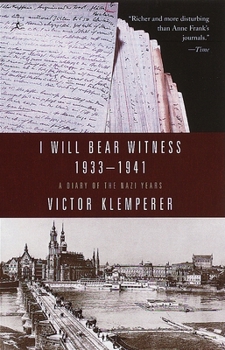

I Will Bear Witness, Volume 1: A Diary of the Nazi Years: 1933-1941

(Book #1 in the I Will Bear Witness Series)

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

The publication of Victor Klemperer's secret diaries brings to light one of the most extraordinary documents of the Nazi period. "In its cool, lucid style and power of observation," said The New York Times, "it is the best written, most evocative, most observant record of daily life in the Third Reich." I Will Bear Witness is a work of literature as well as a revelation of the day-by-day horror of the Nazi years. A Dresden Jew, a veteran of World War I, a man of letters and historian of great sophistication, Klemperer recognized the danger of Hitler as early as 1933. His diaries, written in secrecy, provide a vivid account of everyday life in Hitler's Germany. What makes this book so remarkable, aside from its literary distinction, is Klemperer's preoccupation with the thoughts and actions of ordinary Germans: Berger the greengrocer, who was given Klemperer's house ("anti-Hitlerist, but of course pleased at the good exchange"), the fishmonger, the baker, the much-visited dentist. All offer their thoughts and theories on the progress of the war: Will England hold out? Who listens to Goebbels? How much longer will it last? This symphony of voices is ordered by the brilliant, grumbling Klemperer, struggling to complete his work on eighteenth-century France while documenting the ever- tightening Nazi grip. He loses first his professorship and then his car, his phone, his house, even his typewriter, and is forced to move into a Jews' House (the last step before the camps), put his cat to death (Jews may not own pets), and suffer countless other indignities. Despite the danger his diaries would pose if discovered, Klemperer sees it as his duty to record events. "I continue to write," he notes in 1941 after a terrifying run-in with the police. "This is my heroics. I want to bear witness, precise witness, until the very end." When a neighbor remarks that, in his isolation, Klemperer will not be able to cover the main events of the war, he writes: "It's not the big things that are important, but the everyday life of tyranny, which may be forgotten. A thousand mosquito bites are worse than a blow on the head. I observe, I note, the mosquito bites." This book covers the years from 1933 to 1941. Volume Two, from 1941 to 1945, will be published in 1999.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0375753788

ISBN13:9780375753787

Release Date:November 1999

Publisher:Modern Library

Length:544 Pages

Weight:1.02 lbs.

Dimensions:1.2" x 5.2" x 8.0"

Customer Reviews

4 ratings

A Moving, Frightening View of Everyday Life in Nazi Germany

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

The most disarming and appealing feature of this tome is its slow and ineluctable building of suspense and empathy as World War I veteran Klemperer steadily weaves the day to day details of his life in 1930s Germany into a portrait of a rogue state moving irresistably down the path to tyranny and terror. The reader is sucked into the vortex of what it is like to live under such circumstances, where an aging Jewish professor who has built a life of purpose and meaning based on scholarship, hard work, and the belief in the rationalism of the state begins to understand that it will all unravel around him. You begin to experience how difficult and incomprehensible it must be for him, and empathize and worry for his fate as the building storm clouds of violent fascism fill the skies of 1930s Germany. As the days and weeks pass into months and years under the growing tyranny of National Socialism, Klemperer, married to an Aryan woman, increasingly finds solace and relief from the growing insanity swirling around him by concentrating on his academic writing, which he continues against all odds. As he faces an arbitrary enforced early retirement from his professorial duties, he also begins to take more time to enjoy simple pleasures with his wife, Eva, as they revel in long nature walks, the perils and pleasures of driving a second-hand car, and in watching the cinema. His refusal to submit to the progressively more invective growth of lies, invectives, and accusations of the Nazi regime build into a quiet resolve to resist in the way he knows best, by maintaining an intelligent, insightful, and careful witness to the everyday horrors perpetrated with malice and cunning on the Jews as the scapegoat for all of Germany's post-WWI social and economic woes. One stands by as we watch Victor and Eva systematically stripped of everything of meaning to them; their house, car, telephone, typewriter, even their beloved cat. While he understands all too well the dangers for him and his family, he consistently resists the increasingly strident pleas from family members for him to emigrate primarily because he identifies himself first and foremost as a German, and he refuses to abandon the Fatherland to the beastial likes of Hitler and the Nazis. One's sense of horror is magnified by his careful attention to the day to day details of living in the regime, the difficulties in finding socks, or clothing, or a cobbler, or vegetables, coffee, tobacco (both he and Eva are smokers), dealing with increasingly restrictive curfews, the ordeal and shame associated with the enforced wearing of the yellow star of David, the progressive acts of enforced segregation from the general populace, the occasional experiences at degradation at the hands of a youthful crowd of Hitler Youth. Yet there is great humanity evidenced here, both within the Jewish community and without it. The pathos of ordinary people caught in the web of a totalitarian

A diamond in the sandbox of Holocaust literature.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 25 years ago

