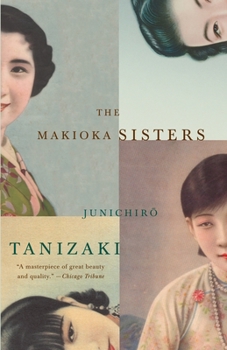

The Makioka Sisters

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Junichiro Tanizaki's magisterial evocation of a proud Osaka family in decline during the years immediately before World War II is arguably the greatest Japanese novel of the twentieth century and a classic of international literature. Tsuruko, the eldest sister of the once-wealthy Makioka family, clings obstinately to the prestige of her family name even as her husband prepares to move their household to Tokyo, where that name means nothing. Sachiko...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0679761640

ISBN13:9780679761648

Release Date:September 1995

Publisher:Vintage

Length:544 Pages

Weight:0.94 lbs.

Dimensions:0.9" x 5.3" x 8.0"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

The world in a grain of sand

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

The Makioka Sisters (Sasame Yuki, Light Snow), first published in 1948, was written by Junichiro Tanizaki (1886-1965). Tanizaki wrote The Makioka Sisters after translating the Tale of Genji into modern Japanese and the Murasaki novel is said to have influenced his own. It tells of the declining years of the once powerful Makioka family and their last descendants, four sisters. It has been translated by Edward G. Seidensticker in 1957. Powerfully realistic, it mourns the passing of greatness while celebrating in wonderfully evocative detail the beauty of a particular time and place, Osaka in the 1930s. In its creation of beauty out of sadness it can be compared to another family saga, The Maias (1888), by the Portuguese master Eça de Queiroz (1845-1900). Why is this long book, largely concerned with trivial family procedures, one of the finest novels written? It is not concerned with great events, causes or philosophies. It has little concern with the war Japan was fighting with China, and then the USA, when the book was first published. Indeed its characters don't think about the war, and in a positive way, which doesn't trivialise their concerns at all (most people in fact don't think about the reasons for a war: perhaps it's better that way). This doesn't mean the book is escapist or superficial, just as the concern with women's lifestyle, dress, makeup, etiquette or social vanity make it something written just for women (books and films were once made - by men - to capitalise on what were considered women's 'little' concerns). Tanizaki does that wonderful thing a great artist can do, he finds the universal in the most exact examination of the particular, and makes a work of relevance to us all. Read another family saga, The Brothers Karamazov (1880) and my candidate for the greatest novel yet written (though I'm more than cynical about the word 'great') and marvel at the many routes artists find to the universal. My review is impossibly partial: The Makioka Sisters is the most beautiful novel I've ever read. The language (translation) is so smooth and flowing, the characters and situations so gentle and muted, yet precise and meaningful, that reading the book is like seeing the universe in a drop of water - you see, which is moving, and awareness of where and how you see brings amazement and then a real pleasure. In this beautiful book the characters have a greater degree of reality than many real people - Tanizaki is a great master of characterisation. I know more about them than I do about most of the people I know. It is done by the accumulation of enormous amounts of detail, but detail which, trivial though it may appear, is just right. The result is the creation of a most ethereal and delicate beauty, a lovely world crumbling to extinction yet all the more precious because of its inevitable passing away. Sachiko, the second sister and her husband Teinosuke are that rare achievement, a convincing depiction of really good and admirabl

Revisiting Tanizaki's greatest novel.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

The first time I read The Makioka Sisters, I called it "fragile and lovely." Recently, I read it again. It's not really fragile and lovely. Actually, it's very matter-of-fact. The narrative mostly recounts events and the characters' reactions to the events. There isn't much description or imagery, like in Kawabata. Even big events like the Osaka flood are recounted straightforwardly, with precision instead of lyricism. But the book is very perceptive about its characters. Tanizaki knew everything about the social class of the Makioka family. The book is full of countless trivial little details about their daily habits, mannerisms, styles of dress and conversations. For example, during one of the family's attempts to marry off the third sister Yukiko, the prospective husband is concerned that she seems moody, and the whole family tries to dissuade him in writing and on the phone. Tanizaki perfectly captures the frantic, businesslike quality of the negotiations, simply by describing their arguments at length. He is so perfectly attuned to the routine of a family of this class that, just by describing it, he can recreate a whole period of history. And his extensive knowledge of small details also makes the narrative very lively, and often funny. The book moves slowly, but I found it addictively readable, both the first time and now. The book is much more than a period piece. It captures the superficiality and transience of a sense of closeness between people. The four Makioka sisters are surely very close to one another. They've been together since they were little, and they get along very well. The three younger sisters live under the same roof until they're all well over thirty. Basically they're each other's closest friends. And yet, the second sister Sachiko has no idea whatsoever about what goes on in her youngest sister Taeko's life. She spends much of the book misinterpreting Taeko's motivations. Taeko also remains friendly towards Sachiko throughout the book, which of course does not in any way prevent her from telling Sachiko nothing of her inner thoughts. Similarly, Sachiko has a very good husband, by any standard. He's very capable, treats his wife well, agrees to support her sisters even though there's really no good reason why he should do so, and engages in self-sacrifice when the situation calls for it. Sachiko should be very close to him, and their marriage is overall harmonious. But their relations are "comfortable" more than they are "close." Sachiko is closer to her younger sisters than to her husband, and we already know the real value of that. The oldest sister Tsuruko grows particularly estranged from the others, since she lives separately from them and also has the formal duty of managing the family. Possibly the most touching moment in the book is a tiny episode in which Sachiko visits Tokyo and goes to the Kabuki without inviting Tsuruko to come along. And Yukiko is the most "traditional" of the sisters, but she's not pa

