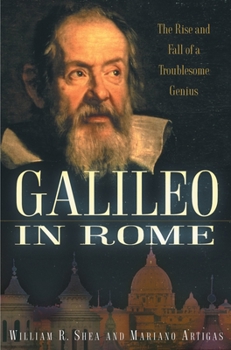

Galileo in Rome: The Rise and Fall of a Troublesome Genius

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Galileo's trial by the Inquisition is one of the most dramatic incidents in the history of science and religion. Today, we tend to see this event in black and white--Galileo all white, the Church all black. Galileo in Rome presents a much more nuanced account of Galileo's relationship with Rome.

The book offers a fascinating account of the six trips Galileo made to Rome, from his first visit at age 23, as an unemployed mathematician, to his final...

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0195165985

ISBN13:9780195165982

Release Date:September 2003

Publisher:Oxford University Press, USA

Length:226 Pages

Weight:1.30 lbs.

Dimensions:1.0" x 9.3" x 6.1"

Related Subjects

16th Century Biographical Biographies Biographies & History Biography & History Christian Books & Bibles Church History Churches & Church Leadership History & Philosophy Modern (16th-21st Centuries) Professionals & Academics Religion Religion & Spirituality Religious Studies Science Science & Math Science & Religion Science & Scientists Science & Technology Scientists TechnologyCustomer Reviews

5 ratings

A Fine Introduction to a Famous Controversy

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

The trial of Galileo for endorsing the Copernican idea of a sun-centered cosmos is of course infamous in the conflict of religion and science. In all Galileo made six visits to Rome to find work and sponsor his ideas. He became quite famous, and also quite controversial in his day. What is less known is the context of why Galileo's ideas were so spectacular (and also, why some of them were so wrong). Shea and Artiagas have done a fine job portraying the life of Galileo Galilei, based around the six visits he made to Rome. They fill in the spaces between with enough biographical sketches and discussion of his ideas to give the reader a very satisfactory idea of the importance and incendiary nature of heliocentric ideas in early 17th century Italy. Definitely recommended for those interested in the development to scientific ideas in a religiously dominated climate.

The Finest in Galileo Scholarship that Reads like a Novel

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

I have been interested in the Galileo affair for some years and I have read some great and difficult scholarly works about the case, such as Galileo, Science and the Church by Jerome J. Langford, Galileo, Bellarmine and the Bible by Richard Blackwell and Galileo: For Copernicanism and for the Church by Annibale Fantoli and also the more readable, but well-researched, fascinating and well-written Galileo's Daughter by Dava Sobel . All these readings have deepened my understanding of the issues involved in the affair, but have increased my hunger to know more. This lead me to read (with a great deal of skepticism, I may say) Galileo in Rome: The Rise and Fall of a Troublesome Genius. After reading this work, I must agree with Stephen M. Barr, theoretical particle physicist at the Bartol Research Institute of the University of Delaware and author of Modern Physics and Ancient Faith, that Galileo in Rome "represents the finest in modern Galileo scholarship." What I like most about this work is the combination of high quality scholarship with an excellent narrative strategy. The book tells the story of the founder of modern science from the perspective of his six visits to Rome. At the beginning he is a twenty- three- years old job seeker, at the end he is an old man sentenced to house arrest by the Inquisition. This book is powerful drama. It truly reads like a novel, but the tone is dispassionate and objective. Most importantly, it offers a balanced account that portraits the affair in all its complexity. Nevertheless, the trial was a tragic mistake and could have been avoided. It caused great damage to the Church and Galileo suffered a lot because of it.