My review refers to the german original edition of the Klemperer diaries from 1933-1945. In the german edition, the diaries are not published in two parts. It must be hard for the english reader to stop 1941 and wait. Klemperer wrote more than 5000 typoscript pages of diary during the nazi period. The german original edition with many cutbacks has more than 1800 pages (1933-1945), the english translation about 500 (1933-1941), so I expect more cutbacks in the english version - most likely around Klemperers language studies about LTI-lingua tertii imperii, the language of the 3. Reich - more interesting for german native speakers. For the english reader, which had yet only read the diary until 1941 I will give the warning, that the 1942 diary is really the most depressing one. The Klemperer diary is definitely the best book I ever read about the nazi-time. (second one: Hans Fallada, 1947: "Jeder stirbt für sich allein" (Everybody dies for himself), English title: ?)As a German I grew up with an endless amount of information, literature, books, documentations, discussions and history school lessons about the 3. Reich, but the most refer only to long known facts and their problem is, that they are written with the look of the survivers, the next generation or the history view which sorts and interprets the facts with the knowledge of the ending. I believe, that nobody can understand the system, who has not read "first-hand" impressions. The Klemperer diary is, what I always was looking for: An uncommented inside view to the all day life in germany in that days and the evolution of the unthinkable. A first-hand information about the terrorism not in the concentration camps, but in "normal" life. Klemperer shows on nearly every page of his book, how many germans didn't follow Hitler's antisemitic view. He noticed the meanings, conversations, wishes, anxiety of the german population and always wondered about the opinion of the majority - is it pro or contra Hitler? He noticed the endless list of restrictions for the jews - simple and little things, which are forgotten and pressed to the background by the horror of the concentration camps, but new for us today. He noticed, how people divide in heroes and opportunists. By reading about the nazi-time we always ask ourself "What would I have done?" Would I had helped the people who needed me despite of the danger of loosing my own life, or would I had taken care only for my own security.It's hard to imagine, that someone can register, analyse und document all this on an unbelievable level of quantity and quality under the circumstances of starving, illness, pressure work und humiliation. He wrote not only a diary, he wrote high level literature - espessially his description "Zelle 89" about his 8-day prisonary on a level like "Schachnovelle" (Chess novell) from Arnold Zweig (highly recommended!). Around Victor Klemperer his (and the readers) friends are murdered or m

KLEMPERER BRINGS TO LIFE NAZI HORRORS

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 26 years ago

I was terrified by the world that Victor Klemperer brings to life in " I Will Bear Witness ". The diary is a day by day account of a slow descent into the bowels of Hell. In the beginning the reader is pulled into Klemperers mostly mundane day to day life. Klemperer was a well respected and much published professor of Romance Languages at the University of Dresden. As well he was a decorated veteran of World War I. Slowly, starting with Hitlers rise to power in 1933, his entire world is turned inside out. Day by day the situation becomes more strained. Year by year the situation becomes more dangerous. But the brave hearted Klemperers stay on in Germany because they are German and can imagine no other life. I was greatly moved by the scenes that were brought to life by Klemperer. The description of the first household search they were subjected to caused goose bumps to run up my spine. In addition, the narrative of his 8 day imprisonment ( cell 89 ) is in my opinion a classic that will belongs to the ages. His ability to to draw a picture and capture the mood of a situation was truly amazing. I cannot say enough about the courage of the Klemperers as they fought everyday to hold onto their dignity, pride and finally their lives. Thanks to the skill and courage of Professor Klemperer I now have, in some small way, an idea of what the day to day horror of Nazi Germany was like for the persecuted.

Exciting, authentic, instructive - and immensely readable

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 26 years ago

I devoured the roughly 1500 pages of Victor Klemperer's diary in the German original in four consecutive days and nights. What grips one is the question how Klemperer, an identifiable Jew, could have survived the Third Reich in the face of the horrendous persecution of the Jews which his detailed diary shows closing in on him from all sides, and still be alive at the end of the Second World War viz the second volume of the book.What saved him was numerous favorable coincidents; so numerous indeed that they would appear improbabale in a work of fiction. On some occasions, his marriage to a Christian wife, a concert violinist, worked in his favor; on others, the courage of friends of the family, like the lady dentist, who, among other services, dared to hide Klemperer's completed diary pages in her home - despite the danger of Gestapo raids - and thus saved this document for posterity; at other points the leniency of an official helped (Klemperer's World-War-I-medal for bravery, or his renown as a Professor of Romance Philology tended to summon respect). Klemperer first suffered the pressures put on Jews in Nazi Germany to leave the country (that was the policy before The Second World War); roughly half of the German Jews did leave, but not Klemperer, who remained in his hometown, Dresden, because he could imagine no future for himself as a professer of Romance philology outside of Germany. Of course, the future stopped for him inside the country as well. Humiliations for Jews went from bad to worse as the War went on. Jews e.g. were no longer permitted to use a seat when they rode in a tram; they had to stand on the platform. On one occasion, when Klemperer was there, the tramdriver addressed him in a sympathetic fashion talk to openly in this moronic madness of a War." Since Jews were not permitted to use bomb shelters, the Klemperers were separated on the night of the worst air raid on Dresden in February 1945, because his wife got pulled into a shelter that he mustn't enter. By a near miracle the two found each other again at the border of the Elbe after the event, and his wife pulled the yellow star off him; he then survived the remainder of the war by posturing as an "Aryan" who lost all his identification I can tell you about the Third Reich, you won't be able to realize its real atmosphere. Life under that dictatorship is not transmittable by mere words." The sensation is that Klemperer's diaries do transmit that atmosphere, and in enormously precise words. The authenticity of the account arises from the peculiar perspective of a diarist, who, at any given point, possesses neither a privileged view of the future, nor easy hindsight-cleverness. An example is Klemperer's poignant account of the deportation of the Dresden Jews. Trembling he might be with the next transport, he was at pains to gather all available information, but with little success. The fate of the deported was strictly prohibited