A great classic.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Tanizaki set out, during the war years, to write a book like The Tale of Genji, in tribute to what was best about the Japanese past. The amazing thing is, that he succeeded. He was able to transfer the spirit of the Japanese masterpiece (which is also a world masterpiece) in modern times and delicately describe a whole civilization which had really been destroyed, even before the war was lost, in the dreadful militarism that caused the war in the first place. This book is beautifully written. As other readers have noted, it does go slowly. So does War and Peace. So do a lot of the other novels that really make you think about life, and love and important issues. The book echoes the leisurely pace of the Makiokas' lives and is very nostalgic--but it is realistic too and does not depict the old society as perfect. Each sister has her own, fascinating character. They do not easily fit into stereotypes. Particularly interesting to me is the character of Taeko, the youngest 'modern' sister who will not (or cannot) behave like her more decorous sister Yukiko, the perfect 'traditional' Japanese woman--who can't get married. Taeko behaves very badly by the standards of her time--and very normally by our standards today. It is interesting to see the tension, and the ways in which her behavior affects everybody around her. Not only are the sisters interesting, but there are many very wonderfully drawn secondary characters, like Saeko's cultured husband, and the foreigners, the Russians, the German family with the two children--Just as interesting as the people though are the customs and the culture. There's cherry-blossom viewing, and a firefly hunt and descriptions of how to wear kimonos and many very wonderful descriptions of Taeko's traditional dance-- It's all a whole different mindset than the way we live today. Really civilized. And yet, at the same time, the Japanese army is committing the horrific atrocities in Nanking-- I would read this first, and then Genji, if you haven't done that (you'll really go back to another time). Also best, I think, in the Seidensticker translation.Someone who likes this will probably also really like In the Shade of Spring Leaves, a translation of the stories of Higuchi Ichiyo, along with a biography of a fascinating woman who died way too young.

Slow and compelling

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Others have commented that this book is slow-going, which I can understand--there certainly isn't a great deal of what you'd call 'action,' in a Hollywood sense--but on the other hand, I found it an amazingly effortless read; pages would simply melt away at an astonishing rate. It's very much a novel after the manner of the nineteenth-century (though it's probably best to avoid Jane Austen comparisons, which, though superficially appealing, ultimately don't really work very well): no modernist jiggery pokery (not that I have anything against that, necessarily), just a straightforward narrative of things that happen. One sometimes forgets how effective this can be, when done well. All this notwithstanding, perhaps the most interesting thing about the novel is its ambiguity: out of the three sisters (the fourth, Tsuruko, being a very minor character, although this does also apply to her, to an extent), only one, Sachiko (the novel's de facto protagonist, I suppose), is made entirely psychologically comprehensible by Tanizaki. Taeko and Yukiko remain to a large extent mysterious throughout. I find that the glib characterizations of them and other major characters in the Vintage edition to be very misleading: nobody in the book can be so easily characterized. Even Taeko's old flame Okubata, who the reader is likely to quickly write off as 'total jerk,' is ultimately given the benefit of the doubt.One thing that may seem strange to some readers is the way that world events of the time are understated. The novel takes place in the years leading up to World War II, concluding at the end of 1940. However, in spite of occasional references to Hitler and "the China Incident," there is little effect on the lives of the Makiokas, and insofar as they are aware of these things, they remain undemonstratively, naturally, loyal to their country and their allies. This, of course, is nothing more than self-evidently realistic, and I certainly hope nobody would be deranged enough to condemn them for it. People have to live their lives; it's not as if the US hasn't been involved in its share of ignoble wars (hmm...can we think of a current example?). Tankizaki may be subtly critiquing this behavior, but it never becomes more than an undercurrent.At ANY rate! This is nothing like my preconception of what Japanese novels are supposed to be like was, based on reading Mishima and Kawabata. It is, however, excellent in its own right. If you want something a little more circumspect than your average novel (whatever THAT beast would like!), go for it.

A sensational story told in beautiful, delicate detail

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 25 years ago

THE MAKIOKA SISTERS tells the story of the lives and relationships of four sisters in the late 1930's and early 1940's in Osaka, Japan. Tsuruko, the oldest, who is married, acts as the head of the household by nature of her age. Sachiko, the second oldest, also married, is a sensitive and intelligent woman who watches over her younger sisters. Yukiko, unmarried, is extrmeley shy and reserved, and extremely dependent upon Sachiko. The youngest, also unmarried, is Taeko (nicknamed Koi-san), a free spirit who finds that she must break with tradition to be happy. It is the responsibility of Sachiko and her husband Teinosuke to find a suitable husband for Yukiko, who must marry before Taeko as custom dictates.The book takes us through several years in the lives of the Makioka family (curiously, since there were only daughters and no sons, both sisters' husbands took the name Makioka), as they experience the joys and disillusions of life in an extremely close-knit family. As their wealth and prosperity wane, they realize that you sometimes must make sacrifices.It was wonderful to read this book knowing that not only was it written by a native Japanese, but that it was also written in that time period, in the early 1940's. Knowing that every description and every conversation was authentic made this an amazing book.I would highly reccomend this to anyone who has an interest in Japanese customs, society and way of life. It was fascinating.