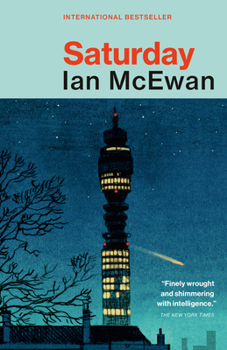

Saturday

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

"Dazzling. . . . Profound and urgent" --Observer "A book of great maturity, beautifully alive to the fragility of happiness and all forms of violence. . . . Everyone should read Saturday" --Financial Times Saturday, February 15, 2003. Henry Perowne, a successful neurosurgeon, stands at his bedroom window before dawn and watches a plane--ablaze with fire like a meteor--arcing across the...

Related Subjects

Contemporary Family Saga Fiction Genre Fiction Historical Literary Literature & FictionCustomer Reviews

I Don't Understand the Good Reviews

Complex, nuanced story told with true mastery of the writer's craft. I loved it!

Up and Dressed in 62 Pages

a gentle, enchanting piece of work

The challenge of the professional reductionist

A study of "the powerful currents...that alter fates."

Saturday Mentions in Our Blog

I recently came across a travel website that proclaimed, “London has a rich literary tradition that permeates its streets.”

It’s true, of course. I know the first time I saw London’s cobblestone back streets, I immediately pictured Oliver Twist and the Artful Dodger tearing through the crowds, possibly having just picked someone’s pocket. For my money, Dickens’ vivid descriptions of 1830s London are just as compelling as his characters.