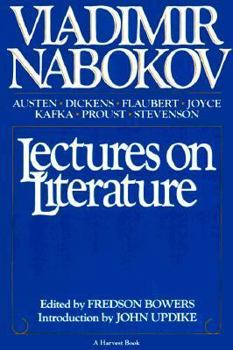

Lectures on Literature

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

The acclaimed author of Lolita offers unique insight into works by James Joyce, Franz Kafka, Jane Austen, and others--with an introduction by John Updike.In the 1940s, when Vladimir Nabokov first... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0156495899

ISBN13:9780156495899

Release Date:February 1982

Publisher:Mariner Books

Length:416 Pages

Weight:0.96 lbs.

Dimensions:1.1" x 5.3" x 8.0"

Customer Reviews

4 ratings

not just another "great writer"

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Nabokov's ideas about literature will strike many readers as strange--his near obsession with seemingly trivial points of set description, his lack of interest in Great Ideas or in "character" in the sense of a window into human nature. Such readers would likely describe Nabokov's opinions (and his own artistic creations)as "disembodied," "narrow," "cold," "sanitary." These readers would be making a crucial error, selling both a brilliant artist and themselves short. Narrative art generally operates as follows: an author presupposes the human world as a place driven by desire, a place defined by the striving for those things (white whale, justice for a father's fratricidal demise, "God") as grant freedom from pain and perhaps even transcendent joy. Drama unfolds as chracters fight over these things, great moral questions get asked (what are one's obligations to others as we strive, Does God care about us and our plans) and we feel kindred ecstacy and despair as characters near their objects or falter. To most, this is literature-- a chronicle of movement up and down a scale of nearness or distance from some highly charged, desired object. Indeed, to most, this is "reality," consciousness itself. Nabokov has a very different idea. What Nabokov understands, what is central to his conception of literature (and of consciousness), is that those objects accepted by other writers as objectively powerful things capable (however complex their identities might otherwise be) of bestowing or denying happiness, have that power only because an indvidual consciousness gives it to them. While Humbert Humbert adores Lolita, homosexual chess partner Gaston Godin is so absolutely immune to her charms that he never even realizes she's one person (he "sees" multiple Humbert "daughters"). Charlotte adores dreadful Humbert because, contrary to what we know him to be, a gallant, handsome continental is the image she makes of him. In such a world, Nabokov's world, tragedy, the final, fatal estrangement from some ultimately longed-for object, has no place: What's a fall from grace when grace was never more than a dream of the mind? Suffice it to say, the "normal" critical values of literature become equally pointless. What DOES matter in this transmorgified world is style and structure, the artistry (the Samsa house, the layer cake in Madame Bovary) with which dreamy things, in art as well as in life, are woven. What seems shallow about Nabokov, is in fact far "deeper" and subtle than anything found in such alledgely "great souled" writers as Dostoevsky, Faulkner, Thomas Mann, etc. In fact, it's no exaggeration to say that Nabokov's art begins at a point higher than than where these writers' art, at its highest, finishes.

A master's class on the art of reading

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Nabokov is a native of world literature. So it is no surprise that as he is taking the reader on a guided tour of his land, his strong literary opinions easily navigate centuries and continents of literary landscape. However, being an emotional as well as scholarly narrator, Nabokov naturally gravitates to his favorite corners of the world. He is a guide giving a tour of his native city and adding more intimate detail and color when talking about the streets where he grew up. Russian literature must occupy a very special place in his heart, since it permeated his Russian childhood, his longing for which he so beautifully described in "Speak, Memory". In "Lectures on Russian Literature", Nabokov is noticeably closer to the Russian writers than he is to the European writers in his previous volume, "Lectures on Literature" (itself very enjoyable). His spectrum of vision is wider, embracing multiple works of a writer and his personal qualities. The resulting picture is richer, the contrasts of the temperaments and styles make the writers stand out: Chekhov's altruism and Turgenev's vanity, Gogol's impressionist colors and Gorky's clichés, Dostoevsky's cold reason overwhelming his art and Tolstoy's "mighty" art "transcending the sermon", the believable and coherent worlds of Chekhov or Tolstoy and Dostoevsky's internally contradicting world or Gorky's "schematic characters and the mechanical structure of the story"... Here Nabokov continues his thought that a writer is mostly a creative artist, rather than a historian or philosopher. This is how he summarized Gogol's desperate attempts to collect facts for the second part of "Dead Souls": "[Gogol] was in the worst plight that a writer can be in: he had lost the gift of imagining facts and believed that facts may exist by themselves" (Gogol was asking his friends to supply him with descriptions of life around them which he could use in his art). Contrast with it Nabokov's admiration of Chekhov's writing for being so true to life. Chekhov invented his characters, but did it so well that they naturally created a coherent world. Nabokov always put imagination and style at the top of the writer's arsenal, and much above any "reality" (which he always mentioned in quotation marks). Nabokov clearly prefers characters to reveal themselves rather than be explained by the author: for example, where Chekhov let his characters act (not surprisingly, Chekhov was a great playwright), Turgenev tended to over-explain. In "Fathers and Sons", he uses epilogue to describe what happened next in the story. In the scene where Bazarov's father embraces his wife "harder than ever", Turgenev feels the need to explain that this happened because "she had consoled him in his grief". For the same reason Dostoevsky, whose characters Nabokov sees as "mainly ideas in the likeness of people", was not one of his favorite authors. Primacy of idea over form and style was anathema to Nabokov. Both Turgenev and Dostoevsky were too visib

