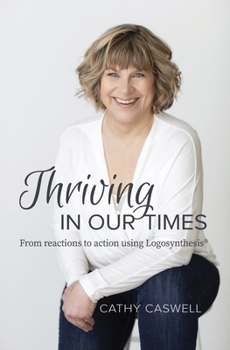

Thriving In Our Times: From Reactions to Action using Logosynthesis(R)

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

This book, Thriving In Our Times: From Reactions to Action using Logosynthesis(R), is a guide for leadership and personal development during times of change and uncertainty.

We live in a rapidly changing and uncertain world. It can be challenging to recognize how our conditioned reactions influence how we feel and how we interact with others. We have an opportunity to learn how to resolve what bothers us so that we feel better. This book shows you use Logosynthesis, developed by Dr. Willem Lammers, to provide relief from distressing thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations. In this process, you will experience a sense of calm, clarity and confidence to take meaningful action. The Healthy Living Plan, based on the principles of Logosynthesis, offers a guide to help you clear your path during these uncertain times.

This book is based on the author's personal experience using Logosynthesis in her everyday life, including times of change and uncertainty. 'As I reflect on my life choices, I can now observe that my patterns of behavior are based on my beliefs, attitudes, and experiences.These patterns have served me well. Work hard. Help others. Stick with it. Yet I can also observe where these patterns have become rigid and overused. When I experience change and uncertainty and my energy is stuck in these patterns, it can be difficult to see other ways of doing things. My automatic responses can feel intense and distressing, for myself and for those around me. Logosynthesis allows me to clear my path to move forward with greater ease and clarity.'

For leadership and personal development, this book will guide you to use Logosynthesis so that you can thrive in our times, as an individual within your family, your workplace and your community. Enjoy!

Related Subjects

Biochemistry Biological Sciences Biology & Life Sciences Chemistry Earth Sciences Evolution General & Reference History & Philosophy Humanities Inorganic Language Arts Linguistics Science Science & Math Science & Scientists Science & Technology Social Science Social Sciences Words, Language & Grammar