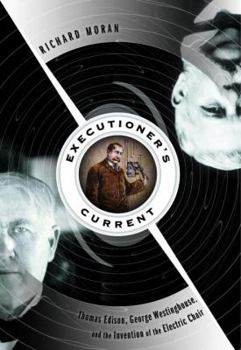

Executioner's Current: Thomas Edison, George Westinghouse, and the Invention of the Electric Chair

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

A "fascinating and provocative" story (The Washington Post) of high stakes competition between two titans that shows how the electric chair developed through an effort by one nineteenth-century... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0375410597

ISBN13:9780375410598

Release Date:October 2002

Publisher:Alfred A. Knopf

Length:271 Pages

Weight:1.35 lbs.

Dimensions:1.1" x 6.5" x 9.5"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Interesting and informative

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

Executioner's current is a fascinating look at the invention of the electric chair, the controversy surrounding the first death penalty case involving the chair and the fight for commercial supremacy between the Westinghouse Company and the Edison Electric Company in the area of electricity distribution. Richard Moran ties all of these elements together in a quick reading, well referenced analysis. The book also covers the evolution of the death penalty, the definition of cruel and unusual punishment and the trial of William Kemmler, the first man ever sentenced and put to death by electricity in the United States. Mr. Moran skillfully weaves a small array of facts, statutes, opinions and brutal clashes between Edison and Westinghouse into a compelling history that reads more like a well written novel than a work of straight history.

Well-Written and Thorough

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

This is a good book. In addition to being very clearly written in a very engaging style, the author discusses just about all aspects of the development and use of the electric chair: technology of the times, effects of electricity on the human body, legal and political aspects of executing condemned criminals using electricity, related sociological matters, even the life, trial and details of the execution of the chair's first official customer. Naturally, the war between Edison and Westinghouse, i.e., DC vs AC, plays a most prominent role in this exciting saga; in particular, the "efforts" in determining which is deadlier: DC or AC. Highly recommended!

A must read for all who support the death penalty

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

While this book may not be enough to push you over the line to rejecting the death penalty, it will certainly make you think about it. A very enticing read, the book touches upon complicated legal entanglements and medical issues without becoming too hard to understand. However, for those with little interest in criminal justice (or the mechanics of electricity), this is probably not a wise choice.This book starts out being about criminal William Kemmler and the first case in which the electric chair was used. However, as the story progresses, it becomes more and more a tale of Thomas Edison (America's prized inventor and advocate of direct current) and his primary competitor George Westinghouse, who utalizes alternating current. Moran paints a dark picture of Edison, who will seemingly stop at nothing to slanderize Westinghouse by encouraging use of alternating currents for electrocution. This proves a major problem for Westinghouse, because in having his current branded an 'executioner's current', something dangerous to the public and only suited for providing death, he could lose valuable customers. In this work, Moran's primary goal is to show how the invention and enactment of the electric chair as America's primary method of execution was chiefly motivated not by a desire to improve the humaneness of execution, but by corporate greed. When Edison and his lackey Harold Brown (another electrician) propetuate propaganda about alternating current as 'the best current for electrocutions due to its deadly nature', they are not looking out for the public's well being but for the good of Edison's company. And even when intentions for a better method of execution are good, as Moran points out, 'no execution can really be considered humane'.

How We Got the Chair

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

In 1890, William Kemmler, a thirty-year-old dimwitted alcoholic, was executed at Auburn Penitentiary in New York. He had hatcheted his lover to death while she did the dishes the year before. He was a nobody, unremembered today but celebrated at the time because he was the first prisoner sentenced to die in the electric chair. Under the terms of the new New York law, the Electrical Execution Act, he got "a current of electricity, of sufficient intensity to destroy life instantaneously" rather than being hung. Kemmler's history, and the often bizarre story of how that first execution came to pass, is told in _Executioner's Current: Thomas Edison, George Westinghouse, and the Invention of the Electric Chair_ (Knopf) by Richard Moran. Moran has found that the problems of adopting this novel method of execution at the time mirror our own problems over capital punishment, because of the universally felt ambivalence on the subject. Although we are all sure that our stances on the death penalty are the right ones, our society acts as if it is not at all sure, and given the recent overturning of capital cases based on DNA testing, it is surely right to be unsure.Electrocution was advocated as a humane improvement over hanging, but it was promoted as commercial propaganda. Electricity was being wired into homes via two systems, the system of direct current advocated and sold by Thomas Edison, and the system of alternating current pushed by George Westinghouse. Edison opposed capital punishment, but realized that making Westinghouse's system the basis for execution would reinforce that it was a dangerous current, unsuitable for customers' homes. Direct current was safe, Edison maintained, but alternating current was "the current that kills." Before the word "electrocution" was coined, as there was no word for executing by electricity, Edison proposed that condemned criminals be "Westinghoused." No amount of his propaganda could have made direct current easy to transmit or easily transformed from high voltage transmission to low voltage home use, but without Edison's efforts, the push to install electric chairs would not have been nearly so strong. Most states eventually switched from hanging, despite the botched electrocutions that revolted observers. Kemmler's was one of these, requiring a couple of jolts before he had ceased breathing, but leaving him frothing at the mouth and stinking up the execution room with the smell of his burned flesh.While there were more successful electrocutions which were quiet, quick, and scentless, no one knew at the time whether the procedure was painless (although many maintained it was), and this is still a matter of some controversy. No one really knows the details of the internal process, and no one lives to tell us if it hurt. Moran's exhaustive book traces the legal acceptance of electrocution in our country, with courts at different levels assuring all that it may have been "unusual" when it was novel,

shockingly good popular history

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

Moran begins with America's first execution using that most peculiar of lethal inventions: the electric chair. The execution sets an appropriate tone for a book that is both a history of that invention and an examination of the search for a humane means of executing criminals: the execution of convicted murderer William Kemmler was a cruel, horrific and botched experiment of an electrocution, and proclaimed a "success" despite all of that."Executioner's Current" lays the groundwork for this interesting story of how the United States came to employ what was supposedly a novel, enlightened, and humane means of execution -- in actuality only novel -- by describing it's origins in the electrification of America and the early competition over what model this would follow: George Westinghouse's AC model or Thomas Edison's DC model. DC was economically inferior and inefficient compared to Westinghouse's AC system. Being unable to compete on the relative merits of the two technologies, Edison launched a public relations and lobbying campaign that would rival any modern effort for its obfuscations and distortions. The object of this campaign was to paint AC as being too dangerous to use in residential or commercial applications.Naturally, when New York state was revising it's capital punishment laws at that time, and electrocution came into the debate as a new, possibly more humane means of execution, they consulted the national hero and genius electrician, Thomas Edison. Edison, in the midst of slandering Westinghouse's more efficient electrical distribution technology, told them that AC was so dangerous that it would be the ideal means to execute criminals. This was followed by staged experiments on animals designed to illustrate how lethal (and how relatively safe DC current) AC current was, the invention of a practical electrical chair, and the many electrocutions that have been performed since.I am not an opponent of the death penalty, but I have always considered the electric chair to be a ridiculous method of execution. Moran's larger point is that the search for a more humane means of execution has little to do with sparing the condemned from suffering, but is more about assuaging the conscience of the persons and larger society that condemned him. To Moran, the more important question than humane means is whether any execution is humane. On this point, I would disagree with him (Moran is clearly an opponent), but the point is one worth making and the question is one worth asking. Between that and the fascinating story, this book is one well worth reading.