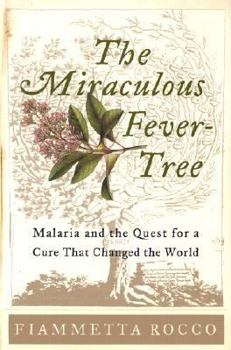

The Miraculous Fever-Tree: Malaria and the Quest for a Cure That Changed the World

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

"Cinchona revolutionized the art of medicine as profoundly as gunpowder had the art of war." -- Bernardino Ramazzini, Physician to the Duke of Modena, Opera omnia, medica, et physica, 1716 In the summer of 1623, ten cardinals and hundreds of their attendants died in Rome while electing a new pope. The Roman marsh fever that felled them was the scourge of the Mediterranean, northern Europe and even America. Malaria, now known...

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0060199512

ISBN13:9780060199517

Release Date:August 2003

Publisher:Harper

Length:348 Pages

Weight:1.55 lbs.

Dimensions:1.2" x 6.0" x 9.0"

Age Range:14 to 17 years

Grade Range:Grades 9 to 12

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Informative and Entertaining

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

I found this book to be very informative and a pleasure to read. It recounts the story of malaria and quinine in an entertaining manner. It is very antithesis of a dry science-history that imparts the necessary information but in the process bores the reader to death. The author has personal experience with malaria and weaves this into the story, giving it a more human dimension. This is not to say that the book is about her and her family, although this is discussed. The book recounts the history of malaria, its impact on history in general, the search for a cure, and how this cure was implemented. It tells how the bark of a plant located thousands of miles away from the centers of malaria contagion was found to be a cure and how this was brought to the attention of the whole world. The reader learns how Jesuits brought the bark of the miraculous fever tree to Rome, how the value of the drug produced from it was debated, denigrated and finally accepted. The book also recounts the economic aspects of the story, from the attempt to prevent trees being grown outside their natural habitat, thereby marinating a lucrative monopoly, to the planting of forests in Asia and Africa, to the development of chemically produced alternatives and their impact on these forests. The book also discuses the important military aspects of this story, from its impact on the Napoleonic Wars, the American Civil War to WWI and WWII. The complex life cycle of the malaria parasite is discussed, as is the story of how this very complex riddle was solved. This may not be the definitive book on malaria and quinine, but in my opinion the story was covered in sufficient detail for me and in a manner that I greatly appreciated. I recommend this book to those interested in the history of medicine, history in general and to all those who appreciate a well-written non-fiction book.

A well-crafted, beautifully written book

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Books about things that "change the world," are still popular and relevant to the non-fiction reader. A classic example is Fiammetta Rocco's, Quinine: Malaria and the Quest for a Cure That Changed the World (Harper Collins, 2003), a book that traces the history of quinine from its discovery in the 17th Century by Jesuit missionaries in Peru to its use by expanding European colonial powers and its role in the development of modern anti-malaria pills. The priests learned of the bark of the cinchona tree, which was used by Andean natives to cure shivering, at a time when malaria, then known as Roman ague or marsh fever, was devastating southern Europe. The Jesuits eagerly began the distribution of the curative bark, which also helped European explorers and missionaries survive the disease as they entered new territories. The interest generated by Rocco's book is due to her delving into the relationship between man and plant and that as she demonstrates so well, a plant substance can be dealt with at a personal level. She also is the great-granddaughter of Phillipe Bunau-Varilla, a soldier and engineer and at one time the Panamanian ambassador to the United States. A genius in the art of lobbyist statecraft, he has been referred to as the "Inventor of Panama," and was called one of the most extraordinary Frenchmen to ever live, and he, like his granddaughter survived malaria, so Rocco knows about malaria and quinine from street level, so to speak. She also has the advantage of being a really good writer and having travelled or lived in many interesting places. Well-crafted, beautifully written, it is book well worth the read.

Bitter pills

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Subtitles about X "that changed the world" are off-putting, because most such books are superficial or narrow-minded, or both. Not "Quinine." Although Fiammetta Rocco's approach is idiosyncratic, it is thorough. She visited many of the key places, from Peru to the Congo, and she read some of the original documents. Also, she has had malaria herself and comes from a family with an intimate association with the disease, from Panama to her childhood home in Kenya. In the hands of a less skilled writer, her discursive approach would not have worked. Here, it works charmingly. Not that the story has much charm of its own. Not only is malaria a nasty disease, the men who found the cinchona tree and guessed it would treat the fever and who fought among themselves over religion and profits often, ended up half- to fully mad. The whole thing is so improbable. Malaria existed only in the Old World, the fever-tree only in the Andes of the New World. The locals drank a powder of the very bitter bark to ease the shakes, which gave the idea to a Jesuit that it might treat the fever in Rome -- at that time, 1630, fever was thought to be a disease, not a symptom. The intellectual battles over this cure helped to dismantle the belief in Greek medicine, and, much later, the investigation of the disease's transmission also opened up an unexpected area of natural history -- human parasites mediated by insects. One word that does not appear in "Quinine" is "vaccine." Largish sums of money and very large hopes are being invested in finding a malaria vaccine. There are reasons to think this venture will never succeed. At any event, Rocco ignores this avenue to concentrate on the tried-and-true cure. She also, thankfully, says not a word about global warming and the expansion of malaria. Malaria is not a tropical disease -- a point she makes repeatedly -- and a warmer world will not extend its reach. It is a disease of poverty, and she includes a world map of malaria's empire in the 21st century that makes the point clear. Her day job is as a literary editor in London, and she includes a list of novels in which malaria features. It is this sort of personal intrusion that helps raise "Quinine" well above the usual level of techno-historical writing.

