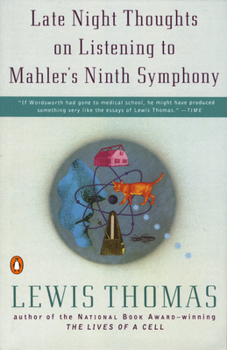

Late Night Thoughts on Listening to Mahler's Ninth Symphony

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

This magnificent collection of essays by scientist and National Book Award-winning writer Lewis Thomas remains startlingly relevant for today's world. Luminous, witty, and provocative, the essays address such topics as "The Attic of the Brain," "Falsity and Failure," "Altruism," and the effects the federal government's virtual abandonment of support for basic scientific research will have on medicine and science. Profoundly and powerfully, Thomas questions the folly of nuclear weaponry, showing that the brainpower and money spent on this endeavor are needed much more urgently for the basic science we have abandoned--and that even medicine's most advanced procedures would be useless or insufficient in the face of the smallest nuclear detonation. And in the title essay, he addresses himself with terrifying poignancy to the question of what it is like to be young in the nuclear age. "If Wordsworth had gone to medical school, he might have produced something very like the essays of Lewis Thomas."-- TIME "No one better exemplifies what modern medicine can be than Lewis Thomas."-- The New York Times Book Review

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0140243283

ISBN13:9780140243284

Release Date:May 1995

Publisher:Penguin Publishing Group

Length:176 Pages

Weight:0.35 lbs.

Dimensions:0.5" x 5.0" x 7.8"

Age Range:18 years and up

Grade Range:Postsecondary and higher

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Provocative Essays and Social Comment on Science and Humanities

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

The twenty-four, short essays in Late Night Thoughts On Listening to Mahler's Ninth Symphony remain surprisingly fresh and fascinating today. While many focus on new discoveries in biology, medicine, and physics, Lewis Thomas also offers a sobering look at the dark side of modern technology. The title essay (the last one in this collection) is particularly haunting. I almost set this book aside after reading The Unforgettable Fire, the first essay in this collection. Thomas Lewis had awakened in me uncomfortable memories of a distant past. Among my first lessons in kindergarten was to move quickly to the basement when the alarms rang, to crouch down, and to cover my neck with my hands. Along with many others of my generation, I came to accept that nuclear war was virtually inevitable. Lewis Thomas balances the more serious essays with others characterized by enthusiasm, wonder and excitement for the world about us. His observations are often surprising, and nearly always provocative. Admittedly, a few essays are becoming dated, but this collection is still quite interesting. A few examples include: The Lie Detector: our physiological response to telling a lie - even when we do it for protection or personal advantage - is sufficiently stressful to be detectable, suggesting that there is at least some physiological compulsion for humans to be honest. On Speaking of Speaking: Children not only learn languages much more readily than adults, but they seem also to play a key role in shaping and restructuring language, especially in a mixed language setting. Perhaps that period called childhood is ultimately the source of the thousands of languages and dialects that characterize human societies. On Smell: The short-lived olfactory receptor cells are themselves proper brain cells although not residing in the brain. The storage of olfactory memories remains a mystery. On the Need for Asylums: A society can be judged by how it treats its most disadvantaged, its least beloved, its mad. We must be judged a poor lot for closing institutions and turning mentally ill inmates onto the streets. The Problem of Dementia: Lewis asks not only for more funding, but for a qualitatively different approach, one that funds long term studies, freeing researchers from the need to continuously publish results. Trained at Princeton University and Harvard Medical School, Lewis Thomas held positions at the University of Minnesota Medical School, New York University-Bellevue Medical Center, and Yale University Medical School. Subsequently, he became president of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. He began publishing essays in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1971; nearly all of the essays in this collection were originally published in Discover Magazine.

