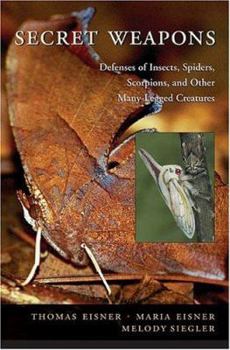

Secret Weapons: Defenses of Insects, Spiders, Scorpions, and Other Many-Legged Creatures

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Mostly tiny, infinitely delicate, and short-lived, insects and their relatives - arthropods - nonetheless outnumber all their fellow creatures on earth. How lowly arthropods achieved this unlikely pre-eminence is a story deftly and colourfully told in this follow-up to the award-winning For Love of Insects. Part handbook, part field guide, part photo album, Secret Weapons chronicles the diverse and often astonishing defensive strategies that have...

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0674018826

ISBN13:9780674018822

Release Date:November 2005

Publisher:Belknap Press

Length:372 Pages

Weight:1.86 lbs.

Dimensions:1.1" x 6.3" x 9.2"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Nice style and content

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

This book is written in a concise, synoptic manner. This is a very effective style for presentation of the diverse subject matter in this book, and I would like to see it used elsewhere. It greatly simplifies the assimilation of essential information. In my opinion there is no better introduction to the wide scope of innovations related to arthropod defense, and chemical defense in particular. The Eisners are to be commended to make this information, previously available only through the review of a large number of separate scientific publications, so readily accessible to the public. This book is as useful to the scientist as it is to the young student of nature. Remarkable!

One of a kind

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Plot: How bugs defend themselves Pros: Really, really interesting. Lots of color pictures. One of a kind work. Cons: Lots of big words and chemistry stuff I have forgotten. Other Thoughts: Bugs are neat. Many of them taste bad to predators, sometimes they sting you, or bite you, or have venom. Ants seem really annoying (even to other bugs). Reminds me why science is cool as some insects have neatfully (a new fake word!) ingenious adaptations. Grade: A

Beautiful Photo-log and Chemical-Defense Attributes of Insects

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

This book has beautiful color photos (note the front cover for an example) of a good array of mostly North America insects along with their taxonomic order and common names and with brief explanations of their ecology and specific defense mechanisms coupled with detailed chemical analysis. The book finishes with photos and explanations of essential insect collecting gear and lab analysis equipment. Over-all, I was struck with the incredible dynamics of insect defenses and how researchers are finding ways to harness these chemicals for a host of products such as medicines, bug repellents, plant defenses, etc. Medical researchers, biochemists and laymen alike, should find this information most helpful and interesting.

Lavishly illustrated; thoroughly professional

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

The "weapons" in the title are mostly chemical. They are poisons that insects and their kin use to protect themselves from predators. Spiders, insects, snakes and other animals use poisons to subdue their victims as part of their preying arsenal, but what the authors focus on in this unusual book are chemicals used by "many-legged creatures" as defensive weapons. Pick up certain beetles or fly larvae or especially some grasshoppers and caterpillars and they will vomit noxious stuff on you. It will smell bad, it may contain harmful bacteria, and it will be "spiked" with deterrent chemicals stemming from plants eaten by the insect. Or the insect may defecate on you. Imagine that you are the size of the insect, one of its predators. Imagine the effect of copious amounts of feces coming at you. The authors show how these defenses actually work on predators like wolf spiders and even small rodents. I was especially struck by how often these defenses apparently evolved as defenses against ants. Of course many insects spit, spray, sting, and bite in response to being disturb or threatened. This is how they deliver their noxious chemicals, their poisons, their foul-smelling stuff, their stuff that stings, debilitates and even kills. Eisner, Eisner and Siegler give numerous disquieting examples of exactly how this is done in 69 very creepy chapters. Each chapter is dedicated to a particular creature or Family of creatures from vinegaroons (Chapter 1) through bombardier beetles (Chapter 35) to the honey bee (Chapter 69). Millipedes, cockroaches, ants, aphids, termites and many others make their gruesome appearance. Gruesome...? Well, it's all in the eye of the beholder, I suppose. The many photos of the creatures that accompany the text are arguably beautiful. With some detachment I can see the earwig (Doru taeniatum) shown in all its black and brown and tan glory on page 77 as quite attractive. (However the beauty of the photo of the cockroach with its egg case hanging out the back on page 59 is a bit beyond my ability to fully appreciate.) Nonetheless I realize that people who collect and study insects do find them attractive, and properly seen they are as beautiful as...well, Penelope Cruz. Insects are marvelous beings with the most amazing talents, their abilities well beyond that of modern science to emulate. Would that we could build robots with the ability of the ant! Still I must say that for many readers this book could prove an unsettling experience. But in truth the photos are amazing. They are brilliantly colored and sharply focused, showing the creatures in various poses, eating, mating, being eaten, fighting, secreting, guarding eggs, etc. And there are some very nice shots taken through microscopes that reveal wondrous detail. Clearly "Secret Weapons" is a book for enthusiasts and professionals. Not only are the scientific names given for each creature along with the common names, the authors also give schematic d

The Wars of the Multilegged

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Even if you live in the city, you probably encounter insects or spiders every day. Such animals are enormously successful almost anywhere you go, except for marine environments. There are many reasons for their success, but in _Secret Weapons: Defenses of Insects, Spiders, Scorpions, and Other Many-Legged Creatures_ (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press), the concentration is on defensive strategies, diverse and strange. The authors, Thomas Eisner, Maria Eisner, and Melody Siegler, are biologists with a mission, to show largely in photographs some of the defenses, especially chemicals but also mechanical measures, mimicry, camouflage, and warning colors. The authors say this is the first photographic introduction to the defenses of arthropods, and it is a book of wonders. It consists of 69 short chapters, each featuring one arthropod and concentrating on a particular method of defense. There are "sprays, oozes, sticky coatings, ... enteric fluids, feces, or systemic toxins." Some insects produce their chemical defenses as part of their physiology, but others grab toxins from the outside and eat them or smear them on themselves to get protection. The toxic or irritant chemicals are shown here in diagram form. The degree of sophistication of defenses among these most humble of creatures must incite any reader's admiration. There is one surprising tactic after another on these pages. It is amazing, for instance, that any creature is able to use hydrogen cyanide as a weapon; cyanide is an almost universal poison, blocking the chemical cycles of oxidation. Soil centipedes, however, have pores along the body that secrete a sticky substance with cyanide in it. The cyanide forms outside the centipede's body where precursor molecules meet after being ejected. There is a picture shown of a centipede maternally guarding her eggs, ready to launch a cyanide attack on any ant or spider of which they are the natural prey. Acetic acid is familiar as the sour flavor in vinegar. The arachnid named the "vinegaroon" is so called due to the acetic acid in its spray. Vinegar has only a few percent acetic acid, and the vinegaroon's spray has 84%, the highest concentration in nature. Not all the defenses here are chemical; some are mechanical. The bristle millipede looks like a bottle brush. The tufts at the rear of the millipede are actually bunches of hairs with tiny grappling hooks on them. If an ant attacks the millipede, it touches a tuft to the ant, and the hooks attach to hairs on the ant's body. There are barbs on the shaft of the hook as well, and so the millipede's hairs interconnect, immobilizing the ant in a network of locked hairs; when the ant tries to clean itself, it only gets more tangled. Green lacewings lay their eggs on stalks to protect them, and on the stalk leave droplets of oil that repel ants. Once the egg hatches, however, the larva itself can ingest the oil on the way down. Lubber grasshoppers vomit copiously