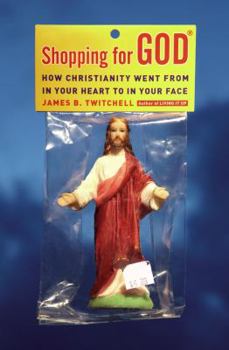

Shopping for God: How Christianity Went from in Your Heart to in Your Face

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Not so long ago religion was a personal matter that was seldom discussed in public. No longer. Today religion is everywhere, from books to movies to television to the internet-to say nothing about politics. Now religion is marketed and advertised like any other product or service. How did this happen? And what does it mean for religion and for our culture? Just as we shop for goods and services, we shop for church. A couple of generations ago Americans...

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0743292871

ISBN13:9780743292870

Release Date:September 2007

Publisher:Simon & Schuster

Length:324 Pages

Weight:1.35 lbs.

Dimensions:1.2" x 6.4" x 9.5"

Customer Reviews

3 ratings

A "Cold" Christian and Professor of Advertising Coolly Addresses "Hot" and Growing Churches

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

James Twitchell's "Shopping for God" is about how many modern-day Christians in America go about the process of consuming - buying and selling - the religious experience. Twitchell focuses on what has been happening in America where there is a free market in religious products, more commonly called beliefs and on what is common with fast growing denominations - selling. Today, a church is chosen, and "purchased" in an act that mimics consumption elsewhere. Instead of expecting people to accept their practices, fast growing denominations have tailored their churches to meet the needs and desires of those they hope to serve. They define the church in a much more expansive way than traditional churches do. They attract people from a variety of religious backgrounds and center their preaching on the problems of daily life - the pain and problems that stem from a broken marriage financial trouble, aging, aloneness, substance abuse, etc. Attendees seek relief, as opposed to guilt; they want good news, not more bad news. Essentially, this about how churches get you and others into church? How are the sensations of these beliefs generated, marketed, and consumed? Who pays? How much? And how come the markets are so roiled up right now in the United States? Or have they always been that way? Does the church on the corner operate like a gas station? What about the mega-church out thereby the interstate - is it like a big-box store? What about the denominations that they represent - do they compete? Why are they hiring so many marketing consultants? How do churches position themselves? How do they separate themselves from one another? How they break through the clutter of not just other religions but other denominations? Author Twitchell, a professor of English and Advertising at the University of Florida, considers himself a cold Christian - a disinclination to care all that much about his own religion and an even stronger disinclination to care about other religions - and writes from this point-of-view. While some will be put off by "Selling" (it does not draw on empirical data), it is a good read and should generate discussion on several important observations Twitchell makes.

Selling an Experience: The Dirty Details

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Twitchell's book is part history, part analysis of our present situation. He uses a lot of examples from the course of the church's history to show different ways in which the church has tried to market itself. Of course, he notes that for most of its 2000-year existence, it hasn't really felt the need to compete as it was the only show in town. Still, he details the Catholic church's sale of indulgences and icons that led up to the Reformation, and notes that these sales were primarily sales of an experience. If people wanted to experience grace and forgiveness; to experience some kind of emotional high, this was how they could purchase it. Twitchell also spends some time with more recent trends as he details his theory of selling an experience. He especially details the techniques of revivalist Charles Finney, who would purposefully seat his most exhuberant audience members up front (the "anxious bench") so that others would see them and be caught up in the moment. This was a technique that exploited herd mentality and emotionalism, but also employed the technique of urgency: implying that you don't want be the last to convert; that it's for a limited time only. All of these techniques, Twitchell argues, are used by many churches all over. Twitchell spends a lot of time talking about church "branding." Essentially, he says, churches are trying to sell a story and an experience and less the message of salvation. That comes later, but first the experience has to rope people in and give people a sense that this experience is better than the experience they'll get elsewhere. Similar to Finney's revival tactics, Twitchell argues, people will first look for how good a particular church makes them feel. Is the congregation welcoming enough? Is the music moving enough? Is the sermon passionate enough? That, he notes, is what branding is. He makes lots of comparisons to other products: you have a choice of half a dozen dish soaps and they're all essentially the same...it's the brand that people are buying, not the product itself. So when churches try to "brand" themselves, they're trying to differentiate themselves from others. So they come up with slogans, they may emphasize how welcoming they are or how exciting they are, they may talk about how they aren't your father's church or that they're church for people who don't like church, and always with subtle or overt digs at other churches. Most of these churches are pretty much the same, he argues, so they need to emphasize their brand over others. No one escapes scrutiny in this book. Twitchell analyzes the megachurch's mastery of being the Church That Feels Good and being the big box church that offers what the small Mom and Pop church can't. And in a bit of commentary on post-denominationalism, Twitchell notes that megachurches provide the "generic brand" of church. When people feel less of a tie to a brand (Methodism, Lutheranism, etc.), they'll "trade down" to the product that works just as w

Straight from the apatheist's mouth: the marketing of religion in America

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

"This is not a book about God" (p. 1). Thus begins James Twitchell's book, Shopping for God. "Essentially, this book is about how religious sensation is currently being manufactured, packaged, shipped out, and consumed" (p. 3). It is about "... buying and selling..." the religious experience. "...[We] are doing a robust business in supplying valuable religious experiences for shoppers at reasonable prices" (p. 2). Sam Harris and others might counter that this price is too high, but that's a subject that can reviewed in their books. Twitchell uses a lot of examples in this well-written book. He brings up the evolution of the religious braggart in the entertainment industries (note Mel Gibson's impact with The Passion of the Christ). He discusses the development of the Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson types (did Robertson really state of liberal professors, "They are racists, murderers, sexual deviants, and supporters of Al Qaeda -- and they could be teaching your kids" (p. 8)). Radio, television, books, and the internet... these are all fertile ground for the planting of of the seeds of religious dogma. "Just about every American -- 96 percent, in one poll -- believes in God" (p. 22). Twitchell proclaims that there are over 2000 religious groups in America today. And there is extreme competition for market share. People are shopping, and religions are branding. Twitchell discusses the marketing strategies in this Church Growth Movement. There is competition for your soul. Here's an example that I missed: the United Church of Christ's infamous "bouncer" campaign in 2005. The television ad goes like this. All types of people are denied entry to a church by a tough bouncer. Fade to black. The a narrator states "Jesus didn't turn away people. Neither do we" (p. 160). Mormons, Lutherans, Baptists, Episcopalians -- even Unitarian Universalists (the Uncommon Denomination... we're here if you need us, but we're not going after you) -- they all have marketing campaigns. This evolution of marketing programs has led to the development of Megachurches. Twitchell discusses these, and their growth, in some detail. Twitchell concludes, "How religion allows us to make either meaning or mincemeat out of this shrinking world remains to be seen" (p. 291). Apatheist -- that's what Twitchell calls himself ("... a disinclination to care all that much about one's religion and an even stronger disinclination to care about other people's" (p. 33)). This was an interesting, not so flattering, overview of the religious world we live in in America. We line up to belong. I have no idea whether people pretend to believe, try to believe, or truly believe. Twitchell just argues that it seems like every time you turn around, someone is throwing it in your face. And nobody seems to be complaining. As Rod Serling might say, ""There is nothing wrong with your television set..." Our minds are not our own.