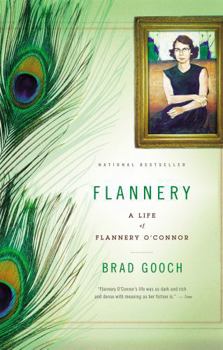

Flannery: A Life of Flannery O'Connor

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

A "passionate and smart" biography and the definitive account of literary genius Flannery O'Connor's life (Los Angeles Times), perfect for viewers of Ethan Hawke's Wildcat. The landscape of American literature was fundamentally changed when Flannery O'Connor stepped onto the scene with her first published book, Wise Blood, in 1952. Her fierce, sometimes comic novels and stories reflected the darkly funny, vibrant,...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0316018996

ISBN13:9780316018999

Release Date:March 2010

Publisher:Back Bay Books

Length:464 Pages

Weight:1.07 lbs.

Dimensions:1.3" x 5.4" x 8.2"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

"hermit novelist"

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Mary Flannery O'Connor (1925-1964) published only two novels--Wise Blood in 1952, and The Violent Bear It Away in 1960, and two collections of short stories--A Good Man Is Hard to Find and Other Stories in 1955 and the posthumous Everything That Rises Must Converge in 1965. That output was more than enough for her short life to cast a long shadow across the literary landscape, evidenced by the 195 doctoral dissertations and seventy book length studies of her work. Gooch has written the first major biography of O'Connor since she died, adding to our fund of knowledge from letters that were newly released in 2007 and countless interviews with O'Connor's friends, classmates, colleagues, publishers, and critics. O'Connor cut an odd figure. From her earliest years as an only child, she was always socially awkward, deeply introverted, and colorfully eccentric. She laced her coffee with coke, enjoyed racist jokes, never married, and collected exotic birds (especially her beloved peacocks). A deeply pious Catholic, she lived in the Baptist south. When she entered college she intended to be a political cartoonist but found her calling at the Iowa Writer's Workshop. After leaving Georgia for Iowa, New York City and Connecticut, her diagnosis of lupus at age twenty-six (the same disease that killed her father when he was forty-five) returned her back to isolation on the 550-acre working dairy farm in rural Georgia run by her widowed mother, from which isolation she wrote powerfully disturbing fiction about human nature. O'Connor was also an exceptionally disciplined writer, establishing early on an inviolable and lifelong regimen of writing three pages a day every morning. Most of all, O'Connor was one of the most important Christian writers of the last century or more. She attended daily mass most of her adult life, and described herself as "a thirteenth century Christian" and "hermit novelist." Indeed, she read broadly and deeply in Aquinas and other theologians. For her, the craft of her art--good stories well told--was an end in itself and a sign of God's grace. The content of her fiction was also her confession of faith: "My subject in fiction is the action of grace in territory largely held by the devil." To those who complained about her grotesque and deeply flawed characters, she insisted that "there is nothing harder or less sentimental than Christian realism," and that "to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost blind you draw large and startling figures." For the most part Gooch connects the events of O'Connor's life with what he perceives as the autobiographical aspects of her fiction. He acknowledges but does not treat in depth O'Connor's cultural racism (she once refused a visit by James Baldwin) or tense relationship with her overbearing mother who ran the farm as a savvy business woman. I also wish that Gooch had included some of O'Connor's extensive art work among the 16 black and white photos.

Fifty-six Years to Go

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Flannery O'Connor, as Brad Gooch's new biography makes clear, was one of a kind. His descriptions of Depression era Georgia remind us just how far the rural South, where she grew up, was from the American mainstream, and how rich the minefield for eccentric characters. O'Connor herself might have been one. An only child, born to landed Irish Catholics in Savannah, she developed an early liking for domestic fowl and became famous for teaching a chicken to walk backwards. If you're a fan of her work, and I am, the only thing startling about the story is that when the chicken balked she didn't attack to Pathe newsmen come to record this feat. In a milieu where girls of her social class were expected to be well-mannered and lady-like above all, O'Connor struggled to be herself. Largely, she succeeded, but she realized her need to get away to develop what some people recognized early on as artistic genius. Gooch, an English professor and author, is a disciplined biographer, careful in his research and in his interpretations of it. He's also a competent guide to the Catholic theology that informed O'Connor's work and comforted her throughout her short, brutal life. O'Connor's faith was a link to many of her literary contemporaries--Robert Lowell, Walker Percy, Robert and Sally Fitzgerald, Katherine Ann Porter among them. Sadly, it also restrained her ideas about social justice; she rejected Dorothy Day, for example, and declined to entertain James Baldwin in Georgia. But she did embrace Teilhard de Chardin and Thomas Merton. Two tricky subjects emerge--O'Connor's sexuality and her attitudes about race. Gooch, who has written about his emergence as a gay man, handles the ambiguity around O'Connor's sexual preferences and behavior well, sharing what intimates have said but resisting categorizing O'Connor, something she refused to do. Her racial attitudes are more troubling, and this reader wished he had interviewed African-Americans in the communities where she grew up. Savannah, Atlanta and Milledgeville may have been segregated, but blacks were acutely aware of their white neighbors and could have offered insights Gooch neglects. Instead we learn of her more liberal friends' horror at her racist speech, which was, at least, more moderate than her mother's. O'Connor,who died in 1965, has been dead longer than the 39 years she lived. She always said she wasn't trying to be "topical," and that she'd trade 100 contemporary readers for just one a hundred years in the future. Gooch's book is a step toward making that wish come true.