What a pleasure

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

It is simply a great pleasure to read the essays of Lewis Thomas. His intelligence, his balance, his sense of wonder, his great knowledge his humility and sense of human values , his masterly and often poetic writing ability make each of the essays an adventure of discovery and delight. In the opening essay he considers the horrifying consequences of nuclear war, and argues urgently that Mankind must cease being its own worse enemy, and threatening itself in a way no natural phenomenom could. In many of the other essays he argues for the centrality of the human, and the terrestial. In surveying the cosmos he wonders at the remarkable beauty and singularity, the intricate complexity of the Earth. He writes about the sense of smell, and wonders how it is we do not have the power to reimagine what we smell the way we can reimagine and recreate what we see and hear.He returns in his essays 'Things Unflattened by Science to the subject of his first and perhaps most well- known work 'The Living Cell'. Here is a description of the evolution of the cell, a description which provides a sample of his own exceptionally clear and vivid style. "The oxygen in today's atmosphere is almost entirely the result of phosynthetic living, which had its start with the appearance of blue- green algae among the micro-organisms. It was very likely that this first step -or evolutionary jump- that led to the subsequent differntiation into eukaryotic , nucleated cell, and there is almost no doubt that these new cells were pieced together by the symbiotic joining up of prokaryote. The chloroplasts in today's green plants, which capitalize on the sun's energy to produce the oxygen in our atmosphere, arethe lineal descendants of ancient blue- green algae. The mitochondria in all our cells, which utilize the oxygen for securing energyfrom plant food, are the progeny of ancient oxidative bacteria. Collectively, we are still, in a fundamental sense, a tissue of microbial organisms living off the sun, decorated and ornamented these days by the elaborate architectural structures that the molecules have constructed for their living quarters, including seagrass, foxes and of course ourselves. '

This book will make you think.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

This is one of the most thought-provoking and eloquent books about science that I have ever read. Thomas has produced 24 essays defining what it means to be human. Through his fascination with the world, he raises a multitude of questions and points out existing uncertainties. He makes it strikingly clear that the human race has a really long way to go in order to solve the puzzles of this world. He demands solutions and answers; is there some genetic reason for the rituals that occur in nature, such as insects laying their eggs on the branches of specific trees, and then pruning these branches, thus extending the life of the trees and keeping the symbiosis in this world going from generation to generation? What is the explanation for the behavior of bees? How do you explain experiments done on people where, under hypnosis, they are told that their hands are being scalded with an iron, but in fact it is a wooden pencil, and in a short time their whole hand is red and marked? From cells to music, Thomas captures the soul of the reader and opens the door to reality with his thoughts on nature and human consciousness. This book will make you think, and the questions will linger in your mind.

The poet laureate and patron saint of sane science.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

As a one-time practicing physicist (now just an "arm-chair physicist") and lifetime music lover, I have found this beautifully-written little book irresistible over the 17 years it has been in my library. In 1983, when the original hardcover edition came out, this book was given to me as a gift by someone knowing my musical tastes, figuring that it would be the perfect gift. It turned out to be, but for reasons that are largely non-musical. As an arm-chair scientist, I've read and enjoyed more than a few popularizations by well-known scientists over the years. These include Richard Feynman with his wry humor in virtually everything he wrote (I number myself among those physicists who "cut their eye teeth" on the Feynman Lectures in Physics), Stephen Hawking, Brian Greene, Carl Sagan, and even Brian Swimme. (The Swimme of "A Walk Through Time" goes down easily, and covers much of the same ground that Thomas does, but in a quite different way; the Swimme of "The Universe is a Green Dragon" is a much harder sell for me due to its hard-pressed attempt to oversimplify.) But for sheer elegance and poetry and breadth of scope, and for essays that provoke thought on the part of the reader, none can hold a candle to Thomas. Everyone who reads this little masterpiece will have his or her favorites. Here are a few of mine: In "Things Unflattened by Science" (an essay on unaddressed and/or incomplete challenges that future scientists might well undertake), a paragraph on how biologists might endeavor to better understand what music is, and how it affects the human condition, starting with a rather small-scale assignment to explain the effect of Bach's "The Art of Fugue" on the human mind. In "Altruism" (an essay on the symbiotic interrelationships among species), how it is that such a condition actually exists, and a challenge to future scientists to better understand how our own species might become more altruistic (and adult) than it presently is. In "The Attic of the Brain" (a cautionary essay on the risks of psychiatry, most importantly psychoanalysis, in terms of performing "total brain dumps"), the need for all of us to carry around a little clutter in our lives, as insurance against the chance that we might inadvertently lose our ability to retrieve something truly important. In the title (and final) essay, another cautionary tale, this time on thermonuclear weaponry, the most lucid description I've ever read regarding the true meaning of this music as envisioned by Gustav Mahler. In a few brief but sublime paragraphs, Thomas has captured the essence of this remarkable opus in a way that no musician (and that includes such Mahlerites as Bernstein, Karajan, Klemperer, Rattle and Walter) ever had. Until very recently, that is, with the release a few months back of a staggering performance by Benjamin Zander, conductng the Philharmonia Orchestra. But that is another topic, and another review. In the seventeen

Cogent, thought-provoking and brilliant

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 25 years ago

Rarely has an author captured both the folly and innate genuis of the human species so perfectly as has Lewis Thomas in this beautifully written book. Highly recommended.