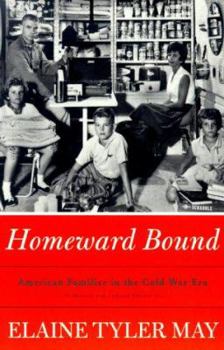

Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In the 1950s, the term "containment" referred to the foreign policy-driven containment of Communism and atomic proliferation. Yet in Homeward Bound May demonstrates that there was also a domestic... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0465030556

ISBN13:9780465030552

Release Date:February 1990

Publisher:Basic Books (AZ)

Length:269 Pages

Weight:0.98 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 6.1" x 9.4"

Related Subjects

20th Century Family Relationships Historical Study & Educational Resources History Marriage & Family Military Modern (16th-21st Centuries) Parenting & Relationships Political Science Politics & Government Politics & Social Sciences Social History Social Science Social Sciences SociologyCustomer Reviews

5 ratings

How the Hetero-normative, Racialized, Exclusive Suburban Family Ideal Became a Unifying Aspiration o

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

This work contends that there was an anomalous rise in "marriage, parenthood, and traditional gender roles" in the post-World War II United States that was pan-racial, pan-economic, pan-ethnic, and pan-regional. It attributes this to social constructions of home and family that responded to governmental policy aims and cold war anxieties. The work seeks unearth what, precisely, drives the anxieties behind these social formations and why they dramatically distort the post-World War II child bearing generation from the radicalism that preceded and proceeded them. May ascribes the geopolitical parlance of "containment" to the domestic cultural policies of the cold war United States. She asserts that the rhetoric and practice of the nuclear family served to contain subversive sexual and political behavior that might evoke contestation of gendered postwar consumerism, masculinist renderings of science qua exceptionalist prosperity, and endanger the social practices of unity, security, and stability that were understood to confer qualitative global advantage in the cold war. The author also engages the nuclear family as an aspiration that mobilized the majority of United States residents who were racially, economically, or otherwise excluded from its suburban actualization. The capacity of family to frame the intelligibility of "prosperity" for economic actors who were conferred unequal advantage is key, May suggests, to its postwar centrality in visions of an abundant and classless society. In this context, May's suburbs emerge as liminal spaces that both enact and resolve the contradictions between pre-and postwar culture, replacing the aspiration for equal condition with the condition of uniform aspiration, reifying romance as the mutual consent of liberal individuals yet encasing it in an exclusionary propertization of private life, and substituting ethnic kinship and working class consciousness that situated life in power with a homogenous whiteness that rendered power unintelligible. This is artfully demonstrated as the text traces the dispositions and cohesions of families from the New Deal era thru the early 1960s. The author's hybrid methodology combines statistical demographic data with qualitative analysis of cultural texts. May notes assiduously the key contradiction within this data; that while the imagery of suburban familial prosperity presented a level of prosperity that was realistically inaccessible for the majority of United States residents who encountered it, it nonetheless correlates with a strong voluntary entrance into the social formations of that aspiration that is evident across demographics. May goes as far as to entertain that the disconnect between the consumer aspirations of marginalized peoples and their social reality may have contributed to their motivation to pursue social change, also noting the strong political incentives to resolve visible racial inequality during the cold war. Indeed, the phenomenon throug

An intriguing premise

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

From the 1940s through the early 1960s, Americans married in greater numbers, at a younger age, and with a greater resistance to divorce than either their parents' or their children's generation. There occurred a remarkable dash into the domestic embrace of marriage and parenthood as American women abandoned their wartime jobs and joyfully rushed into the arms of returning World War II soldiers. But what provided the impetus for this yearning? The World War II generation was raised by parents who had come of age basking in the hedonistic pleasures of the Roaring Twenties following their return from the First World War. And their Baby-Boom counter-culture offspring were certainly no traditionalists. Both of these generations had in fact challenged conventional sexual norms while pushing the divorce rate up and the birth rate down. What then made the World War II generation different? What motivated them to embrace the roles of the traditional family with such desperate fervor and commitment? Homeward Bound is Elaine Tyler May's attempt to explain this sociological phenomenon by linking it to international politics. According to Tyler May, it was the Cold War that provided the impetus. Americans embraced domesticity during the early years of the Cold War because "the home seemed to offer a secure private nest removed from the dangers of the outside world." This mass retreat to the privacy and security of the home was in response to the twin threats of communist encroachment and potential nuclear attack by the Soviet Union. Specifically, Tyler May contends that the U.S. foreign policy of communist "containment" gave rise to the parallel societal view that the home could effectively contain the economic, sexual, and social desires of American women and men. To this end, the dynamics of the home required the rigid adherence to gender roles. Specifically, societal pressure induced women to marry young, give birth early and often, shun career aspirations, and stay home to raise their multiple offspring. Men, for their part, were expected to provide a steady and reliable stream of income for their growing families, regardless of the frustrating and stifling constraints imposed by their employers. Rather than painting a Norman Rockwell picture of comfortable domesticity, Tyler May chronicles a smoldering dissatisfaction with these rigid gender roles, causing guilt and resentment in the supposedly "happy days" world of the World War II generation. The book is divided into nine chapters covering a variety of topics relating to home life, career choices, sex, reproduction, and consumerism. It concludes with a chapter relating how and why the Baby Boom generation rebelled against their parent's obsession with security. Effective use is made of magazine articles, books (both popular and scholarly), newspaper reports, documentary films, government publications, and Hollywood movies. A revealing poll in whi

