanding of them as art.

The road Mishima took to salvation is a highly personal one. Yet here, ultimately, one detects the unmistakable tones of a self transcending the particular and attaining to a poetic vision of the universal. The book is therefore a moving document, and is highly significant as a pointer to the future development of one of the most interesting novelists of modern times.

Related Subjects

Beauty Honor Identity Japanese Culture Masculinity Motivation Autobiography Memoir Arts & Literature Authors