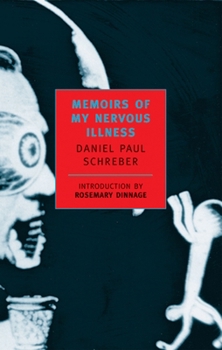

Memoirs of My Nervous Illness (Psychiatric Monograph)

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Daniel Paul Schreber: Denkw rdigkeiten eines Nervenkranken Der Jurist Daniel Paul Schreber wird 1893 zum Senatspr sidenten am Oberlandesgericht Dresden ernannt als ihn - zum zweiten Mal in seinem... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:094032220X

ISBN13:9780940322202

Release Date:January 2000

Publisher:New York Review of Books

Length:488 Pages

Weight:1.12 lbs.

Dimensions:1.3" x 5.2" x 7.9"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Soul murder and a Miracled Up World

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

An extraordinary account by Daniel Paul Schreber of his breakdown, his "hallucinations", his journey. A classic book in psychiatry. It is thrilling. So many of the terms he uses vibrate with us today: soul murder, nerve rays, his connection with God which involves both control and surrender, the way his hallucinations enabled him to act out being a woman in sexual intercourse (something he thought about just before he went mad). Freud spoke of hallucinations as restoring lost objects. Schreber spoke of a blackout in which the world (and self) were destroyed, then "miracled up" (his term) again in a new key. Freud's writings on Schreber (based on Schreber's memoir) are a must too. The two together make one of the most thrillng trips through a mad dimension that is relevant for every human being. I write of both Schreber and Freud from a contemporary viewpoint in my chapter on Schreber in The Psychotic Core. Right now I happen to be thinking of Phillip K Dick - the words that most appear in a word count of his writings were psychosis and schizophrenia. I don't know if he read Schreber or Freud's account of Schreber - but he would have loved them. Michael Eigen Author, Flames from the Unconscious

The Metaphysics of Mental Illness

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

One of my most cherished books in my library. This book is easy to misunderstand, in its intent and its revelation. I cannot even claim any authoritative knowledge, so this is only an interpretation. I think that the history of horrible and sadistic abuse at the hands of his father and the fact that his elder brother became mentally ill as well and then committed suicided only overshadows the importance of Schreber's experience and message. Knowing his history allows the reader to be dismissive about the authenticity of his experience. And that is exactly what one should not do. What should strike the reader is how "sane" Schreber comes across as with the rational, almost objective and detached, and lucid way he writes about his illness and experience in the book. He is most definitely in control of his cognitive functions and he proves this to be the case by being freed from institutionalization and returning to the bench. That said, he is still utterly convinced of the truth of his experience, and while able to function quite normally, he refuses to see his experience as delusional, that is, he still believes in the authenticity of his experience and his religious and metaphysical claims. It was this point that intrigued me the most. Now, if you were to be institutionalized for paranoid delusions, you would not be released if you maintained that your delusions were real and not delusions (at least, the doctors would not recommend you leaving even if you checked in voluntarily). How is the reader to take the paradox that Schreber presents: is he truly mentally fit by the end of the book or is he still ill due to his insistence upon the reality of his delusions? It is this problem that should make the reader begin to take Schreber more seriously and allow them to analyze the philosophy in his experience instead of glossing over it as sick fantasy. Or should we take Schreber seriously? In analyzing the world view in his memoirs I would say we should give him a charitable reading. Because of my conviction, I think of this book as more of a work of philosophy, specifically metaphysics, than the writings of a madman. While this memoir is an insightful look into the mental constructs of a paranoid schizophrenic it holds much more in its pages that needs to be accounted for. It is well known that schizophrenics have a tendency towards entertaining, as well as acting upon, strange religious constructs of their own mind (modulo the question why, that is for the psychotherapist to answer) but a treatment of Schreber's highly developed and thorough system would not be a waste of time and should be taken up. Here are some particulars that come to mind: his incorporation of a misunderstood zoroastrianism, his developed cosmology/cosmogony that includes a concern of extraterrestrial states of the universe, his preoccupation with evil and redemption, concern over the state of affairs of reality versus his own, an insistence on his own existential import i

What else you should know:

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Others who have posted reviews of this book are certainly correct in their assessment -- it's engaging, harrowing, enlightening, etc. HOWEVER, nobody has addressed the actual CAUSE of Schreber's insanity which, of course, is key to the reading of his memoir. The patient in most cases, and certainly in this case, is unable to tell us matter-of-factly what is troubling him. Instead, he tells us of his dreams or his imaginings, or his horrible delusions. It is then the psychiatrist who untangles the web. I can't recommend highly enough, as a companion to Schreber's memoir, the book "Soul Murder: Persecution in the Family," written by the psychiatrist Morton Schatzman. The book is now out of print, but can still be found used. Instead of describing the book,I'll quote from the jacket flap: "Daniel Paul Schreber (1842-1911), an eminent German judge, went mad at the age of 42, recovered, and eight and a half years later, went mad again. It is uncertain if he was ever fully sane, in the ordinary social sense, again. His father, Daniel Gottlieb Moritz Schreber (1808-1861), who supervised his son's upbringing, was a leading German physician and pedagogue, whose studies and writings on child rearing techniques strongly influenced his practices during his life and long after his death. The father thought his age to be morally "soft" and "decayed" owing mainly to laxity in educating and disciplining children at home and school. He proposed to "battle" the "weakness" of his era with an elaborate system aimed at making children obedient and subject to adults. He expected that following his precepts would lead to a better society and "race." The father applied these same basic principals in raising his own children, including Daniel Paul and another son, Daniel Gustav, the elder, who also went mad and committed suicide in his thirties. Psychiatrists consider the case of the former, Daniel Paul, as the classic model of paranoia and schizophrenia, but even Freud and Bleuler (in their analyses of the son's illness) failed to link the strange experiences of Daniel Paul, for which he was thought mad, to his father's totalitarian child-rearing practices. In "Soul Murder," Morton Schatzman does just that -- connects the father's methods with the elements of the son's experience, and vice versa. This is done through a detailed analysis and comparison of Daniel Paul's "Memoirs of My Nervous Illness," a diary written during his second, long confinement, with his father's published and widely read writings on child rearing. The result is a startling and profoundly disturbing study of the nature and origin of mental illness -- a book that calls into question the value of classical models for defining mental illness and suggests the directions that the search for new models might take. As such, the author's findings touch on many domains: education, psychiatry, religion, sociology, politics -- the micro-politics of child-rearing and family life and their relation t

