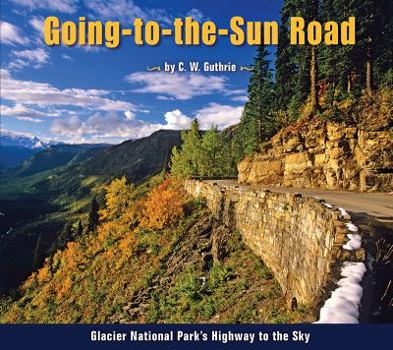

Going to the Sun Road: Glacier National Park's Highway to the Sky

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Traveling Glacier National Park?s Going-to-the-Sun Road is an experience like no other. Laborers toiled for nearly 20 years to complete the 50-mile road that winds an impossible route through the... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:1560373350

ISBN13:9781560373353

Release Date:May 2006

Publisher:Farcountry Press

Length:70 Pages

Weight:0.71 lbs.

Dimensions:0.2" x 9.1" x 8.1"

Customer Reviews

1 rating

Going-to-the-Sun Road

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

There are a few people who become terrified going over a lofty highway cut into a rocky cliff. They may be excused for not wanting to cross Glacier National Park on the Going-to-the-Sun Highway. For everyone else, it is an experience not to be missed. The mountain scenery is unsurpassed. It is as close to the wild that one gets while traveling a paved highway. The hikes, whether long or short, are immensely rewarding. Geologists go wild over the fact that an overthrust gave us massive sedimentary mountains on top of younger formations. The wildflowers are spectacular; as are the waterfalls and lakes. The naturalists are wonderfully helpful and their presentations always interesting. On top of all that, the highway is an engineering marvel. I crossed Glacier National Park for the first time in 1962. Since then, I have seen it throughout the approximately four month season when snow does not block the Going-to-the-Sun. Each trip I see different aspects of Glacier and become more fascinated with its natural history. I enjoy noticing the changes that have occurred. Even the melting glaciers and increasing wildfire damage brought on by global warming reveal new and interesting aspects. Always there is The Road. Indeed, its very existence is an amazing thing. The story of its construction is fascinating. This little book by C.W. Guthrie tells the story in words and pictures. She does it succinctly and thoroughly. She sets the historical background and follows the construction throughout the highway's 50 mile length. Its birth dates from 1911 to 1933 and it continues to change year by year. The initial sections were built with the muscles of humans, horses, and mules. By the time of the final dedication July 15, 1933, caterpillars, steam shovels, trucks, and gasoline launches supplemented the human labor. The first cars over the road drove on gravel; not until 1952 was the highway completely paved. The roadway goes through tunnels and rides across stone arches. In places, great stone buttresses hold it against the mountainside. The maximum grade is six percent and it climbs to 6,646 feet at Logan Pass where it crosses the Continental Divide. The designers worked to make the road blend unobtrusively into its natural setting. They succeeded. That in itself is an amazing accomplishment. Part of the story of Going-to-the-Sun is the tourists. The parking facilities and necessary amenities allowing people to reach the attractions, the shuttles and busses for those who choose not to drive, and the provisions to accommodate the diverse crowd of sightseers, hikers, and campers who use the park are all part of the highway's history and future. Guthrie briefly introduces us to the continuing story of the Going-to-the-Sun Highway. Total construction costs from 1911 through 1934 were $2.4 million dollars. Today, the annual maintenance budget exceeds that number and fails to keep up. Getting the road open each spring, usually by th