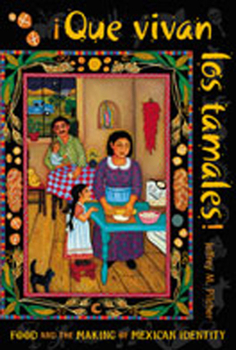

Que Vivan Los Tamales!: Food and the Making of Mexican Identity

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Connections between what people eat and who they are--between cuisine and identity--reach deep into Mexican history, beginning with pre-Columbian inhabitants offering sacrifices of human flesh to maize gods in hope of securing plentiful crops. This cultural history of food in Mexico traces the influence of gender, race, and class on food preferences from Aztec times to the present and relates cuisine to the formation of national identity. The metate...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0826318738

ISBN13:9780826318732

Release Date:April 1998

Publisher:University of New Mexico Press

Length:253 Pages

Weight:0.87 lbs.

Dimensions:0.7" x 6.1" x 9.0"

Customer Reviews

2 ratings

Que Vivan Los Tamales

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Book is a good review on the origins and development of mexican cuisine. I found it very interesting how certain foods were associated with certain classes of people in Colonial and 19th century Mexico. Reading about the mechanization of the tortilla held a strong meaning for my family, since my great grandmother was effected by it when she lived in Mexico during those times! -Danny

Excellent!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 25 years ago

(From Planeta magazine): Mexico's fiery cuisines stand in sharp contrast not only with traditional European cooking but also with each other. The regional variations and menus make Mexican cuisine one of the most sophisticated in the world. In a new book published as part of the University of New Mexico Press's Dialogos series, author Jeffrey Pilcher uses food itself to provide a unique, insider's guide to Mexican history and politics.ÁQue vivan los Tamales!: Food and the Making of Mexican Identity (ISBN 0-8263-1873-8, 234 pages, University of New Mexico Press, 1998,$16.95 or $37.50 hardback (ISBN 0-8263-1872-X) examines the evolution of mestizo recipes - the blending of Old and New World spices to make the famous turkey mole or gourmet flourishes, such as cuitlacoche rolled in crepes and covered with bechamel sauce.The author praises the creative role cookbook authors played in unifying the country's taste buds, especially in the 19th and 20th centuries when a national identify was being forged and the construction of railroads and highways lowered the costs of distribution of exotic agricultural products so that local specialties could be enjoyed throughout the country.Much of the book traces the differences and debates stirred by promoters of maize and wheat. Elites often criticized maize, and even suggested that the corn-eating population was at a serious disadvantage in terms of development. Their reasoning: the wheat-consuming Europeans were on top of the world, not the corn-eating Americans or rice-eating Asians. But such prejudices were not easily resolved. The problem was (and is) that corn simply grows better in Mexico than wheat.It's hard to understand the desire upper-class Mexicans had to break from their indigenous heritage. Throughout the colonial period, corn was under attack and likewise the construction of homes and buildings using adobe, a centuries-old technique used the world over and perfected in many of the regions in Mexico.Instead, colonial architects favored European-styled architecture, European-styled clothes and European-styled foods. Pilcher explains the logic of the time: "One did not have to be born a European, it was sufficient to act like one, dress like one, and eat like one."In reality, Pilcher says that "the tortilla discourse really served as a subterfuge to divert attention to social inequalities... Rural malnutrition resulted not from any inferiority in tortillas; instead, poverty, particularly the lack of land, made it impossible to obtain a well-balanced diet."The book is loaded with colorful tidbits, such as Christopher Columbus' description of lizard : "tastes like chicken," he said -- perhaps using this present-day cliche for the very first time.Pilcher also recounts how during the colonial period more beef was available than wheat bread. Priests were slow and often hesitant to use corn for communion wafers, though chocolate was sometimes consumed (covertly) at