The Mother Lode - Don't Miss It!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Imagine you attend Cornell, you smart devil you. You wander into the Lit class and a hawk-browed very serious tall man with glinting eyes leans out at you over the faded wooden podium. Behind him on the blackboard are a maze of drawings, dates, crisscrossing lines and circles. You look again at your syllabus - Russian Literature in translation. The black bell above the door rings, the tired muted clatter of a halting iron clanger. A rustle of books, restless students, and dead air from the closed winter storm windows rises up for just a second, then, hovering in the room shrinks to silence. The teacher begins, "Tolstoy is the greatest Russian writer of prose fiction. Leaving aside his percursors Pushkin and Lermentov, we might list the greatest artists in Russian prose thus: first, Tolstoy; second, Gogol; third, Checkov; fourth, Turgenev. This is rather like grading student's papers and no doubt Dostoevski and Saltykov are waiting at the door of my office to discuss their low marks." So begin the lectures on Anna Karenina. By the time Nabokov is done you will know more than you thought possible about the novel. You'll be comfortably familiar with the inside of an 1872 Russian railroad passenger car traveling as the night express between Moscow and St. Peterburg. To help you picture it, Nabokov draws a highly detailed sketch, with the position of each occupant, doors, windows, stove; even the direction of travel is rememebered. Wonderful as all this is, for sheer incandescent brilliance, no essay on any work in Russian Literature by any critic comes close to Nabokov's examination of Gogol's Dead Souls. Unlike Nabokov's own listing of Russian prose masters, he also comes in second as well as first, with the fulsomely captivating essay on Anna Karenina. The others offer a cross between a kaleidoscope's rendering of the fantasy behind the dummy facades with the exactitude born out of years of scientific reading. Nabokov's particular and unique genius treats us with a plethora of acute and uncanny observations, viewpoints derived from the closest possible scrutiny of the works. No book compares in this field - a marvel!

Time Travel: You Become His Student

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

I would like to thank reviewer Bruce Kendall for pointing out this book to me. This is a great book. By the way, I have one reservation about this book: it has seven chapters, one on each of seven novels, and do not read a chapter on one of the seven novel until you have read the novel. He gives lots of details and it will ruin your reading experience. Just read one novel at a time and then read Nakobov's lecture notes on that particular novel. The only exception might be "Ulysses" where most readers need help and often use a reading guide. He gives a very detailed analysis of the plot and characters for all seven works, and for one book - "The Metamorphosis" - the comments are almost as long as the 55 page story. It would be quite an experience if one could sit in on the classes of say Saul Bellow in Chicago in the 1930s and 40s when he taught literature. He recommended Flaubert, Dostoevsky, Lawrence, Joyce, and Dreiser, among others. Anyway, this is the next best thing. It is the course notes with an introduction by John Updike on the course taught by Nabokov at Cornell around 1950 or so. He was born in Russia but learned English and French at an early age. His father was murdered in Russia, and was carrying a copy of Madame Bovary at the time of his death. He went to university in England but then lived in Germany for 15 years, and then came to the Boston area where he taught at Wellesley College as just an Assistant Prof. teaching Russian 201, a survey of Russian literature. He worked simultaneously at Harvard for about 10 years, but not in literature. He then got a position as Associate Prof. of Slavic Literature at Cornell. Nabokov's main love was literature, but since he was not in the English Department, he could not teach American literature, so he gave courses on European literature. This book outlines course material prepared by Nabokov for courses 311-312, Masters of European fiction. If you read this book, it is similar to taking his course. His approach is to examine a small number of books and look at each great detail. There is lots of analysis plus some sample exam questions at the back of the book. His seven books are: Jane Austen - Mansfield Park Charles Dickens - Bleak House Gustave Flaubert - Madame Bovary Robert Louis Stevenson - Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde Marcel Proust - The Walk by Swann's Place Franz Kafka - The Metamorphosis James Joyce - Ulysses This is an excellent lecture series prepared by Nabokov with his handwritten notes and sketches. There is a note from him that he had more fun looking at the literature than the students. He was working on Lolita as he taught, and actually threw out the manuscript. His wife convinced him to continue and publish, and he was able to retire with the income from that book.