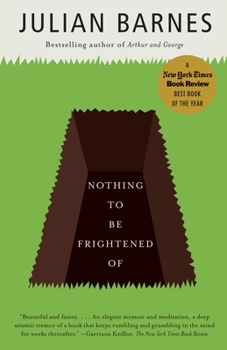

Nothing to Be Frightened Of: Nothing to Be Frightened Of: A Memoir

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

NATIONAL BESTSELLER - From the bestselling, Booker Prize-winning author of Sense of an Ending, "an elegant memoir and meditation" (The New York Times Book Review) that grapples with the most natural thing in the world: the fear of death.

A memoir on mortality as only Julian Barnes can write it, one that touches on faith and science and family as well as a rich array of exemplary figures who over the centuries have confronted...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0307389987

ISBN13:9780307389985

Release Date:October 2009

Publisher:Knopf Publishing Group

Length:256 Pages

Weight:0.62 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 4.9" x 8.2"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

A free man thinks of nothing more than Death

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Julian Barnes is a bit old - fashioned. He has written a book about the fear of dying without considering the possibility 'Death' too is just another contingency which technological human beings will be able to invent themselves out of. In short in this work the work of people like Aubrey de Grey who believe life will one day be extended indefinitely, or Ray Kurzweil who believes the intelligences which will replace us will not be organic passers from the world. Instead Barnes takes what is given all the evidence we have a not unreasonable position , that each and every human being dies. This is the 'nothing' to be frightened of, the nothing of our not being. Barnes tells us that since childhood not a day has passed without his thinking about his own mortality. And now that he has hit sixty there is no diminishing of his concern about the subject. But the book does not focus exclusively on his attitude towards death. In fact what is extremely interesting is what he tells us about others attitude Death, both those of his own family and those writers like Montaigne, Philip Larkin, Jules Renaud, Goethe. Barnes writes beautifully and surveys brilliantly the opinions of a wide variety of writers and thinkers on the subject of Death. As one who does not believe in God but 'misses Him' the paradoxical quality of much of this thought is apparent. I found the most interesting parts of the book to be his considerations of the attitudes of famous others to Death. Thus he notes for instance Goethe's seeming disdain for Death as he struggled to pursue his own independent way of life. Barnes considers the work of Dr. Sherwin Nuland whose pioneering research told a general audience just how horrible Death often is. All in all this is a very fine book although it does not my mind explore religious 'answers' to Death in a sufficient way. Nor does it consider fully enough the way for many belief in God is the only final meaningful answer to Death. For the religious believer there is a kind of defiance, "Death where is thy sting? Death where is thy victory?' which I suppose those who believe only in our complete disappearance with Death cannot have.

memoir on mortality

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Novelist Julian Barnes (b. 1946) was never baptized and has never attended a church service in his life, and so he's never had any faith to lose. He came by this unbelief honestly; his father was an agnostic and his mother said that she didn't want "any of that [religious] mumbo jumbo." But the certainty of total extinction, both personal and cosmic, and the terror which absolute annihilation provokes in him, causes Barnes to admit in the first sentence of his book that while he doesn't believe in God, he misses Him. The title for his disquisition on death comes from one of his journal entries over twenty years ago: "People say of death, 'There's nothing to be frightened of.' They say it quickly, casually. Now let's say it again, slowly, with re-emphasis. 'There's NOTHING to be frightened of.' Jules Renard: 'The word that is most true, most exact, most filled with meaning, is nothing.'" Exactly where the emphasis on nothingness rightly falls is what occupies Barnes' considerable talents. The result is a book characterized by deeply personal candor and broad-ranging critical inquiry that encompasses art, music, philosophy, science, literature, and family memories. The Christian story claims that Jesus "conquered death and brought life and immortality to light through the Gospel" (2 Timothy 2:10). This story succeeded, says Barnes, not because people were gullible, because it was violently imposed by throne and altar, because it was a means of social control, or because there were no other alternatives. No, the Christian story succeeded because it was a "beautiful lie" (53) or "supreme fiction" (58). It's the stuff of a great novel, "a tragedy with a happy ending." And good novelists, says Barnes, tell the truth with lies and tell lies with the truth. There's always a "haunting hypothetical" for Barnes: what if this Grand Story is true? The strictly secular-materialist option is simple enough. When your heart and brain cease to function, your self ceases to exist. But in this view the "self" is nothing more than random neural events. There's no ghost in the machine to begin with, so in fact there's no "self" that ceases to exist. In post-modern parlance, personal identity is a social construction. But Barnes has nagging suspicions about this neat and clean scientific scenario. Even if they are hard to define or describe, a common sense outlook, endorsed by the vast majority of humanity that has ever lived, is that intelligence, aesthetic imagination, our moral impulse, consciousness, love, gratitude, guilt, regret, and the longing for immortality -- all of these seem to point beyond themselves. They have the ring of truth that makes them hard to define by mere biology. And so Barnes wonders, given his genuine lack of religious faiith, is it proper to seek and to assign any meaning to his personal story? Does his life enjoy a genuine narrative? Or is it only a random sequence of events that ends with

