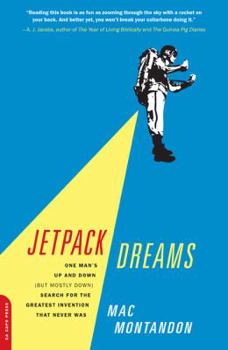

Jetpack Dreams: One Man's Up and Down (But Mostly Down) Search for the Greatest Invention That Never Was

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Jetpack Dreams chronicles the colorful pop history and science of that most amazing and mysterious of machines: the jetpack. Fueled by a fascination and lifelong obsession with the power of flight, journalist Mac Montandon goes on a vastly entertaining search of the elusive invention. He examines the jetpack's inspiration from the first shoulder-mounted wings to Bill Suitor's 1984 Olympic flight, even uncovering a gruesome jetpack-related murder in...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0306818345

ISBN13:9780306818349

Release Date:December 2009

Publisher:Da Capo Press

Length:261 Pages

Weight:0.85 lbs.

Dimensions:1.0" x 5.7" x 8.7"

Customer Reviews

4 ratings

Why I like Jetpack Dreams

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

By Galen, age 8. I liked the book because I want a Jetpack and the book was very, very funny. I liked it because it was the biggest book I have ever read. It makes me want to fly.

Envisioning the Future--When Can I Fly to Work?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

What assumptions have we made about the future? It is a good question, and one that will be answered differently by each person, but there seems to be a similarity to those assumptions when talking to American males born in the 1950s and 1960s. I am one of them, and we all seem to want to be able to vacation on the Moon and fly to work. For a lot of us, that flying to work would be on a personal jetpack that would free us from the doldrums of terrestrial life. "Where's my jetpack?" seems to be the rallying cry of these individuals, and author Mac Montandon tries to answer it in this enjoyable tour of the inventors trying to make the dream a reality. Of course, Montandon relates the history of the jetpack; how brilliant engineers at Bell Aerospace led by Wendell Moore in the 1950s came up the concept and made it work, but only for about 30 second before it ran out of fuel. The jetpack, initially thought to be a boon to American G.I.s crossing rivers and the like and therefore receiving Defense Department funding, never proved out and eventually became a stunt valued for all manner of entertainment events. It found its way into Hollywood in such films as James Bond's "Thunderball," the television series "Lost in Space," and by Boba Fett in the original "Star Wars" trilogy. It was also viewed by millions worldwide at the dramatic opening of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. While abandoned as an official project by the military, or anyone else such as NASA, the jetpack lives on in the dreams of hundreds of garage inventors who seek to build their own versions. It is those inventors that Montandon seeks out, literally worldwide, to ascertain the status of "Jetpack Dreams." The answer is that the dream is still a dream, although advocates believe success is attainable with enough investment of time, money, and brainpower. Others are not so sure, commenting that it would require repealing some of the laws of physics to create the necessary lift from such as small energy source. Montandon is an advocate himself and closes the book with a hopeful riff on how some great breakthrough might make the jetpack more than just a dream (or a short term stunt) enabling all of us to change the trajectory of the future. Don't hold your breath, but "Jetpack Dreams" represents an interesting exercise in technological exuberance. It is something we all engage in to some degree. Virtually everyone Montandon interviewed, whether an advocate or not, responded that having a jetpack would be "pretty cool." I agree. I want one as well.

