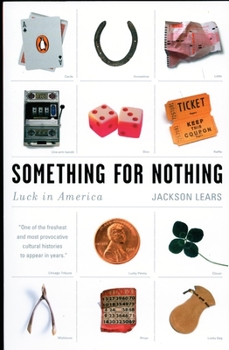

Something for Nothing: Luck in America

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Jackson Lears has won accolades for his skill in identifying the rich and unexpected layers of meaning beneath the familiar and mundane in our lives. Now, he challenges the conventional wisdom that the Protestant ethic of perseverance, industry, and disciplined achievement is what made America great. Turning to the deep, seldom acknowledged reverence for luck that runs through our entire history from colonial times to the early twenty-first century,...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0142003875

ISBN13:9780142003879

Release Date:July 2004

Publisher:Penguin Books

Length:416 Pages

Weight:0.88 lbs.

Dimensions:0.9" x 5.6" x 8.5"

Customer Reviews

3 ratings

The analysis of luck

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

It is patently obvious that Americans have always been a gambling people. But in Something for Nothing, Jackson Lears takes a further analytical leap, looking at how the "culture of chance" has been central to American life and thought. Though In Lears' summation the self-made man has been more influential than the confidence man in American, an America shorn of hereditary privilege and deference to one's betters was a fruitful breeding ground for the legions of Americans-from land speculators to day traders-seeking something for nothing. Lears takes an interesting approach, admitting at the beginning that he is not writing a history of gambling but of chance, which he sees as a sort of anti-virtue, a shortcut to grace for those not willing to put in long hours at the hard work of self-betterment. Lears sees an Apollonian/Hermetic dialectic throughout much of Western culture, with the trickster Hermes, patron of the lucky rounder, pitted against the rationalist Apollo. The rampant gambling found in most periods of American history is symptomatic of a deeper struggle within the American psyche between chance and control. Along the way, Lears hits all of the signature spots of any gambling history: Dostoyevsky's manic Roulettenberg, Jamestown settlers "bowling in the streets" while starving, itinerant blacklegs like Canada Bill Jones and George Devol, and many more. But he ties these evergreens to a larger cultural force that also shaped the sermons of Jonathan Edwards, the philosophy of William James, the writing of Ralph Ellison, and the music of John Cage. Lears also pulls in an impressive mass of cross-cultural analysis of luck and chance as a means to break down the components of the American culture of chance into its European, African, and Native American components. The wild nut diviners of Ghana, white and black American bibliomantics (those who used the Bible for divinatory purposes), and the Runyonesque craps shooter fingering a lucky rabbit's foot are equal parts of the same culture of lucky superstition. One of the real strengths of Something for Nothing is that it democratizes luck-trailer park denizens at Tuesday night bingo have an equal place at the table with Marcel Proust. An America where gambling in its many manifestations is an increasingly powerful revenue producer and job provider needs such an honest look at the culture of chance. There is undoubtedly a reason why many Americans choose casinos over tax increases most of the time, and Lears comes as close as any historian to understanding why. According to him, there is a fundamental tension throughout much of American life between the managers and those entranced by accident and chance. Though Lears focuses more on this struggle in letters and ideas, it is easy to see how the struggle for control seeped from the boardrooms and workfloors of America into popular culture and life. Gamblers like Titanic Thompson and aleatory artists like Joseph Cornell stand out as cultural

Something Special

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

In "Something For Nothing" Jackson Lears has come up with nothing less than a fresh way to look at the American idea. He tells the story of two cultures: -- "the culture of control," and the "culture of chance" -- that have bubbled beneath the surface American life from the beginning (and he traces their roots deeper into history as well). He returns to gambling often, but this is much more than a social history of gambling. It's easy to think of America as place where the culture of control dominates and always has, in the form of the "work ethic" that says that the way to get ahead is to work hard, merit will be rewarded, etc. This notion is so basic to the way many contemporary debates are framed that we hardly even think about it anymore. But there are now and always have been competing ideas out there -- in the most unexpected places -- about the role of chance, or luck, in life. At times the culture of control has simply denied chance, and aother times it has tried to subdue it (through everything from insurance to statistics-based social science to management theory). At times the lines have been blurry -- business risk-taking has been culturally rewarded even when it is as much a matter of chance as a (demonized) spin of the roulette wheel. Obviously I'm oversimplifying, but the book is incredibly thought-provoking. It's also thick with references drawn from history, culture, art, literature, philosophy -- at times this is dazzling and at times it's overwhelming; one almost feels the need to pause, get a Ph.D. in American Studies, and then return to the book. But on the whole Lears is in command of the material, and makes his book a fascinating and important read.

Gambling for Grace

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

This is the third book by Jackson Lears and it confirms his status as one of the most innovative of American intellectual historians. Like his previous books "No Place of Grace" about late 19th century conservative intellectuals, and "Fables of Abundance" about American advertising, his approach is idiosyncratic, and not easily summarized. His work uses a large amount of literary allusion, so as "Fables" invoked Little Nemo and examined Henry James and Joseph Cornell, in "Something" Cornell makes a return appearance, along with Mark Twain, Damon Runyon (of course) and a special examination of "Invisible Man."Lears' book is based on a contrast between a "Culture of Chance" and a "Culture of Control." Naturally, the growth of science has helped to vastly strengthen the latter against the former. But it is not that simple. There is a clash between differing Christian, indeed Protestant, views of grace. Is grace granted unconditionally, freely, like the winner of a game of chance? Or is it a matter of Divine Providence which, if not saying salvation is earned by merit, does strongly state that the hard working self made man either will get success or deserves the success he gets. Lears discusses this in a nuanced and subtle reading of the theologian Paul Tillich. One the one hand he was promiscuous and power-hungry ("not an attractive combination, in a theologian or anyone else") and his view of grace could be fashionable, dangerously naive and convenient. But there was something important, that recognized the link between grace and chance. "...Tillich had recaptured a key element in the religion of Jesus..." It is at this point that one must demur. As a Jew, and as a critical historian I must object to any view that attributes to Jesus the ideas of grace that were developed by Paul, Augustine, Luther, Calvin or by American theologians. If there is one constant flaw of American Protestantism, both liberal and conservative, whether evangelically Orthodox or Mormon/Jehovah's Witness heterodox, it is to attribute to first century Palestine beliefs which could only have developed in the United States. Although more sophisticated than most, Lears (and the late Christopher Lasch) fall to this temptation. Another problem is that Lears does not discuss the flip side of grace. Damnation can also be awarded freely, and with no right of appeal. And if most Protestants believe they will be saved, for much of the first few centuries of Protestantism its theologians assumed most of their fellow Christians were doomed, while the non-Christian majority of humanity did not have a chance. To the extent that American Protestants no longer believe this, it is not simply the result of glib positivism, complacent pro-capitalism or sinister and sentimental "therapeutic" motifs."Something" is also weaker than "Fables" because it is often repetitive and less coherent. Nevertheless there is much of value for the reader here. He discusses the culture of c