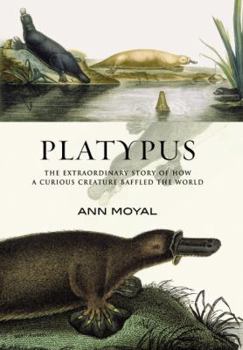

Platypus: The Extraordinary Story of How a Curious Creature Baffled the World

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

When the first platypus specimen reached England from Australia in 1799, the scientific community claimed that it was a hoax. On closer investigation, dubious European naturalists eventually declared... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:1560989777

ISBN13:9781560989776

Release Date:July 2001

Publisher:Smithsonian Books (DC)

Length:226 Pages

Weight:1.00 lbs.

Dimensions:0.9" x 5.5" x 8.1"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

A hsitory as interesting as the animal

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Ann Moyal's "Platypus" is really two stories in one. As the tital suggests one of those stories is the history of the scientific struggle to understand an animal originally thought to be a chimaera and hoax. The second story is that of the people, preconceptions, and politics surrounding the science of natural history in the decades preceding and immediately following the Darwinian revolution of scientific thought. Moyal, through the narrow lens of a platypus-centralized story tells of the struggles, missteps and transformation of western science from franco/clerical to anglo-colonial/secular domination, and finally to the global excersise it has become today. It is fascinating that many of the greatest names in 18th and 19th century science (Cuvier, Meckel, Home, Geoffrey St-Hilaire, Owen, Darwin) all studied to some degree the anatomy and biology of the platypus! The difficulties in studying the platypus are recreated in the pattern and pace of Moyal's prose. The overall progression of the book is temporal, but the chapters focus on the individuals and many of the chapters begin by backtracking in time to follow the story of another player in the story. This allows Moyal to explore each portion of the story she is telling as a series of mini-biographies, but requires diligence on the part of the reader to keep maintain an orderly timeline. What was even more suprising is the size of the book, 15 chapters covering 205 pages (in an 5 in. X 8 in. format) with glossary (incomplete, but good for non-scientists), references, and index bringing the total to 226 pages. Out of the box my first impression was that is was too short. However, by the end of the book I felt satisfied that Moyal had adequetly, though not exhaustively, recounted the history of the study of the playpus and illuminated the position of this enigmatic creature as a focal point (one of many to be sure) of contention and controversy during a crucial period in the maturation of biological science.

WOW!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

This book was an amazing story of how one small creature stumped a bunch of stuffy scientists. It really taught me about the platypus, and amused me at the same time. Kudos to the author.

Beautiful scholarly treatise.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Ann Moyal's portrait of the evolution of science with the Platypus as the centrefold was richly rewarding. The detail is a blessing as is the easy description of scientific terminology. I probably learnt as much about science as I did about the platypus. Complaints ? I don't read fiction so I love this stuff and it was too short. C'mon Ann, what's next ? *****

A Weird Animal's Role in Evolution

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

The platypus is such a quiet and secretive creature, it is hard now to comprehend that during the nineteenth century it created a firestorm of controversy, or at least as much of a firestorm as academic biology endures. The extent of the controversy, and the history of science's dealings with the strange creature, are the subjects of _Platypus: The Extraordinary Story of How a Curious Creature Baffled the World_ (Smithsonian Institution Press) by Ann Moyal. If you know little about the creature, you can learn plenty here, but more important is the story of how humans attempted to capture, understand, and classify the animal and how it came to play a role in the great debate over evolution.The platypus was such an oddity that at first no one believed it could actually exist. With an animal that was an amphibian quadruped with webbed feet, fur, and the beak of a duck, it is not surprising that some suspected a hoax. Central to classifying the platypus were the two questions concerning reproduction: did it produce live young, and did it produce milk for them? Richard Owen, the most influential naturalist before Darwin and who had an encyclopedic knowledge of anatomy of many species, was able to confirm the stories that the reclusive platypus did suckle its young, but the question of birth proved more troublesome. The obvious way to settle such a question would be to find a platypus home and see, but the retiring and removed nature of the creature prevented this for decades. Instead of suspending judgement on the question until this could be done, naturalists formed ranks on different sides, and argued over the issue in what seems now a useless and puzzling manner. Owen, originally a friend of Darwin and then a fierce opponent of evolution, tended to examine evidence to show his own view that the platypus had live birth, but it was not until 1884 that a naturalist shot a platypus which had laid an egg and had another coming down the cloaca. The long controversy was ended, and the aging Owen must have heard the news, but unfortunately his views on the discovery are unknown.Moyal's book is beautifully illustrated, with pictures of the platypus as envisioned by naturalists through the centuries. It is full of interesting facts about one of the most peculiar creatures on the Earth, one which has yielded surprising findings even after the big controversies were settled. For instance, although there is no placenta to connect the young with the mother platypus, the egg within the uterus is nourished by absorption into its shell, a process which egg-laying birds and reptiles do not share. Another surprising finding, and this only in the last couple of decades, is that the distinctive bill of the platypus (and it isn't hard like a duck's, but soft and flexible) contains a battery of electroreceptors which are so sensitive they can detect the tiny muscle discharges of the shrimp and worms on which the platypus feeds. The platypus, as revealed in this well-writ

Exhibit A for Natural Selection

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

The humble platypus, which few have seen in the wild, created more biological debate in the 19th century than any other animal. In the 20th century, observations led to startling new findings about how the platypus reflects advanced evolutionary development. When I went to Australia, the platypus was on my most-hoped-to-see list. Fortunately, there was a nice habitat in the Sydney zoo that helped me to learn more about them. The platypus uses burrows as its land home, but spends a lot of time in the water. The platypus can consume half its weight a day in live food. To locate that much food, it relies on an advanced electrolocation method involving its duck-like bill. This method is more effective than the sonar-like methods used by other animals. Well, what is a platypus? First, you notice the duck-like bill. Perhaps a bird? Second, you notice the fur. Perhaps a mammal? Third, you see the webbed feet. Back to bird? Fourth, close examination shows that the platypus has mammary glands. Mammal? Fifth, the platypus lays eggs that are like those of reptiles. Reptile? These days, the view is that the platypus is a mammal that lays eggs, along with the echidna. But both animals confounded 19th century naturalists before Darwin when Divine Creation was the dominant theory of evolution. Elaborate classification schemes had been developed that traced everything into one neat family or another. The platypus did not fit. The first specimens were sent back pickled in alcohol to England and later to France, where dissection sparked a continuing debate about whether or not the platypus had mammary glands and whether or not their young could suckle. How the young were born was a complete mystery. The mystery could have been solved much sooner, but Europeans chose to ignore what Aborigines and Australians told them about the platypus. So European naturalists came and slaughtered thousands, looking for pregnant and ovulating female platypuses. Attempts to transport platypuses live failed for a long time, as did attempts to maintain them in captivity. Eventually, observations by European naturalists established the truth. By the time that Darwin wrote The Origin of Species, the platypus had become one of his greatest examples of natural selection. The platypus had kept some reptile-like features while having evolved into a mammal. Little did he know that the bill's sensors would become the strongest evidence for his argument. The book is well illustrated with many drawings and a few photographs that provide helpful perspective on this little-known creature. Ms. Moyal does a fine job of giving us a Down Under view of all this. She combines solid science, explained simply, with a subtle wit about the false speculations and plodding methods of pompous, well-respected scientists. You will enjoy what she has to say. After you finish this fine book, I suggest that you think about where the evidence around you contradicts what you hav