Julian Barnes Confronts Mortality with Savoir Faire.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

"For me, death is the one appalling fact which defines life; unless you are constantly aware of it, you cannot begin to understand what life is about; unless you know and feel that the days of wine and roses are limited, that the wine will madeirize and the roses turn brown in their stinking water before all are thrown out for ever -- including the jug -- there is no context to such pleasures and interests as come your way on the road to the grave. But then I would say that, wouldn't I?"--Julian Barnes English novelist, Julian Barnes, is best known for his second novel Flaubert's Parrot (1984) and his more recent novel based on the life of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Arthur & George (2005). In his superb new memoir, Nothing to Be Frightened Of, Barnes confronts the subject of human mortality. Now at age 62, death is something he not only thinks about every day, it sometimes that sometimes roars him awake at night, the effect of which has given Barnes a bittersweet appreciation of life, or as Somerset Maugham might call it, a "humorous resignation" toward life. Prompted by the wake-up call to the reality of his own certain death ("le réveil mortel"), Barne's memoir is not so much a personal history of his life, as an "amateur" (as he calls it) philosophical meditation on his own inner world in the final act of his life. While there are frequent references to Barnes' friendships (or "memories of friendships") and family (who "are likely to reclaim you in death") along the way, Barnes' memoir is populated to large extent by the French writers and philosphers who have given his life meaning: Jules Renard, Flaubert, Montaigne, Stendhal, Flaubert, Zola. For Barnes, religious faith is not an option. The athiest turned agnostic admits he is envious of those with religious faith. "I don't believe in God," he writes, "but I miss Him." More specifically, he misses "the God that inspired Italian painting and French stained glass, German music and English chapter houses, and those tumbledown heaps of stone on Celtic headlands which were once symbolic beacons in the darkness and the storm," because he considers Christianity a "beautiful lie . . . a tragedy with a happy ending." Science provides Barnes with little solace either, for "there is no separation between 'us' and the universe," he writes. Scientists have discovered no evidence of individual "self." Barnes insightfully examines the state of modern existence filled with daily reminders (bumper stickers and fridge magnets) reminding us that Life Is Not a Rehearsal; "our chosen myth" that our relationships, jobs, material possessions, property, foreign holidays, savings, sexual exploits, exercise, and consumption of culture equate to happiness; and America's ability to reconcile religion with "frenetic materialism." He reveals his admiration for those who simply remain true to themselves as they approach their inevitable ends, finding sublime pleasure in the world, even as they are leaving it,