The difficulty of incorporating scientific thought into established orthodoxy.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Recognized as the father of modern science for his study of physics and astronomy, Galileo's adherence to the Copernican theory of heliocentrism might not have been so problematic had it not been for his personality and misreading of Vatican politics. As it was he felt justified in printing his treatise Dialogue contrary to the church's admonition against his teaching of the theory. It is indicative of Galileo's scholarship and reputation that few of the volumes were handed back to authorities when the Dialogue was banned and Galileo was permitted to serve his sentence under house arrest. Galileo's six trips to Rome began as a young man seeking employment and culminated with his hearings before the Holy Office forty-six years later when he admitted to "having violated an injunction not to discuss Copernicansim." (194) The author's use Galileo's letters, Papal records, newly discovered documents, and historical references to place the story in context. As it unfolds the difficulty of incorporating scientific thought into established orthodoxy is shown at the very conception of science. What becomes clear is that a discovery, to be accepted, has to have a welcome mat and the structure of society does not always provide one. Galileo had to operate within an ecclesiastic framework not in tune with his views. While Galileo had many supporters, his opponents, whom he often accused of being ignorant, were powerful adversaries. It did not necessarily matter whether objections were valid or not as long as they adhered to tradition. Another problem for science, is demonstrated by Galileo's use and improvement of the telescope. The power of the scope was increased twenty times and objects could be properly focused. Galileo demonstrated the telescope in social settings to impress distinguished guests with a close-up view of Rome and the stars. However his critics did not always understand the telescope's potential because "impatient and shortsighted philosophers often saw a blurred image that confirmed their prejudices." (41) Within the scientific community new devices do not necessarily lead to conformity of opinion. Utilizing the telescope, Galileo was able to observe Jupiter with its satellite moons revolving around the sun in a Copernican system. That and the discovery of sunspots overturned Aristotelian perfection of the universe. Even though Galileo and the Jesuit professor from Germany, Christopher Scheiner, both observed the same spots, they came to different conclusions: Scheiner to buttress Aristotelian immutability by declaring the spots were moons and Galileo by using the sun spots to show the Sun's rotation on its axis. There is another point to be made from reading Shea and Artigas' book on Galileo. All his life Galileo held to his belief of tidal theory "as his decisive argument for the motion of earth." (123). Here the recognized father of modern science is holding resolutely to an idea contrary to basic observation of seaman that

HELIOCENTRICITY v. THE CHURCH

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Early 17th Century Rome. Any book that is published must first be reviewed and revised by the Catholic Church. The Church still stings from Martin Luther's 95 Theses, and King Henry VIII's secession. A Papal Conclave is disrupted by three Cardinals dying whilst Rome is in the grip of a malaria outbreak. Bubonic Plague rears its ugly head after close to 300 years. The Pope peppers his Cardinal enclave with relatives. The Pope is not only a spiritual leader, but also the mayor of Rome, trying to administrate a bustling city while also nurturing the world's flock. And not all the Cardinals support the Pope, either (and he knows it). Enter Galileo, who argues that the Earth is NOT the center of the universe; the sun is. The establishment likes his telescope, but not what he sees through it. Galileo will not abide superstition; he believes heliocentricity is a fact, and he's damned and determined to make sure everyone else believes it too. This idea crashes head-on with long-held beliefs, and the Catholic Church is not about to tolerate another compromise. After five journeys to Rome to argue his case, spread out over decades, Galileo is at last subpoenaed by the Tribunal of the Inquisition, where confession is mandatory. The only question is--should the defendant be put to death . . . or merely imprisoned? Enter this world where free thinking might put you in irons, where paranoia is the rule, where whispers can kill. These learned men, the authors, have left no stone unturned in exploring the role and effect of Galileo's scientific endeavors. At the time, he was an extremely likable man--full of anecdotes, well-read, he could make the ladies laugh--but no one dreamed he would become the father of modern science, as he is regarded today. But he was also a tragic man, beset with lifelong illness, the loss of friends and relatives to disease, and the misery of isolation for his beliefs. And he agonized over the fact that the Church questioned his faith in God. This book can be dry; it can overload you with Italian names--it can fill you with righteous anger--but it can never bore you. For all ye lovers of truth, of justice, of history, even of Catholicism, I unreservedly recommend this book.

The Galileo of History

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

I would recommend this book for anyone interested in understanding the Galileo affair as an historical event and not simply as the stereotype of obscurantist religion fearing the truths of science. Built around Galileo's six trips to Rome, the authors give a lucid explanation of Galileo's life and work. Galileo's is ever more successful as a scientist and ever more eager to vanquish those who disagreed with him. While clearly a scientific genius, he claimed theories to be true without ever having physical proof. He insisted, falsely, that the tides were caused by the earth's rotation and then used the fact of the tides to argue for the Copernican thesis that the earth and not the heavens was in motion. When certain theologians objected that his theory seemed contrary to scripture, he entered, with no expertise, into a theological discussion on the proper mode of interpreting scripture. Unfortunately this intemperance in debate led finally to Galileo's "trial" and house arrest. At the same time, the theologians are presented as a mixed lot, some opposing Galileo with an irrational zeal, others soberly weighing the evidence he proposed and so insisting that he treat his theory as a hypothesis and not as proven fact. The authors present the Church's position with some sympathy: it seemed imprudent to change the more obvious understanding of scripture without proof for the scientific theory that undermined it.The book's prose is plain, but always clear and readable. The tone is dispassionate and objective. The authors, both serious scholars in the field, have clearly done their homework (but mercifully use endnotes) and present a balanced account. This book may not change your view of Galileo or the Church, but it will certainly leave you much better informed about the facts of the case. Given the importance of understanding science and religion, this is no small matter.