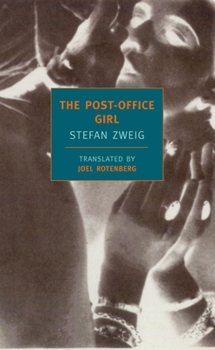

The Post-Office Girl

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Wes Anderson on Stefan Zweig: "I had never heard of Zweig...when I just more or less by chance bought a copy of Beware of Pity. I loved this first book. I also read the The Post-Office Girl. The Grand Budapest Hotel has elements that were sort of stolen from both these books. Two characters in our story are vaguely meant to represent Zweig himself -- our "Author" character, played by Tom Wilkinson, and...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:1590172620

ISBN13:9781590172629

Release Date:April 2008

Publisher:New York Review of Books

Length:272 Pages

Weight:0.65 lbs.

Dimensions:0.6" x 5.1" x 8.0"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

`Names have a mysterious transforming power.'

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

This novel tells the story of Christine Hoflehner, a post office clerk, in a small village outside Vienna some years after World War One. Here Christine exists, sharing a dank attic with her ill mother. The war has stolen her father, her brother and her capacity to laugh. The war may have ended, but poverty has not: `Now it's creeping back out, hollow-eyed, broad-muzzled, hungry and bold, and eating what's left in the gutters of the war.' Christine is roused from this existence by a telegram from her rich aunt, inviting her to a resort in the Swiss Alps. And here, she discovers life rather than existence. Alas, it cannot last, at least not in this form. It's the telling of the story, by the impersonal narrator, that caught and then held fast my attention. Whatever other messages the reader takes from this story, it is impossible to ignore the tragedy and loss as a world shudders in response to one war, in a period which we 21st century readers know will soon be followed by another. It's a combination of this knowledge, Mr Zweig's prose, and speculation about his intentions in writing it but not seeking its publication that make this story so moving. `Someone who's on top of the world isn't much of an observer: happy people are poor psychologists.' Stefan Zweig wrote this novel in the aftermath of World War One, but it was not published in his lifetime. It was first published in Germany in 1982 and was published in English in 2008. Zweig committed suicide in a pact with his second wife in Brazil in 1942. Jennifer Cameron-Smith

Now on my list of favorite books

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

I only review a fraction of the number of books I read, so I don't give this compliment lightly. Summary, no spoilers: Let me start off by saying that it is difficult to give a good review of this book without slight spoilers - but I will do my best and try to still give a flavor of what makes this such a memorable read. This *gorgeously* written novel starts off with a brilliant description of a desolate country post office in Austria, in 1926. Working in this depressing bureaucratic hell, is a 28 year old woman named Christine, who has been beaten down by poverty, dullness and tedium in her life. Christine had a much different childhood; her family had substantial means and lived comfortably, and she grew up a happy and content child. But all changed with the Great War, and they, like so many other Europeans, lost everything. All that remains to Christine is her job with the post office, and taking care of her sick mother in a depressing and decrepit attic room. She is devoid of hope, and that is part of the key to this fantastic story. While toiling at the post office, Christine gets a telegraph message from her aunt in America - a woman she's never met. The wealthy aunt offers her a vacation at an expensive and elegant Alpine resort. Christine immediately runs to her mother to find out if this is real, and her mother explains that it is, and that her sister (the aunt) wanted her to go, but that she couldn't because she couldn't travel and that she should take Christine. Christine, utterly flummoxed by the thought of any change in the dull routine of her life, packs her small straw suitcase, and takes a train to meet her aunt. The description of Christine's arrival at the hotel are priceless and brilliant. Christine is overwhelmed by the beauty and by the elegance of everything, and she is like Cinderella at the ball. Her aunt (and uncle) are good to her, and dress her in beautiful clothing and have her hair cut in the latest elegant fashion, and have her face made-up. The scene reminded me of Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz movie - being primped and taken care of from every angle. Christine is so excited, and so astounded at her ability to feel anything but sadness and tedium, that she cannot sleep for the first night. She feels like her eyes have been opened to the beauty of the world, and she wants to take it all in. This is all from Part One, of this two part novel. If you want absolutely no spoilers, don't read on (and don't read the back cover of the novel) - although I recommend that you do and that it won't take away from your enjoyment of this novel. For me, knowing a little bit in advance only enhanced my reading experience. Part Two is a far different story, although it takes place immediately afterwards. Christine, like Cinderella, has been returned to the hovel, but now it all becomes unbearable because she has experienced and seen the other side. Christine befriends a man named Ferdinand, a bitter war veteran, who s

"Which way shall I fly? Infinite wrath and infinite despair?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

