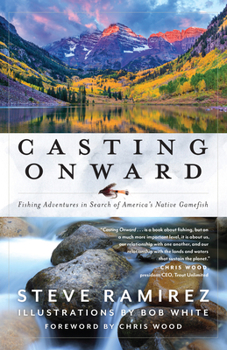

Casting Onward: Fishing Adventures in Search of America's Native Gamefish

In writing Casting Onward, author Steve Ramirez traveled thousands of miles by plane, motor vehicle, boat, and foot. The focus is the author's extension of Casting Forward by fishing for native fish within their original habitats, and telling the story in part through the eyes of the people who have lived alongside, and come to love, these waters and fish. It is a story of fishing and friendship - a story of humanity's impact on nature, and nature's impact on humanity.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:1493062298

ISBN13:9781493062294

Release Date:May 2022

Publisher:Lyons Press

Length:280 Pages

Weight:1.10 lbs.

Dimensions:1.3" x 6.3" x 9.0"

More by Maxine Evans

Customer Reviews

1 customer rating | 1 review

There are currently no reviews. Be the first to review this work.