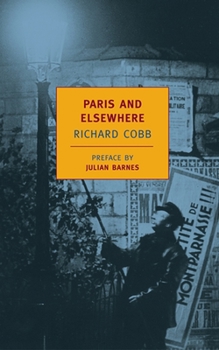

Paris and Elsewhere: Selected Writings

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Richard Cobb, the incomparable historian of the French revolution, had an affinity with France that went beyond academic interest. Living there in the years after the Second World War, he acquired, he... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:1590170822

ISBN13:9781590170823

Release Date:March 2004

Publisher:New York Review of Books

Length:334 Pages

Weight:0.86 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 5.0" x 8.0"

Customer Reviews

1 rating

Bittersweet chronicles of a now lost Paris

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

This collection of Cobb's essays is another book in the NYRB series which I did not want to finish reading. These essays are about more than Paris or Normandy or even Europe; here is a record left by an Englishman who passionately loved a place, a bi-cultural historian and writer who grew his soul between the rare archived records of France and the living streets he loved. Richard Cobb has shown me that writing a memoir of place is a sensory experience. His essays are so rich in textured intimacy that I feel "le Cobb" is living still. One can find him strolling down an avenue observing every alteration of the weather, every change in the pavement, in the passersby, their clothing and language. I imagine Cobb still sitting in his favorite haunt, the late night and early morning caf?, sipping the 4:00 a.m. calvados, or apple brandy, as he watches the barges come up the river. From his youth, to his late travels, Cobb had found that one cannot write history without knowing the living. Le Cobb called himself a "prisoner of habit" (301), and this, I believe, is the key to the depth of detail in his writing. He frequented the same places, the same towns, kept in touch with the same French and Belgian friends. But there is also something exquisitely lonely about Cobb, the solitary observer, that appeals to the wounded romantic in every traveler. I'm concerned that the general reader will not pick up this book; the density of language in Paris and Elsewhere appears to be for the intimate specialist only. But the essays are about desire for a place, about human interaction in that space, how people create each other's lives, and the anger and grief one feels when a beloved city or village is altered forever--phenomena and feelings which anyone can apply to anyplace in the world. I highly recommend this book for people involved in city planning, the New Urbanists, any reader wondering why the French no longer wear berets, or any reader looking for a context or background as to how or why the recent riots and rebellions occurred across France in the past year. Cobb loved France enough to criticize the French particularly in the decades from the Baron Haussman in the mid 19th-century to Georges Pompidou in the 1970s when so much destruction was visited upon Paris in the name of `architecture.' Cobb shows that Brussels and Paris sustained more damage after World War II than before: "The damage which has been inflicted on these two cities is not, then, the result of enemy--or Allied--action" (200). In Paris distinctive neighborhoods were destroyed by the French themselves with no concern for how people's lives were being altered or the monoculture being created. Well, Monsieur Cobb, this vandalism to intimate dwellings, social settings, tiny restaurants, private gardens, the homes and boulevards of experience, is now a global condition. Thank you so much, Professor Cobb, for such beautiful writing on such a bittersweet topic.