On Death and Dying

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Julian Barnes in NOTHING TO BE FRIGHTENED OF has written a thoughtful, sometimes humorous treatise on death that begins with the lines: "I don't believe in God, but I miss him." He contrasts his views-- an atheist at twenty but now an agnostic at sixty-two-- with those of his philosopher brother, who remains an atheist. His story meanders-- or in his words it "lollops"-- in the way we expect from a novelist; and I am sure it is far more interesting, at least for me, than a more logical one that his professor brother would have written. Mr. Barnes attempts to be brutally honest about both himself and his family although he is quick to admit the unreliability of memory and quotes many events from his family's past where he and his only brother have totally different recollections about the same event. His parents, at least as he remembers them, are an interesting pair. "I'm sure my father feared death, and fairly certain my mother didn't: she feared incapacity and dependence more." Barnes regrets that he father never told him he loved him although he is pretty certain that he did. He reserves his harshest criticism, however, for his mother. She would prefer deafness to blindness, were she given a choice, because she wanted to be able to do her nails. After the death of his father, Barnes, though attentive to his mother, would never spend the night with her. "I couldn't face the physical manifestations of boredom, the sense of my vital spirits being drained away by her relentless solipsism, and the feeling that time was being sucked from my life, time that I would never get back, before or after death." Barnes, rather than quoting the clergy and medical community, for the most part quotes from many of his favorite writers and other artists on death: Shostakovich, Ravel, Zola, Flaubert, Somerset Maugham, Jules Renard, even William Faulkner who said that a writer's obituary should simply read "He wrote books, then he died." Some of Mr. Barnes' observations and conclusions: We escape our parents only to become them. Religion makes people behave no better or worse. He fears both death and what it takes to get there, the loss of memory ("memory is identity") and the loss of bodily functions. He is fairly certain that he will die in hospital and alone. The fear of death, at least for Barnes, doesn't "drop off" after the age of sixty as one friend of his believes. Finally he concludes that as a youth he was sure that art survived the temporal. He now reminds us that "Even the greatest art's triumph over death is risibly temporary. A novelist might hope for another generation of readers--two or three if lucky-- which may feel like a scorning of death, but it's really just scratching on the wall of the condemned cell. We do it to say: I was here too." When Barnes asks a Catholic friend of his with whom he has lunch on his [Barnes'] sixtieth birthday why he is a believer he responds he wants to believe. I was reminded of Reynolds Price's many books on r

Lively Thoughts on Death

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Novelist Julian Barnes thinks a lot about death. And he doesn't like it; he describes himself as "one who wouldn't mind dying as long as I didn't end up dead afterwards." Naturally death has been part of some of his books, but in _Nothing to Be Frightened Of_ (Knopf), death takes center stage in what is a memoir and an essay on a popular subject. Everybody thinks about dying, but Barnes has used his thoughts to power a book that is funny (look at the two meanings in that title), sad, informative, and earnest. Barnes quotes many stars from history about the big subject, like Freud, who said that it was impossible for any of us to imagine our own deaths. Barnes strongly disagrees. He is 62, and does not give any intimation of ill-health, but since adolescence he has been thinking about his own death, and those of others. He isn't morbid. "I am certainly melancholic myself," he writes, "and sometimes find life an overrated way of passing the time; but have never wanted not to be myself anymore, never desired oblivion." The inevitable end is coming, however, so Barnes seems to be saying let's look at it seriously, and learn and laugh, and keep it in mind to season the days of our lives. Just remember, as he says, "that the death rate for the human race is not a jot lower than one hundred per cent." Barnes's family had a family Bible, but it was someone else's family's, bought at auction, "... and was never opened except when Dad jovially consulted it for a crossword clue." His father was a "death-fearing agnostic", his mother a "fearless atheist", and much of his book has to do with how the two of them interacted, and then, well, died. The other family member frequently consulted in these pages is Barnes's older brother, an analytic philosopher and expert on ancient Greek, who lives in France, teaches, and keeps llamas. The brother has come very close to death, and even breathed out what it seemed were going to be his last words: "Make sure that Ben gets my copy of Bekker's Aristotle." Barnes remarks that the wife of the philosopher found this "insufficiently affectionate." For an unbeliever, Barnes finds God all over the place. Barnes reflects that the important divide may not be between believer or nonbeliever, but between those who fear death and those who don't. He tells us how he conquered his fear of flying; perhaps he will conquer his fear of death, but he admits that even writing about it, which other people would think an exercise "to get it out of your system", does not work. It doesn't matter. Barnes has a terrific subject, and if he doesn't have firm answers, he has great questions which any reader will enjoy thinking about. After all, as he quotes Montaigne, "The end of our course is death. It is the objective necessarily within our sights. If death frightens us how can we go one step forward without anguish?" Barnes himself wonders at the beginning, "How is it best to write about illness, and dying, and death?" A