A Good Bio is (Not) Hard to Find

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

I've loved Flannery O'Connor since I was in college; back then, I read a story a night before I went to bed. I tried to turn my friends onto her but to no avail, even despite my overenthusiastic description of "A Good Man is Hard to Find" as the worst family vacation story ever. It was then that I found an essay on O'Connor by Alice Walker that had originally been published in "Ms." magazine in the 70s. It made me curious about who O'Connor was but despite the descriptions of her as a Southern Catholic writer who had lupus and loved peacocks, I knew very little. Only last summer I was looking through the holdings at the local library and was disappointed at the lack of biographical works on O'Connor. And six months later, here we are with Brad Gooch's brand new biography. It's astonishing to me that this is the first major biography for such a major and influential twentieth-century writer. (As compared to the few biographies that were part of a series on major authors that were best used as references for students - but what about the rest of us?) O'Connor died in 1964 so this book has been a long time coming and it's been worth the wait. Gooch, whose biography of the poet Frank O'Hara (another subject with a life cut short) was a great achievement, has written an accessible and thoroughly entertaining work on the short life but indelible career of one of my favorite authors. The background on O'Connor and her writing is invaluable as is the insight into how many characters in her stories were inspired by her own mother, Regina including the memorable, doomed Mrs. May from "Greenleaf." Gooch gives us more insight into the "Southern Catholic writer," showing us the fascinating woman whose knowledge of her impending fate spurred her into producing some amazing fiction. Has O'Connor's unique style ever, EVER been matched? While this is a small thing to note, the book has a beautifully designed dust jacket. I am grateful to Gooch for writing this book, and for doing it so well.

Parsing the Details of an Extraordinary Ordinary Life

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Brad Gooch's "Flannery" passes the test fundamental test for excellence in a biography: when the book is finished the reader fundamentally understands the subject of the book in a way he or she did not before. Like many readers of my generation (graduated high school 1978), I had a good introduction to Miss O'Connor's short stories - sprung on us with relish by an English teacher from the South. Compared with most of the other materials we were covering those stories were shocking to say the least. Over the years I wondered what kind of life the author must have led to produce those stories - both the hard edges and the evident spirtuality they contained. We (those outside the literary world) did not know much about O'Connor in that era - only that she was a serious Roman Catholic and had died young after a long fight with Lupus. Brad Gooch's exhaustive research surely paid off as he fills in the details - about her family life, her medical conditions, her spirtual life and both the joys and difficulties of her writing. Perhaps what surprised me the most were the legion of friends and fans this very unusual women attracted living, as she did, a rather quiet life in a generally quiet place. Professor Gooch provides his readers with a very vivid portrait of Miss O'Connor's struggles - and how her faith and her sickness found their way into her works. As a Roman Catholic myself, reflecting on Miss O'Connor's strong faith in the face of her difficulties through this biography seemed very fitting for Lent. I suspect, based upon the lengthy acknowledgements and sources cited (these should certainly be read) that Professor Gooch could have written a far longer book. I am glad he did not. The size, scope and pacing were all excellent. I commend this biography to any one who ever wondered about Flannery O'Connor or, indeed, the American literary scene after the War.

"I Farm From The Rocking Chair"

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

A very long time ago in a graduate English course I read all the fiction of Flannery O'Connor and have not read her since. Brad Gooch's new biography FLANNERY: A LIFE OF FLANNERY O'CONNOR convinced me that I should reread her, and that is no small compliment for a biographer. Too often a pedestrian account of some favorite writer's life will leave me unmoved--I have yet to finish a biography of Emily Dickinson although I have tried to read several-- although that is certainly not the case with Mr. Gooch. From the opening paragraph of his telling of the five-year-old Mary Flannery's (she was called both names as a child) visit by a Pathe newsreel company camerman for the purpose of filming her bantam chicken walking backwards to the sad account of the death and funeral of one of America's most celebrated writers, the story seldom drags. Born on March 25, 1925 in Savannah of Irish Catholic parents, Edward and Regina O'Connor, Flannery lived there until she was thirteen when the family moved to Milledgeville, Georgia. Her beloved father died in 1941 at the young age of 45 of lupus, the disease that would eventually kill Flannery. She attended Georgia State College for Women in Milledgeville, then the Iowa Writers' Workshop and Yaddo, the artists' colony in upstate New York. Stricken with lupus at 25, O'Connor returned to Milledgeville and lived there for the rest of her too short life-- she died at the age of 39--with her mother on a dairy farm surrounded by peacocks and other animals as well as both black and white farmworkers, some of whom would become models for the "freaks" she wrote about in her fiction. O'Connor left the farm on occasion to make speeches and visit friends and would travel out of the country only once, on a trip to Europe and specifically Lourdes, calling herself an accidental pilgrim. She opined about the trip with too many stops in too many places: "By my calculations we should see more airports than shrines." Mr. Gooch has done exhaustive research; there are voluminous notes at the end of the book that are listed chronologically from page 1 to the end of the biography rather than by starting over with each chapter, making for ease in using the notes. He is seeped in O'Connor's stories as well as he often points out incidents and people in her life that show up in her fiction. Mr. Gooch also quotes liberally from both O'Connor's reviews and essays. Any biographer worth reading would have to tackle both race and religion and Mr. Gooch does. Describing herself as a Thirteenth Century Catholic, O'Connor was a woman of deep faith and attended mass daily when able and read many Catholic writers including Thomas Merton and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. Furthermore, many of her close friends including Robert Lowell and Robert and Sally Fitzgerald were Catholic as well. Unfortunately O'Connor did not share the progressive attitude about race of many in the Catholic Church. She was known to have used the "N" word in private, told ra