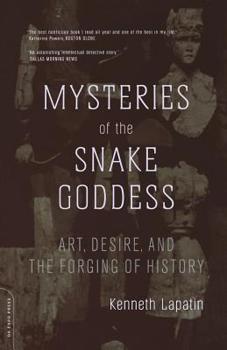

Mysteries of the Snake Goddess: Art, Desire, and the Forging of History

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Not only is one of the most famous pieces of ancient Greek art-the celebrated gold and ivory statuette of the Snake Goddess-almost certainly modern, but Minoan civilization as it has been popularly imagined is largely an invention of the early twentieth century. This is Kenneth Lapatin's startling conclusion in Mysteries of the Snake Goddess-a brilliant investigation into the true origins of the celebrated Bronze Age artifact, and into the fascinating...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0306813289

ISBN13:9780306813283

Release Date:December 2003

Publisher:Da Capo

Length:288 Pages

Weight:0.84 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 5.5" x 8.2"

Customer Reviews

4 ratings

Sorry, there is no evidence of matriarchy on Crete.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

This is a fascinating, if disillusioning, detective story. But it confirms what I have long uneasily suspected when I lectured my students about Minoan art -- that many, indeed MOST of my assumptions rested on modern recreations of that art, rather than the hard evidence of the original objects. Lapatin convincingly demonstrates here what I suspected but didn't want to believe about the exquisite Boston ivory. More important, however, he helped me understand what I can trust and what I can't about the heavily restored sculpture and painting from Knossos. Of course we all tend to interpret history in light of our own experiences; that's a fact of life. However, some historians and archaeologists go farther overboard than necessary. Evans, to give him the great credit he deserves, had a wonderful and empathetic imagination, and his discovery of an ancient civilization was an extraordinary achievement. But even in his own time, his determination to make such extensive restorations to the art and architecture was controversial. One more observation: the less we know about an ancient civilization, the easier it is for us to idealize it. Even as recently as the 1960's, Crete was usually described as a peaceable kingdom, despite the rather suspicious fact that its royal symbol was the battle axe. As for matriarchy, I hate to disappoint a previous reviewer, but the evidence for matriarchy in ancient Crete consists of two statuettes that come from secure archaeological proveniences, and a great many forgeries. The fact that the people of ancient Crete worshiped goddesses doesn't make them unusual; so did the citizens of classical Athens, whose city housed one of the most magnificent images of that goddess ever created. But their women had about the same legal rights as their goats. Final note: Read this and then read Arthur Phillips's entertainingly black-comic novel "The Egyptologist," for a take on the same phenomenon that Lapatin describes here.

Snake Goddess, Fake Goddess?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

Readable, concise, and absorbing account of the way archaeological interpretation and the manufacture of forgeries is influenced by current trends and fashions. Sheds light on the extent to which Minoan discoveries were 'tailored' to fit their discoverers' expectations. Very important reading for anyone who is interested in 'interpreting' the art and artifacts of Knossos and Minoan culture. Otherwise, one would never know that many of the now-accepted images of Minoan culture were highly 'edited' and even created by Arthur Evans and his employees at Knossos. If anything the book is too concise and focused on the Snake Goddess. I'd like to have seen a bit more on Evans' background and life. I'd stop short of calling it an 'expose',' but it certainly shows how archaeologists -- especially the gentleman adventurers of the nineteenth and early twentieth century -- were able to play fast and loose with the 'facts' to their own advantage. In fairness to Evans, he comes off as a well-meaning, if egotistical type more guilty of self deception than guile. But his complicity in the illicit trade in relics is documented.

The Importance of a Forgery

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

For over eighty years, within the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, pride of place has been given to the Snake Goddess, a statue that is sixteen centimeters tall. She is a spectacular sculpture, long regarded as the pinnacle of Minoan art from the sixteenth century BCE. She is of delicately carved ivory decorated with gold, a sensuous figure in a wide skirt of multiple tiers, a narrow, belt-encircled waist, and a bodice cut so low that her ample breasts are visible. She holds snakes in her outstretched arms. She pouts. She is one of the most famous pieces of ancient art in the world, a superb example of Cretan Bronze Age sculpture.Except she isn't. Kenneth Lapatin, President of the Boston Society of the Archeological Institute of America, has been studying her for a decade, and casting doubts on her authenticity. Now he has published a book-length explanation, _Mysteries of the Snake Goddess: Art, Desire, and the Forging of History_ (Houghton Mifflin Company) of how the experts of art and archeology have been fooled, and with the book's exhaustive notes and appendices, this account is devastating. It also tells plenty about how archeology is done, what sort of characters do it, how we view the ancient past, and how wishful thinking, perhaps even more than greed, has perpetrated the forgery. The details of the origin of the statue are still unclear, and probably always will be. But Lapatin has dug into as much as can be known of its shadowy past, and has provided an expert's details. He can write, for instance, "Eyes with drilled pupils _and_ canthi have no parallel in Aegean sculpture and do not appear in ancient statuary before the second century A.D." He gives an excellent section on why science can provide only limited evidence in this case (although none of it points to the statue's authenticity). Lapatin does more than just debunk, for in his fascinating and original book, he shows how the Goddess is still important. She isn't the find Sir John Evans, the excavator of Knossos, and others thought she was. However, "She has provided a canvas on which archeologists and curators, looters and smugglers, dealers and forgers, art patrons and museum-goers, feminists and spiritualists, have painted their preconceptions, desires, and preoccupations for an idealized past." We may have to admit we know less about Minoan culture, but we can always learn more about human nature.

Good on the details. Sketchy for the bigger picture.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

Lapatin does a good job in sleuthing through the surviving letters and other documentary evidence. He reaches the conclusion, mirrored by the lab report contained in an appendix to the book, that the "Boston Snake Goddess" is almost certainly a twentieth century forgery. He reveals that it is impossible to carbon-date the ivory of the figurine itself, because of the techniques used to restore it. Ivory fragments associated with the find but not used in the reconstruction date back about four hundred years. The chemical composition of the gold in the find does not match ancient gold. The facial expression is unlike genuine examples of Minoan art, lacking either the archaic smile or the manga-style eyes of genuine artifacts. His verdict is stated with caution, but the evidence seems to weigh against the authenticity of the Goddess. He also catalogues a number of similar statues, some of which are definite forgeries, and others have similarly dubious histories. These images nevertheless reappear over and over again, not only in historical, but also in popular literature. They were adopted into popular culture, in fantasy novels, and as feminist symbols. They even became the keystone of enthusiasts' attempts to revive the worship of this apparently invented deity. Where his argument breaks down is when he attempts to present the broader context. He asserts that Evans, the chief excavator at Knossos, was influenced by prevailing intellectual trends in positing ancient Crete as an idyllic society practicing a goddess-worshipping earth religion. In fact, though, he presents very little of Evans's own conclusions in making this argument. Where his theory comes from, and why it was wrong, is treated much less thoroughly in this slim book. Influential successors obviously influenced by Evans's theories, like Robert Graves, are not discussed at all. For a readable summation of the influence of Frazer's -Golden Bough-, and the other literary sources of the sort of beliefs that apparently influenced Evans, Ronald Hutton's -The Triumph of the Moon- does a much better job.