The Poetry of Madness

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

Shortly after the death of Daniel Paul Schreber, Sigmund Freud used his (Schreber's) memoirs as the basis for a fantasy of his own. Everyday readers are lucky that Schreber wrote down so much of what he saw, heard and felt during his many years in German mental asylums, for his own observations are far more artistic and harrowing than anything Freud ever wrote.In this book, Schreber takes us into his world--the world of the genuine schizophrenic. He writes of the "little men" who come to invade his body and of the stars from which they came.That these "little men" choose to invade Schreber's body in more ways than one only makes his story all the more harrowing. At night, he tells us, they would drip down onto his head by the thousands, although he warned them against approaching him.Schreber's story is not the only thing that is disquieting about this book. His style of writing is, too. It is made up of the ravings of a madman, yet it contains a fluidity and lucidity that rival that of any "logical" person. It only takes a few pages before we become enmeshed in the strange smells, tastes, insights and visions he describes so vividly.Much of this book is hallucinatory; for example, Schreber writes of how the sun follows him as he moves around the room, depending on the direction of his movements. And, although we know the sun was not following Schreber, his explanation makes sense, in an eerie sort of way.What Schreber has really done is to capture the sheer poetry of insanity and madness in such a way that we, as his readers, feel ourselves being swept along with him into his world of fantasy. It is a world without anchors, a world where the human soul is simply left to drift and survive as best it can. Eventually, one begins to wonder if madness is contagious. Perhaps it is. The son of physician, Moritz Schreber, Schreber came from a family of "madmen," to a greater or lesser degree.Memoirs of My Nervous Illness has definitely made Schreber one of the most well-known and quoted patients in the history of psychiatry...and with good reason. He had a mind that never let him live in peace and he chronicles its intensity perfectly. He also describes the fascinating point and counterpoint of his "inner dialogues," an internal voice that chattered constantly, forcing Schreber to construct elaborate schemes to either explain it or escape it. He tries suicide and when that fails, he attempts to turn himself into a diaphanous, floating woman.Although no one is sure what madness really is, it is clear that for Schreber it was something he described as "compulsive thinking." This poor man's control center had simply lost control. The final vision we have of Schreber in this book is harrowing in its intensity and in its angst. Pacing, with the very sun paling before his gaze, this brilliant madman walked up and down his cell, talking to anyone who would listen.This is a harrowing, but fascinating book and is definitely not for the faint of

A very strange, but profound work

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

To begin with, the reader should be forewarned that what the author suffers from is not the idiomatic English "nervous illness," or mild neurosis, but a fundamentally different way of seeing the world, stated best by the author at the beginning of Chapter 5:"Apart from normal human language there is also a kind of nerve language of which, as a rule, the healthy human being is not aware." The book's profundity and the author's depth of insight are such that, after reading a few pages of the first chapter, one is reminded of nothing so much as Proust's Remembrance of Things Past: "Souls' greatest happiness lies in continual reveling in pleasure combined with recollections of their human past."....But, after this, the book becomes as disturbing as Proust is essentially soothing. For the author feels himself utterly isolated from other men, not even deigning to recognize them as men at all but as "fleeting-improvised-men" which "creates a feeling in me at times as if I were moving among walking corpses." (Ch. 15) What I found so disturbing about the elaboration of the author's viewpoint and recounting of his tribulations in the asylum is that there is something in his viewpoint that rings essentially true: We do not and can not know even those closest to us on the deep spiritual or "nerve language" level the author exists on in perpetuum. It is this essential truth combined with the author's matter-of-fact, almost cheery, tone that made reading this work such a strange experience for me. For English readers, such characters do exist in fiction (Poe's Usher kept occuring to me, and Mary Shelley's Frankenstein), but the tone of such psychically unstable characters and what we would call their nervous disposition are consonant with a mind gone awry and thus not to be taken so seriously. Of Schreber, just the opposite impresses itself upon the reader. It is this dissonance between tone and subject matter that render the book strange. For the view it expresses is essentially a dark one. If one reads closely, a terribly dark one. The only thing comparable to it is the worldview of the Gnostics: That this world is essentially some sort of mistake, and that there may be no way to "fix" it, as it were. The main reason to read the book, to my mind, is that it is a well-written,non-fiction account of a unique state of being (although readers might want to check out Proust as well as The Gnostic Religion by Hans Jonas for similarities.) But, caveat lector, the book is not for the faint of heart. It may keep you up many a night. It did me!