Bark, bugs and battles

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

This engaging account sketches the investigation and quest for a cure for the "mal 'aria" of Rome. "Mal 'aria" was once thought to emanate from the "bad air" of swamps and marshes. Rocco, herself a victim of this dread illness, narrates its impact from ancient times into the modern world. When the death of a pope brought 55 cardinals to Rome to replace Gregory XV, 10 of them had contracted malaria within two weeks. Those who survived returning to Sees in European nations spread further a malady already prevalent in many nations as distant as the British Isles and Scandinavia. Even as the papal successor, who was also prostrated with chills and fever, struggled to survive the infection, some of his minions were advocating a likely cure against great skepticism.Jesuit missionaries in the New World discovered Native Americans using a powdered tree bark to treat fevers and "agues". Sending the powder back to Catholic Europe introduced the first therapy for malaria, probably just as these same interlopers were infesting the Western Hemisphere with the parasite. Cinchona powder, diluted in wine to cover its bitterness, verged on the miraculous. As Rocco describes its effect, she also recounts the resistance to the "Jesuit powder" in Protestant Europe, particularly Britain. Lack of enthusiasm, plus military ineptness, led to a malarial onslaught in 1808, when an English attempt to invade Napoleon's empire ended in disaster.Empire, war and malaria remained in close company throughout the 19th Century. British incursions into west Africa were stalled by the infection. At one point the medical records indicated more cases of malaria than there were settlers - due to repeat hospital patients. Even against this severity, progress was being made. It's said "there's always one" and Rocco shows how one dedicated man made an immense difference. On a voyage up the Niger, Baikie imposed a strict daily regimen of quinine dosage. One of his crew was murdered and one drowned - but none were lost to malaria.Returning to the Western Hemisphere, Rocco describes the inept handling of fevers by the in the American Civil War. Vicksburg, she asserts, failed to be taken due to the Union's lack of quinine for its troops investing the city. Even greater disaster awaited the French in their attempt to link the Atlantic and Pacific with a Panama Canal. Instead of treating the workers, the French merely hid the casualty list and hired replacements. Even as late as World War II, battlegrounds in the Pacific highlighted the need for plentiful supplies of quinine. By that time, however, some synthetics had been developed. Malaria, however, is neither easily diagnosed nor treated. Rocco notes that there are several versions of the illness, and many varieties of cinchona. Matching them takes skill.At the end of the 19th Century, malaria had been identified as a parasite, not the effusion of swampy fumes. Rocco describes the labours of British Army doctor Ronald

The Unwon Battle of Cinchona Against Malaria

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

The most devastating disease to humans has undoubtedly been malaria. Fiammetta Rocco is qualified to write about the disease. She has had it herself, and her father had it many times. Her grandparents kept a farm in Africa, and while it can be expected that there were plenty of diseases to bother or kill, malaria was the most prevalent. The story of the battle against malaria has been told many times, but since it combines science, the conquest of nations, and religion, it will always prove inexhaustible. In _The Miraculous Fever-Tree: Malaria and the Quest for a Cure that Changed the World_ (HarperCollins), Rocco has focused on the discovery, utilization, and culture of quinine, the drug that for centuries has brought some hope against the disease. That it has had to work for centuries, of course, means that the battle is far from won.Perhaps the most malarious city in the world was Rome. It was said that the many marshes around the city provided "bad air" (how the disease gets its name), but of course they actually provided breeding grounds for the mosquitoes that spread it. When there was a convocation of cardinals, for the eventual election of Pope Urban VIII in 1623, there was a clash of politics, philosophies, and personalities, but the most worrisome aspect of the meeting was that one cardinal after another sickened and died. At just about that time cinchona bark started coming in. That it was a miracle cure is clear, and part of the wonder was that a constant scourge of Europe had a cure growing in dense forests in the mountains halfway around the world. Jesuit priests in missions in the Andes saw that natives used it to stop the shivers when exposed to dampness and cold, and when it was tried on malaria, not only did it work to ease the shivering, it took away the other symptoms of the disease. It became know as "Jesuit Powder," and Protestants protested against its use; it also seemed to contradict the humoral theory by which medicine was done at the time. Its efficacy meant that it would conquer such prejudices, but Rocco shows how in one world war after another, the medicine was not available to troops who needed it.Malaria is still a killer, one person succumbing about every fifteen seconds. The pharmaceutical industry is generally uninterested in researching and producing medicines for tropical diseases, and the artificial substitutes for quinine have resulted in resistant strains. But surprisingly, the Jesuit Powder has barely sparked any resistance, and it still works. This detailed and fascinating book ends with the optimistic outlook for the company Pharmakina, based in the Congo, which is simply growing cinchona trees, harvesting the quinine, and selling it at affordable prices. Such an operation won't do for the big drug companies, but sensible profits from a reliable product represent good business. This is a reminder that for all the colorful and dramatic history of malaria and our efforts to treat it, the