. . . and in the lowest deep a lower deep, Still threatening to devour me, opens wide, To which the hel l I suffer seems a heaven." John Milton, Paradise Lost There are some books that you can finish, put back down on the table and five-minutes later have it virtually erased from your consciousness. Stefan Zweig's "The Post-Office Girl" stayed with me long after I put the book down. It is a brilliantly crafted book that looks at the mind-boggling despair that can crush the soul out of just about anyone. What makes the book memorable is the fact that Zweig does not write with an overwhelming appeal to pathos. No, instead, Zweig is direct and his narrative manages to convey this sense of despair without drowning the reader in rhetorical devices aimed at soliciting sympathy for his characters. The setting is post World War I Austria in the 1920s. The Austro-Hungarian empire has been dismantled after the Treaty of Versailles and Austria, like her ally Germany, is suffering the `economic consequences of the peace'. The Post-Office Girl is Christine Hoflehner. At the war's outset, Christine and her family enjoyed a comfortable middle-class existence in Vienna. But the war and the economic suffering brought on by the hyper-inflation of the 1920s has booted Christine out of Vienna and her middle class life. She and her mother live at the poverty level in a one-room bed-sitter in a village two hours from Vienna. Christine works as a low-ranking postal official in the town's post office. As the story opens she's in her 20s and merely going through the motions. But her robot-like existence is shattered when she receives a telegram (a big event) from an aunt, her mother's sister, who left Austria before the war and married a rich American businessman. They invite Christine to spend a holiday with them in a Swiss mountain resort. Christine goes grudgingly but is astonished at the life she is exposed too. Her aunt buys her beautiful clothes, feeds her well and all of a sudden Christine is exposed to a life she never knew existed. She takes to it immediately. She relishes her new life and cherishes every minute of it. But no sooner has she found a new life than she is tossed back into the old one. Any despair Christine may have felt before her Swiss trip is now magnified by the fact that she has actually seen how different life can be. She arrives at what she thought was the lowest deep only to discover that there are depths of despair yet to go. It is at this point that she finds Ferdinand on a day trip to Vienna. For Ferdinand life has been, if anything, more unkind to him than to Christine. Their meeting and their developing relationship takes us through the second half of the book. They know they are soul mates but their existence is such that they each know that love (if you can call their fumbling attempts at personal physical and social intimacy love) is not nearly enough to be of any help to them at all. They face the questio

Capitalism with the gloves off

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

While Stefan Zweig's greatness as a writer has never diminished in Europe, he is much less known than he should be in the US. His novels as insightful, psychologically penetrating, and often charged with emotion. The characters in Zweig's fiction are often in a state of crisis: honorable people who have blundered into an impossible situation (or been thrust there by the forces of society). Zweig's ability to see deeply into the workings of the human psyche shouldn't be too surprising: he was, after all, a close personal friend of Sigmund Freud. "The Post-Office Girl" (a remarkably prosaic title for a book Zweig called "Intoxication of Transformation") is a late work, and remarkably bitter. Zweig often wrote about the impact of World War I on European culture, and in this work we get a male and female perspective on the hideous poverty that occurred in Austria after the War. Both of the main characters have been screwed by life. Christine lost her father and brother during the war, and ends up in a dead-end job, taking care of her ailing mother. She doesn't seem to realize how miserable her life is until a wealthy aunt offers her a vacation in Switzerland, and she sees what she's been missing. Returning to her drudgery, she's furious with the inequality of life, and when she meets Ferdinand, an equally angry veteran who has been struggling to get by since returning from a prison camp in Siberia, the two form an instant connection. Zweig uses Christine and especially Ferdinand to provide himself with a voice to lay bare the horrors of war, and the crushing burden that economic inequality creates. The self-absorbed, wealthy people Christine encounters on her vacation are played in high contrast to her petty bourgeois brother-in-law. It's hard to say which is more memorable: Zweig's depiction of the lavish splendor of Christine's vacation, or his gritty, realistic descriptions of the cheap cafes and flea-bag hotels where Christine and Ferdinand spend their time. What he does document brilliantly is the Austrian mindset of embitterment after World War I. After all, it was from that mindset that Adolph Hitler would rise to power, on a message of hope for working class people to again rise up out of their depths.

with the backdrop of 1930's Nazism

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

The Post-Office Girl is fastpaced and hardboiled--as if Zweig, normally the most mannerly of writers, had fortified himself with some stiff shots of Dashiell Hammett. It's the story of Christine, a nice girl from a poor provincial family who gets a taste of the good life only to have it snatched away; and of Ferdinand, an unemployed World War I veteran and ex-POW with whom she then links up. It's a story, you could say, of two essentially respectable middle-class souls who wake up to find themselves miscast as outcasts, but what it's really about, beyond economic and psychological collapse, is social death. Set during the period of devastating hyper-inflation that followed Austria's defeat in 1918, Zweig's novel depicts a country grotesquely divided between the rich and poor, so much so that it has effectively reverted to a state of nature. Christine and Ferdinand and Austria have been hollowed out (even if the country is still decked out in the pomp, circumstance, and pointless bureaucratic regulations of its bygone imperial heyday). They exist in a Hobbesian state of terminal desperation from which--the discovery arrives with mounting horror and excitement--the only hope of escape or redemption lies in violence. Zweig wrote The Post-Office Girl in the early 1930s, working on it during years that Hitler rose to power and that saw Zweig, as a Jew, forced into exile. He appears to have considered the book finished, and yet he left it untitled and made no effort to publish. Why? My own hunch is that it was just too close to the bone. Zweig was famous all over the world as a writer of fiction and non-fiction and as a public intellectual. He was, you could say, the standard bearer for a certain liberal ideal of civilization, for a way of life that is worldly, compassionate, cultivated, tolerant, sensitive, self-aware, and reflexively touched with irony; the life of, as he considered himself, a man of taste and judgment. In the face of Nazism, such an ideal may have come to seem so much wishful thinking, and certainly Zweig, in exile, found his whole reason for living undercut. This, it seems to me, is the trauma that The Post-Office Girl registers. It accounts for the raw power and relentlessness of the book, for its difference from his other work, and also, I imagine, for Zweig's uneasiness about it. He couldn't put it or the reality it describes in perspective. I don't think that it's an accident that The Post-Office Girl, though finished in the mid-30s, finds Zweig rehearsing a scenario for suicide that clearly anticipates his and his wife's deaths in Brazil in 1942. Found among Zweig's papers after his death, The Post-Office Girl did not appear in German until 1982, when it was published as Rausch der Verwandlung (a phrase taken from a crucial early episode in the novel, translatable as "the intoxication of metamorphosis"). Zweig's letters refer to his "post-office girl book," and we have chosen to follow this lead. An equally good title, als