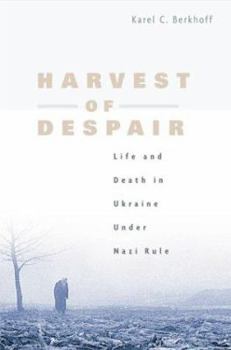

Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine Under Nazi Rule

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

If I find a Ukrainian who is worthy of sitting at the same table with me, I must have him shot, declared Nazi commissar Erich Koch. To the Nazi leaders, the Ukrainians were Untermenschen - subhumans. But the rich land was deemed prime territory for Lebensraum expansion. Once the Germans rid the country of Jews, Roma, and Bolsheviks, the Ukrainians would be used to harvest the land for the master race. Karel Berkhoff provides a searing portrait of life in the Third Reich's largest colony. Under the Nazis, a blend of German nationalism, anti-Semitism, and racist notions about the Slavs produced a reign of terror and genocide. But it is impossible to understand fully Ukraine's response to this assault without addressing the impact of decades of repressive Soviet rule. Berkhoff shows how a pervasive Soviet mentality worked against solidarity, which helps explain why the vast majority of the population did not resist the Germans. more nuanced way issues of collaboration and local anti-Semitism. Berkhoff offers a multifaceted discussion that includes the brutal nature of the Nazi administration; the genocide of the Jews and Roma; the deliberate starving of Kiev; mass deportations within and beyond Ukraine; the role of ethnic Germans; religion and national culture; partisans and the German response; and the desperate struggle to stay alive. Harvest of Despair is a gripping depiction of ordinary people trying to survive extraordinary events.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0674013131

ISBN13:9780674013131

Release Date:April 2004

Publisher:Belknap Press

Length:463 Pages

Weight:1.70 lbs.

Dimensions:1.6" x 6.4" x 9.3"

Customer Reviews

3 ratings

Ukrainians as WWII Victims and Victimizers; OUN-UPA Genocide of Poles

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

This Dutch historian discusses such relatively-familiar events as the Soviet famine-genocide of Ukrainians, the scorched-earth policies of both the retreating Soviets and Germans, deportations of Ukrainians for forced labor, imposed Nazi hunger (p. 45), etc. The German occupation cost the lives of at least 1 million people of all nationalities in the Reichskommissariat Ukraine alone. (p. 307). As for Ukrainians and Jews, "Both factions of the OUN were anti-Semitic themselves, and wartime documents with regard to leading Banderites show that during the German invasion, they wanted the Jews, or at least Jewish males, killed, and that they were willing to participate in the process." (p. 83, 348; see also p. 288, 429). Berkhoff then elaborates on the little-known OUN-UPA genocide of Poles (pp. 286-300). Soviet partisan leader Strokach said that the UPA has, "...the aim of totally destroying the Poles in Ukraine." (p. 287, 428). Berkhoff also quotes a fascinating letter, by SB-leader Vasyl Makar, who describes the "action to destroy the Poles" which had "not produced the expected results". (p. 287, 428). What further proof is needed for genocide? The fact that all Poles weren't killed wasn't from the UPA not trying! Unfortunately, Berkhoff cites secondary sources that grossly underestimate the Polish victims. (p. 286, 427). In actuality, detailed village-by-village compilations (Siemaszko and Siemaszko for Volyn, and Komanski for the Tarnopol area) alone record over 45,000 Polish deaths. Owing to the fact that their coverage is spotty, and then only applicable to a fraction of the relevant overall geographic area, the actual number of Poles murdered by the OUN-UPA genocide is easily in the 150,000-300,000 range. Berkhoff also errs in implying that Taras Czuprynka (Roman Shukhevych) ended the killings. (pp. 298-299). To the contrary, there exists a document in which Skukhevych called for the speeding-up of the destruction of Polish villages prior to the arrival of the Red Army. Berkhoff is perceptive in realizing that the Polish killing of Ukrainians near Zamosc-Kholm (Chelm), often used as a pretext for the OUN-UPA genocide of Poles, will not do. It was neither indiscriminate, nor remotely commensurate, nor even "initial". He writes: "Here too, the complaints of the main aggressor had some validity. Polish underground activists had been murdering Ukrainian leading figures in the Lublin district since at least May 1942, and Polish partisans (which had grown in number after a Nazi campaign to expel peasants) assaulted police stations, which were manned by Ukrainians. But Ukrainian policemen there had been killing Poles, and overall the events were more complex than the Banderites would like to admit." (p. 293). Berkhoff also understands the fact that Volhynian Poles siding with Germans against Ukrainians was a response to, not provocation of, the OUN-UPA genocide against Poles, and that it seemed much larger than it actually was because of the i

