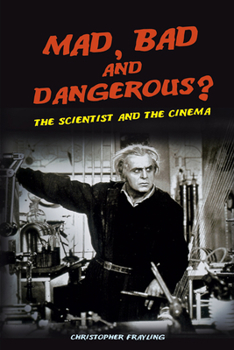

Mad, Bad and Dangerous?: The Scientist and the Cinema

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

From Victor Frankenstein to Dr. Moreau to Doc Brown in Back to the Future , the scientist has been a puzzling, fascinating, and threatening presence in popular culture. From films we have learned that... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:1861892853

ISBN13:9781861892850

Release Date:September 2006

Publisher:Reaktion Books

Length:239 Pages

Weight:0.60 lbs.

Dimensions:0.7" x 6.3" x 9.2"

Customer Reviews

2 ratings

How the Movies Made Our Image of the Scientist

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

In this book, Mad, Bad and Dangerous? The Scientist and the Cinema, Mr. Frayling has put together a fascinating study of how public perceptions of the scientist have been molded by movies. As a long time physics and math teachers well as a movie-lover, I am familiar with much of the background material he goes through. Still, I was impressed by the wide scope of Mr. Frayling's work and the well-drawn conclusions he makes. One of the techniques I sometimes use in my classroom is to have students identify math and science mistakes in the movies. This book opens with a classic--the Scarecrow's recitation of "the Pythagorean Theorem" in The Wizard of Oz. But this book really isn't concerned with such obvious mistakes. It is much more powerful is piecing together how mistakes and simplifications have led to a shorthand stereotype of the scientist we see in the movies: lab coat, glasses, disheveled hair, etc. This scientist may be the classic "mad" scientist, the distant pronouncer of hard to understand ideas, the nerd, as so on. And yet, this shorthand, often necessary for the success of a film, has become how people often actually view scientists. After briefly looking back to the classics of stage and fiction that will heavily influence the earliest silent films (Faustus, Frankenstein, etc.), Frayling digs deep into one of the most influential characterizations of a scientist on film: Rotwang in Metropolis. Half alchemist, half scientist, Rotwang is the prototype of the impossible to understand, yet powerful man who made decisions that impact all those around him. This characterization and the graphic style of Metropolis had a huge impact on the movies that followed up to the present day (see Flash Gordon to Dr. Strangelove). If you've never seen the movie Metropolis, watch it (it is excellent) and then go to chapter 3 of this book. It will open your eyes. Starting in the 1930's, there is a split. The "mad" scientist movie, which have their first peak in Frankenstein countered by the more "true" science movies like Things to Come. Both styles are still with us, though the first probably peaked with the sci-fi/horror films of the 60's while the second (a harder sell) probably peaked with the bio pics of the 40's (Madame Curie, Louis Pasteur, etc.). Frayling shows how these movie styles impacted each other and influenced our view of the scientist, particularly in the aftermath of WWII, with the arrival of the boffin movies in England and the Nazi rocket scientists in the U.S. All of which influences we still see today, as Frayling reminds us, in movies like A Beautiful Mind, Contact, The Relic, etc. There is a ton of information and analysis in the pages of this book. Insight into a number of movies as well as, more importantly, insight into our understanding of the scientist. Anyone interested in either would be foolish to pass up this book.

"You're Fu Manchu, aren't you?" "My friends call me DOCTOR."

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Mad, Bad and Dangerous: The Scientist and the Cinema is about scientists in the movies, but not just about MAD scientists in the movies. Christopher Fraying covers not only fictional new Prometheuses like Dr. Frankenstein and Andre Delambre (the scientist whose malfunctioning teleportation device turned him into The Fly), but "real" scientists like Madame Curie and Louis Pasteur. Somewhere on the seesaw between "mad" movie scientists and "good" movie scientists are what you might call the "political" movie scientists - - sometimes they're evil, sometimes they're good. (A lot depends on which side of the year 1945 it is, and whether the scientists work for the Soviets or the US.) In any event, whether they're mad, good, or political, it's important to remember these are movie scientists, and even their so-called true life stories are full of half-truths at best. They have what Frayling (referring to The Story of Louis Pasteur) calls "surface realism with a formulaic plot about the triumph of common sense." It shouldn't be surprising that a lot of twentieth-century scientists whose work intersected with the political realm were German. Frayling's chapter about the "biography" of Wernher von Braun, I Aim at the Stars, is one of the best parts of the book. (A British review of the movie biography starring Curt Jurgens was titled "I Aim at the Stars - - But Sometimes I Hit London." Even by 1960, when the movie came out, Londoners hadn't completely forgotten the V-2 rockets.) World War II affected actors and filmmakers in a similar way to the way it did scientists. In a parallel to von Braun, who first built rockets for the Nazis and then for the Americans, Jurgens himself as an actor had different identities depending on whether he was working in European or American productions. In European movies he often spoke German and was credited as Curd. In American war movies like The Longest Day, where he played "honorable" German officers, he could speak English and was known as Curt. (Jurgens wasn't a Nazi. My only point here is that European, especially German-speaking, actors - - for instance Maximilian Schell, who played the defense attorney in Stanley Kramer's Judgment at Nuremberg - - had to speak English and "act" a kind of foreigner that American movie audiences would recognize.) Later movies continued the fiction that once Hitler committed suicide the morality of German military scientists changed. In The Right Stuff one of President Lyndon Johnson's advisors says, "Our Germans are better than their Germans." But a director as perceptive (and cynical) as Alfred Hitchcock was unable to let his audience off the hook. He knew the lie he had to perpetuate in order to update a thriller like Notorious to the Cold War. (The "lie" being that there is much difference between the two sides.) So Hitchcock rubbed the audience's nose in it. In Torn Curtain the scene everyone remembers is Paul Newman as a handsome young (of course) American scientist