A landmark text in the field of American Studies

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

Elaine Tyler May's text "Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era", remains a classic in American Studies-and example of relevant, clear, well-written scholarship utilizing a variety of data to make a interesting and important case. This is not to say that the work has no weaknesses, but it remains in many ways an enduring, if somewhat superceded landmark in American cultural studies. Tyler May's central thesis of the book is that the foreign policy of the "containment" of communism, summarized and popularized by Secretary John Foster Dulles, paralleled the rise of a domestic politics of containment, where the home space became a way to contain the economic, sexual, and social desires of both women and men. Moreover, the construction of this home space necessitated the casting of gender, sexual, and social roles in rigorous, socially compulsory terms that effectively marginalized many people from ethnic, sexual, and ideological minorities. These roles, constructed through the politics of domestic containment, were held in majority American culture to be necessary to the social survival and maintenance of capitalism in the Cold War struggle against the Soviets. Women in particular, are focused on, as the strong, independent, single role models of the 1930's gave way to increased imagery of the married, safely domesticated woman, who were under heavy societal pressure to give birth and raise children. Men too were constrained by corporate superiors, and looked to home as the one place they could exercise full influence over their wives and children. Not everyone, of course, was happy with this. A number of surprising arguments are made and defended in this book as sub-theses to the greater point. Birth control achieved social acceptance quickly during this time, albeit "contained" in such a way as to officially promote family expansion and lower the marriage age. Fulfilled eroticism, albeit only in marriage, becomes a central point of majority discourse, to the point that women were counseled to pour more energy into their mates' fulfillment, sexual and otherwise, than the children of the household. (this is not to say those actual sexual attitudes and practices always reflected these images, as she points out on pg. 102) The Cold War demanded that the excesses of capitalism (in promoting huge differentials between rich and poor) had to be checked, lest communism breed and flourish in the nation's slums (147). Fewer African-American women went to college than white, but more of them graduated proportionately. May even shows that the so-called Baby Boom didn't start after the war, but rather in the early part of WWII, thus dispelling the common notion peace and affluence alone created the baby boom (these conditions also existed after WWI, but with no population boom.) Another excellent aspect of this study, besides nuancing the role of the Cold War, is the inclusion and careful use of quantitative data, the Kelly Lo

The Cold War's Home Front

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era (1988, New York: Basic Books, Inc., rev. and updated edn., 1999)In the introduction to this provocative study of an important facet of American social history during the Cold War, author Elaine Tyler May, who is Professor of American Studies and History at the University of Minnesota, asks: "Why did postwar Americans turn to marriage and parenthood with such enthusiasm and commitment?" Her answer is that, in an era when United States foreign policy attempted to "contain" the expansion of Communism, it was quite natural for white, middle-class Americans, the dominant segment of the society, to adopt the ideology May calls "domestic containment." According to May, Americans embraced domesticity during the early years of the Cold War because "the home seemed to offer a secure private nest removed from the dangers of the outside world." May proceeds to explain: ""Americans turned to the family as a bastion of safety in an insecure world." Furthermore, according to May: "Domestic containment was bolstered by a power political culture that rewarded its adherents and marginalized its detractors." The period from 1929 through 1945, which encompassed the Great Depression and World War II, had been an age of great anxiety. But May makes a convincing case that "the end of World War II brought a new sense of crisis" and that the postwar world was full of its own stresses. According to May, "the freedom of modern life seemed to undermine security." As a result, from the late 1940s and well into the 1960s, she writes that Americans "wanted secure jobs, secure homes, and secure marriages in a secure country." In both its international and domestic manifestations, according to May: "Containment was the key to security." Indeed, in May's view: "With security as the common thread, the cold war ideology and the domestic revival reinforced each other." According to May: "The ideological connections among early marriage, sexual containment, and traditional gender roles merged in the context of the cold war," and "much of the postwar social science literature connected the functions of the family directly to the cold war." According to May: "Strong families required two essential ingredients: sexual restraint outside marriage and traditional gender roles in marriage." May writes: "The sexual containment ideology was rooted in widely-accepted gender roles that defined men as breadwinners and women as mothers." It is critical to May's thesis that "marriage itself symbolized a refuge against danger." According to May, most Americans believed that "a successful marriage depended on a committed partnership between a successful breadwinner and his helpmate."That belief was reinforced by a Cold War-era study funded by the Ford Foundation and conducted by two Harvard sociologists which concluded that the key to successful families "was stable homes in

a must-read for women of all ages!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 25 years ago

Being a gen-xer, this book, revealed so much about my parents and grandparents. Elaine Tyler May tells the stories of families, and women, in particular, during the cold war from a perspective that really grabs the attention of the reader. I never would have read a book like this, had it not been required for a political history class I am involved in at college, however, it was one text that I would seriously enjoy reading again. (For most college students this says it all!!) This was a great book!!!