A genre without a name

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

To my ear, it sounds better in French: Un genre sans nom. This may be because I have read too much literary theory. The French are big on the play of thought - le jeu de la pensée - and if it is anything, this book is full of playful thought. The book tells the story of a young man, Maccabee Montandon, who leaves his charming wife and two winsome daughters, in quest of a treasure never dug up, a prophecy never fulfilled. "Where's my (and our) damn jetpack?" he wonders. So off he goes, hoping to find a working jetpack (he does) and fly it (no luck). If this not-too-precious quasi-précis seems to have mythological overtones, well, it does. Almost anyone can point to a few mythic quest heroes - Ulysses, Batman, Leopold Bloom, Barack Obama and my personal favorite, Don Quixote. The modern age of un genre sans nom can also be referred to as "the age of colonated sub-titles." When did that conceit arise? Sometime after Mark Twain, since there is no colon in Life on the Mississippi, itself seminal in the invention of un genre sans nom. Check some contemporary examples - Positively Fifth Street: Murderers, Cheetahs, and Binion's World Series of Poker; Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values; Rebuilding the Indian: A Memoir. Luca Seriani calls this usage the "syntactical-descriptive": the colon stands as sentinel between the fanciful and the mundane. So, what is it that un genre sans nom has that others haven't got? It's got a guy (so far, most of the writers have been guys) who is looking for something. It's not a hobby kind of thing, but neither is it a Nijinskian burning madness. The guy expects to come back to the wife and kids, a little singed, maybe, but not as a box of ashes. The object of his quest has a degree of strangeness, it is quixotic. But the strangeness itself cannot be too strange. For Montandon, his quest took him out of Brooklyn, certainly, but not beyond the pale. What these guys are after is what anyone might go in search of, given the right motivation, the right wife, and/or the right literary agent. It's got the facticity of its object, as history, and the agenbite of inwit of the teller of the tale, the personal narrative. It's like a long letter home from camp. Most of all it is ex post facto, a comic ending to a tragic tease, the Quest for everyman. They charm us in another way, as well, these lovely amateurs. They enfold us in their wiles not by telling us their adventure, but by writing it. Not even Bill Suitor, the original and archetypal rocket-belteer joins so fully in Montandon's endeavor as one who has read his book. Having reassured us by giving us the book, they now inoculate us against mediocrity by making us members of their cult. The book, not the deed, is the essence of what they return us to. I think that Odysseus, having dealt with those other kind of suitors, would have enjoyed this well written book.

Pursuing the Dream

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Previous centuries didn't have science fiction as we have had science fiction. We have had descriptions and depictions of the future, from _Metropolis_ to _Flash Gordon_ to _2001_; none of the predictions comes close to what the future actually brought. No one fifty years ago could have expected the scientific and electronic marvels we have now at our fingertips. We have zipped into the future, and it is really quite wonderful, except for one very basic deficiency: "Where's my jetpack?" That's the question that is asked over and over (sometimes with a bit of profanity inserted) by freelance writer Mac Montandon in _Jetpack Dreams: One Man's Up and Down (But Mostly Down) Search for the Greatest Invention That Never Was_ (Da Capo Press). Montandon isn't the only one asking. When Bill Gates was a guest on _The Daily Show_, Jon Stewart did an abrupt change of subject and asked, "When are we going to get jetpacks?" (Gates's answer: "We're not working on that one.") Montandon came of age in the _Star Wars_ era, and "thus was very certain that by no later than the year 2000 we would most definitely be living _in the future_." The future included commuting by jetpack rather than Kias. What happened? What happened is that imagination betrayed us. Montandon gives one example after another of jetpacks in comics or movies, but points out that the power of each has to do with a fantasy people have had for as long as they have had imaginations: wouldn't it be wonderful if we could fly? A guy with a jetpack is far closer to the fantasy ideal of flight than anyone enclosed within a plane. We got serious about jetpacks in the fifties, when Tom Moore, one of Dr. Wernher Von Braun's circle of engineers and a Buck Rogers fan, got a grant of $25,000 from the Army for this innovative way of moving soldiers. When other engineers got a jetpack that could produce liftoff, test pilots strapped it on, and by the early sixties, reliable, stable flight was being achieved, lasting all of 21 seconds. One of the pilots was Bill Suitor, who became the world's best jetpack pilot. He said flying the gadget was like "standing on a beach ball bobbing in the middle of a swimming pool," but he mastered the art of flying it. It was Suitor who stood in for Sean Connery when James Bond jetpacked in _Thunderball_. He flew it for the opening of the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. And this is just about as far as practical jetpacking has come, a show that gets everyone's attention at openings of malls or state fairs - for 21 seconds. It is a toy, not a tool. That does not make any difference to the countless tinkerers who are trying to make their jetpack dreams into reality. Montandon has a fine time traveling to see these guys all over the globe, and his rollicking prose makes a reader glad to be with him. He was hoping to don a jetpack himself and try it out; he never got closer than that first step. It's the sort of expectation and disappointment that echoes t