Harvest of Despair

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Harvest of Despair; Life and Death in Ukraine Under Nazi Rule Karel Berkhoff Belknap Press The history of Ukraine is a tangled web of invasion, exploitation, and, despite it all, hope. As you drive through the Ukrainian countryside, you can see monuments to the "Great Patriotic War" and most major cities have more than one memorial to the Soviet citizens who defended their homeland against the Nazi invaders who planned on re-making Ukraine into a German agricultural colony. Karel Berkhoff's Harvest of Despair is an attempt to look at the Nazi plans for the occupied Ukraine and Ukrainian reaction to them. In every sense, the Ukrainian people were caught between a rock and a hard place- the two choices left to them were Hitler's Nazis or the Stalin's Soviet Union. Berkhoff's narrative places the Ukrainian choices into context, explaining why the two choices were variously chosen, and why, in the end, both proved inadequate. When the Nazi's first invaded Ukraine in June, 1941, many welcomed the Germans as liberators. Indeed, the treatment that the Ukrainian peasantry received under Stalin's collectivization plan and engineered famine would make almost any alternative seem attractive. Coupled with the lack of good information about Nazi rule in other parts of Europe and the almost total collapse of Soviet defenses, Germany seemed a ray of hope. That hope was soon dashed as the nature of Nazi rule manifested itself. The Nazis planned on making Ukraine an agricultural colony to be populated by "Germanic" people. The Slavic Ukrainian people, by definition inferior according to Nazi ideology, were at best an impediment to these plans. The Ukrainians were tolerated insomuch as there were economically useful to the Nazi regime. Peasants, who produced food in abundance, were allowed to survive, albeit with the ever-present danger of forced labor in Germany or summary execution. City dwellers, especially those who were not deemed economically useful were expected to starve, which they did by the thousands. The brutality of the Nazi regime, whether revealed in the mass execution of the local Jewish populations, the summary executions under the most flimsy of pretexts, or the conditions suffered by those in forced labor in Germany, soon soured the Ukrainians to the prospect of their "liberation." But the Ukrainians found themselves as powerless in the face of Nazi power as they did under the Soviets. That there was resistance at all, be it evading work to sheltering Jews, is remarkable in a society where resistance to authority was swiftly and severely punished, regardless of the regime. Berkhoff organized Harvest of Despair thematically, which allows the reader to "spiral" their knowledge into a coherent whole after reading the entire work, while allowing each chapter to stand alone if necessary. One item that would have been useful to the general reader would be an explanation of the German military and civilian terms in greater detail. Co

Sheds light, and spares no one

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

This beautifully researched book should help substitute some well-documented scholarship for the acrimonious debates that have raged since the conclusion of World War II. Some of these debates upon which the book sheds light: Was Ukraine victim of Nazi aggression or its collaborator? Did Eastern and Western Ukraine experience cardinally different occupation policies? Did Eastern and Western Ukrainians both welcome the German invasion of 1941 and for what reasons? Did the two parts of the country develop different defense mechanisms against German policies? How did the common people react to initial promises, and how did they react later to the actual policies of exploitation and starvation of Ukrainian urban centers? Did the two factions of the OUN develop different strategies of dealing with the occupation? Did Eastern Ukrainians welcome OUN workers to mitigate Nazi excesses? Did the differing schools of thought among the Nazi hierarchy itself - that is, Koch versus Rosenberg, et al - in dealing with Ukrainians have much impact? Did the de facto on-the-ground changes in policy come too late? Much in the book is especially relevant today - as the debates flare up again - and could, for example, help explain the radically different views Western Ukrainians and Eastern Ukrainians take toward the OUN and the UPA. I highly recommend this fair and objective book, and I must admit that as Ukrainian myself, this book spares no sensibilities and at times the truth hurts - all the more reason, I believe, to read the book.