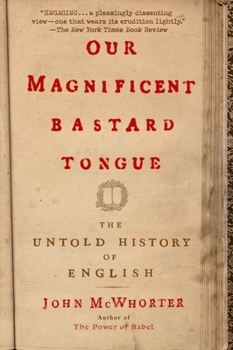

Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue: The Untold Story of English

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

A survey of the quirks and quandaries of the English language, focusing on our strange and wonderful grammar Why do we say "I am reading a catalog" instead of "I read a catalog"? Why do we say "do" at all? Is the way we speak a reflection of our cultural values? Delving into these provocative topics and more, Our Magnificent Bastard Language distills hundreds of years of fascinating lore into one lively history. Covering such turning points as the little-known Celtic and Welsh influences on English, the impact of the Viking raids and the Norman Conquest, and the Germanic invasions that started it all during the fifth century ad, John McWhorter narrates this colorful evolution with vigor. Drawing on revolutionary genetic and linguistic research as well as a cache of remarkable trivia about the origins of English words and syntax patterns, Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue ultimately demonstrates the arbitrary, maddening nature of English-- and its ironic simplicity due to its role as a streamlined lingua franca during the early formation of Britain. This is the book that language aficionados worldwide have been waiting for (and no, it's not a sin to end a sentence with a preposition).

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:1592404944

ISBN13:9781592404940

Release Date:October 2009

Publisher:Avery Publishing Group

Length:256 Pages

Weight:0.43 lbs.

Dimensions:0.7" x 5.0" x 7.2"

Age Range:18 years and up

Grade Range:Postsecondary and higher

Related Subjects

Etymology History Language Arts Social Science Social Sciences Words, Language & GrammarCustomer Reviews

5 ratings

Comprehensive lok at English

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

It is hard reading in places but a very good read for students of our language.

A nearly perfect book about a fun topic

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

I'm a language book nerd from way back, and familiar with the issues McWhorter tackles in this book - the odd usage in English of recruiting "do" as an auxiliary verb ("Do you like fish?"), and the odd present-progressive ("I am writing a review.") Nonetheless, I learned a lot new here. Both of these usages are rare around the world, very rare. McWhorter does a good job of explaining the scholarly debate, and his own view (the influence of Welsh and Cornish), but the book reads breezily and easily, for all the erudition. (In fact the only slight criticism I'd make is that it reads a bit too breezily at times, as if McWhorter is worried he's going to turn people off being too clever and too technical for too long. Not a problem.) After this main argument, the book goes on to the Viking and Norman influences on English and some other topics. If you like either language or history, it's fun. If you like both, more fun still.

Unique analysis of English development

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

This unique analysis certainly isn't included in most college courses. The author argues certain unusual features in English grammar come from Welsh. He argues they are undocumented in ancient records since no one wrote in Welsh, and the only early written English was a non-conversational, formal form. He further argues most modern English scholars don't know enough (or care enough) about Welsh to see the forest for the trees. And, he argues our lack of gender in nouns comes from broken English spoken by early Viking raiders. Very readable, but very redundant. Could have been half as long. Now to track down and read his detractors!

