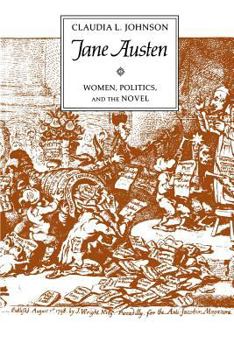

Jane Austen: Women, Politics, and the Novel

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

"The best (and the best written) book about Austen that has appeared in the last three decades."--Nina Auerbach, Journal of English and Germanic Philology "By looking at the ways in which Austen domesticates the gothic in Northanger Abbey, examines the conventions of male inheritance and its negative impact on attempts to define the family as a site of care and generosity in Sense and Sensibility, makes claims for the desirability...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0226401391

ISBN13:9780226401393

Release Date:June 1990

Publisher:University of Chicago Press

Length:212 Pages

Weight:0.69 lbs.

Dimensions:0.5" x 6.0" x 9.0"

Customer Reviews

4 ratings

Jane in her time and in ours..

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Ms. Johnson's scholarly book, which examines how Jane Austen was and is received as a woman writer, is a very thoughtful and lively one. I enjoyed it very much, and expect that it will influence future re-readings of all Miss Austen's work, especially "Mansfield Park." I will not be looking at Sir Thomas in at all the same way when I next encounter him. (I had already experienced grave doubts about Edward...) If you want a thought-provoking (though on occasion overly combative) experience of modern criticism of the Austen canon, this book will suit you very well.

Very Serious Critical Work Expands on Ms Austen's Artistry

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Here is a book chock-a-block with the intellectual universe of Jane Austen's time, a world shocked by dire French political experiments and radical thought. The major English writers and thinkers of Jane's own day, ideas 'in the air', as well as settled philosophy, come together in this densely argued study casting Jane as far more the serious artist and political thinker than her more popularized current role: the alter-ego of a Laura Ashley-costumed Elizabeth Bennett, simultaneously Cinderella and Harlequin Romance beauty, flitting hither and thither as she scribes the petty doings of village society like some chronicling cheeky gadfly, a teasing overseeing Queen of the May. As such, Ms Johnson's work helps us regain a truer sense for the genius of this most remarkable woman and artist. Johnson's book is not an easy read; it does not attempt to 'explain' themes and characters so much as reveal how extremely subtle and charged with the potential for a second look Austen's writing can be. This study repays re-reading: its density is marked by a historically and politically informed revisiting of each of Austen's major works, within an enlightening and reinforcing close reading of not only the texts, but the texts as they existed in Austen's own day and age. Each chapter sets off a sharp and trenchantly political Austen: not a general view, and one gainsaying her current air-brushed image - see the beauteous Ms Hathaway -traduced by contemporary commerce. Johnson gives us an Austen as supreme intellect, working through complex plot gradations and extraordinarily finely shaded characterizations with the dedication and deliberation of a Flaubert. More and more it appears that Austen's true heir, the author who most fully enshrined the lessons of her provocative, highly enriched langauge, was neither her devoted admirer Sir Walter Scott, nor 19th century England's greatest novelist, Charles Dickens, but the much less popular, more rarefied Henry James. Each chapter of "Jane Austen, Women, Politics, and the Novel" discusses and sets off Austen as a self-demanding writer of inner ambitions: Johnson shows Jane Austen an artist struggling with complex issues and achieving a range in her expression clearly far beyond the grasp of her contemporaries. Johnson's study helps us see Ms Austen as something a great deal larger and more magnificent in thought and art than we'd here-to-fore imagined. To give but a single instance from what seems an ever-bifurcating example; in the fine chapter on "Sense and Sensibility" the double stories of the two Elizas are revealed by Professor Johnson as bright intense flocculus previously obscured by the overall glare of plot; far-reaching motifs powerfully integrating both plot and character: "The most striking thing about the tales of the two Elizas is their insistent redunancy. One Eliza would have sufficed as far as the immediate narrative purpose...to discredit Willoughby...but the presence of two unfortunate he

A very interesting book

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

I generally avoid literary criticism, preferring to enhance my understanding of an author through history and biography, but I recently picked up three books on Jane Austen that have made me rethink my position. This is a very readable look at Jane Austen as a female author during a time when the proper behavior of woman was a hotly debated issue. In this volume, Johnson considers the literary context in which Austen was writing, and then relates each of her novels to it. This book was nicely complemented by Margaret Kirkham's Jane Austen, Feminism and Fiction, which I read about the same time. The latter approaches the period from a slightly more historical, rather than literary perspective. The two are not repetitive, but rather mutually enriching. Johnson struck me as a little more politically doctrinaire, which is a minus for me, but a plus for some. A second book that may be of interest is Alison G. Sulloway's Jane Austen and the Province of Womanhood. Sulloway is discussing the same general topic, but she chiefly focuses on writings about proper female conduct, rather than literature. I suppose that we chose our own Jane Austen, and I prefer the clear-eyed social critics whose lack of delusions have frightened some of her readers. This being the case, I particularly enjoyed Johnson's reading of Sense and Sensibility. Many critics, such as Claire Tomalin (Jane Austen: A Life), have complained because Austen describes Marianne as getting over Willoughby and going forward to thrive as Mrs. Brandon. Johnson notes that if Marianne had in fact died of her illness, or if the younger Eliza has conveniently died, it would have been a standard, patriarchal sentimental solution to the "problem" of women disappointed in love, permitting the eternal preservation of loyalty to a man who has meanwhile gone his merry way. One wonders what bit of sickly sentimentality the critics of Austen's ending would like: Marianne renounces love and devotes herself to good works? Mrs. Willoughby conveniently dies? Or, pulling out all the stops: Eliza dies giving birth to a second, stillborn child fathered by another man (thus vindicating Willoughby's assertion that she wasn't really innocent, so his abandonment of her is less serious); Marianne successfully begs Colonel Brandon to let her rear her beloved Willoughy's child (a girl, naturally); Mrs Willoughby elopes with a lover (thus making Willoughby an injured party and allowing him to keep her dowry); after the divorce, Marianne and Willoughby marry, he is redeemed by her love, and she bears his heir. Faugh - I congratulate Johnson for cutting through such nonsense. I am somewhat less convinced by Johnson's analysis of Austen's portrayal of Henry Tilney in Northanger Abbey, but she builds a good enough case that I will have to reread the novel. I think she goes a bit off track in Mansfield Park. I think that Mrs. Norris was more incitor than adjutant to Sir Thomas' less admirable notions, alt

excellent polital reading of Jane Austin's books

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 25 years ago

I have enjoyed Jane Austin's books for a long time. Claudia Johnson helped me see how the books would be seen in Austin's time which increased my understanding and love of the books. As an example, Elizabeth Bennett is an unconventional heroine. Her laughter and energy was extremely unusual and was the sort of behavior that conservative fiction and propriety books of the time saw as improper. It was easy for me to miss this point since Elizabeth is the sort of person that we are expected to admire today.This book definately comes from a political and feminist viewpoint. At the time Austin was writing, the patriarchal society was considered an important part of England's defense against the ideas of the French Revolution. Johnson looks at how Austin examines and questions the assumptions of conservative thought while working within its accepted framework. She also highlights the irony that runs through Austin's work.I have read other critisms of Jane Austin's books as this is the one that has had the most to say to me.