Celts and Vikings and Phoenicians, Oh My!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue by John McWhorter (Gotham Books) is the most entertaining book about linguistics that I've read. As a teacher and writer, I love English and its quirks, but I never could get my mind around all the charts, graphs, and jargon of formal linguistics. This book gave me a nice language fix without sounding like a calculus text. It's relevant to mention that McWhorter is black, because a racial subtext runs through this book. McWhorter's linguistic specialty is Creole languages--those lilting mash-ups created by black slaves out of native tongues and European languages. In Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue, he suggests that English is a kind of Creole, and chides "traditional" linguists for ignoring the way English was "gumbo-ed" by the Celts, Vikings, and Phoenicians. First, McWhorter attempts to show that Celts had a significant effect on Old English, evident in our unique use of the "meaningless do" (we say "Do you want to go shopping" whereas all other languages say something like "Want you to go shopping?") and progressive constructions (we say "Mary is singing" whereas all other languages say something like "Mary sings."). In another chapter, McWhorter agrees that Norse invasions of Angle-land caused many of our inflectional endings to drop off but goes further and insists that Norse influence truly battered our grammar. Finally, McWhorter goes out on an intriguing limb in proposing that Phoenician influenced Proto-Germanic (he gives as evidence striking similarities in Germanic and Semitic words). In the middle of these assaults on traditional linguistics, McWhorter pops in a rant against grammar rules, insisting that all grammar is just fashion. All of this is fascinating and persuasively argued, with loads of examples; in fact, the avalanche of examples might bury all but the most committed reader. The "racial" undercurrent is an unspoken--well, partially spoken--complaint that traditional linguists want English to have a "purer" history than it does, and that the influences McWhorter argues for are those of common people speaking English, rather than educated people writing English. Traditional linguists dismiss the possibility of Celtic or Phoenician influence, McWhorter implies, just as they refuse to accept Creole tongues as real languages. Even the "all grammar is fashion" chapter carries a whiff of the Ebonics debate. However, McWhorter's tone is always good-humored, and he writes delightfully. He makes strong cases for his theories, though I don't know enough formal linguistics to counter-argue (and McWhorter seems to be fluent in about forty different tongues!). I'm willing to agree with much of what he says, though I'm not as ready to dismantle Standard Written English as he is. If you enjoy English as a language, if you are curious about how and why we say things the way we do, if you like a good CSI story, and especially if you've wanted to know more about the history of English but were intimidated

"A Revisionist History of English"

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Linguist John McWhorter in his latest work advances a very well argued contrarian view of the development of the English language. The prevailing conventional view is that changes in English over time principally involve just the addition of new words from Latin, French, and, in the ages of exploration, words from everywhere. The conventional view rests centrally on the "hard evidence" reflected in surviving writings. Very adroitly, McWhorter reminds us that in early societies the written language was scribal and thus no necessary reflection of what the bulk of the non-literate population actually spoke. Nonetheless, the conventional view at its narrowest takes what merely survives in writing as a picture of the whole, imagining in doing so that it is being scientific and avoiding "airy assumptions." History, however, McWhorter reminds us, invariably involves much that is lost, requiring as well a reconstruction of events based on high levels of probability. McWhorter rests his contrarian case on such arguments as he deals with other surviving bits of circumstantial evidence. His chief argument is that the history of English may best be understood as a consequence of the mixing of languages, not merely the addition of new words from foreign sources or the consequence of changes that "just happened." He seeks to explain the principal changes, not merely and dully to document them. Starting with the invasion of the British Isles by Angles, Saxons, and Jutes after the Roman departure, McWhorter disputes the notion that these invaders completed a successful Holocaust on the native Celtic peoples. He contends that two of the oddest features in English, separating it not only from other Germanic tongues but from all the other world's languages as well are the meaningless "Do" in such questions as "Do you do the dishes?" and in negatives, "No I don't do them," and the use of the present progressive, "I am doing the dishes," where other languages normally use just the present form, "I do the dishes." McWhorter's reminder is that these oddities were found in the neighboring tongues of Welsh and Cornish, and nowhere else. Occam's razor points to the conclusion that these Celtic tongues added certain features to Old English grammar, features which only become apparent in documents once English writing years later comes closer to actual English speaking. While the Celts added such features to old English, the later Viking invaders, learning English as a Second Language, stripped it of many of its "hard" to master Germanic attributes. Thus, Old English had many of its endings shaved off, and it stands alone among European languages as free of gendered nouns. McWhorter also presents a compelling critique of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis that a specific language's grammatical structure determines the thought patterns of its speakers. His convincing rebuttal is that homo sapiens in essential respects are alike the world over, and that their needs and interests i