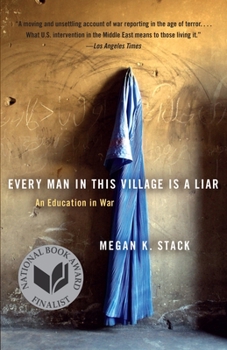

Every Man in This Village Is a Liar: An Education in War

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

A shattering account of war and disillusionment from a young woman reporter on the front lines of the war on terror. A few weeks after the planes crashed into the World Trade Center, journalist Megan K. Stack was thrust into Afghanistan and Pakistan, dodging gunmen, prodding warlords for information, and witnessing the changes sweeping the Muslim world. Every Man in This Village Is a Liar is her riveting story of what she saw in the combat zones and...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0767930347

ISBN13:9780767930345

Release Date:June 2011

Publisher:Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

Length:272 Pages

Weight:0.65 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 5.1" x 8.0"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

KNOWNS AND UNKNOWNS

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

Megan Stack is a journalist, in my own opinion a superlative journalist. Following the 9/11 attacks she was detailed to cover the various situations in the Middle East and wherever we are to locate Afghanistan. She was in her 20's, younger (she tells us) than she realised, and `extremely American'. She disclaims any strong convictions, stating that as a journalist she only `wanted to see'. Well, she has the eyes to see with, she has seen with them, and she has the skill to let us see via them. She does not like any of what she sees, and small wonder. However this set of reports is no kind of tract. She takes us with her to Iraq, Afghanistan, Lebanon, Libya, Egypt, Jordan, Israel and the Palestinian territories, and we accompany her in her attempts to make what sense can be made of it. Mr Rumsfeld once said with admirable clarity that policy analysis had to be based on the known knowns and the known unknowns. There are known to be unknown unknowns, but apart from knowing that much, we can't in the nature of the case feature these in our decisions. Fair enough, but knowing is one thing, and understanding is something else entirely. There are ways of failing to understand plain facts that are looking us in the eye, and they stem from prejudice, patriotism and preconception. There is also often a challenge in trying to make sense of the plain facts, and that, similarly, requires a mind that is not pre-programmed. Megan Stack has the right kind of mind, and at the very beginning and near the end of her book she summarises one of her overall conclusions. The version of this in her prologue is, perhaps, slightly startling. Says she `the war on terror never really existed. It was not a real thing...it was essentially nothing but a unifying myth for a complicated scramble of mixed impulses and social theories and night terrors and cruelty and business interests, all overhung with the unassailable memory of falling skyscrapers.' `Not a real thing' indeed? Professor Bobbitt, where are you now with your long and scholarly Terror and Consent? I can go along with Megan Stack to the extent that the war on terror was more a slogan than a policy, and that to the extent that it was a policy it was a hopelessly incoherent jumble. Whether you agree with me, or with her, or with neither of us, it is undoubtedly the case that the Bush administration in its latter days was resorting less and less to the expression `war on terror', this point made by Bobbitt among others. Whether or not I can go along with Stack's conclusion, I am certainly compelled by her narratives to say to myself `A war on terror sounds fine, but what exactly is it? What are we fighting? Whom are we fighting?' Al Qaeda are at least a known entity, however elusive, but to say the least they are not the whole story. Do you remember Mr Bush's great objective of turning Iraq into a shining city of democracy on a hill, the emanations of which would pervade the region and set it alight with the inspi

"I had to keep on running..." (and writing) "...because I was drowning in shame."

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

The ability to see. And then to report what is truly seen, without the eyes being averted due to "editorial concerns." Can it be taught in journalism school, or is it an innate moral compass one is born with? Initially I was skeptical of this book; the title is a bit off-putting (that was before I learned that it refers to one of world's oldest logic problems; and has ample applications to all involved in the so-called war on terror). And then it was written by a journalist, a woman at that, who was unfamiliar with war when she started. Enough reasons for some justified unease. Fortunately a good friend recommended it; he even wanted to check out the validity of certain portions of the book, those on Saudi Arabia, with me. And so when it popped up on my Vine Newsletter, I had to say: "Yes, please." The best decision I made the entire week. Megan K. Stack is a remarkable person. She had been in Paris on September 11, 2001; soon thereafter she was on the Afghanistan - Pakistan frontier, reporting on the hunt for Bin Laden. She appears to have come to the so-called "War on Terror" unencumbered by theoretical models of the Islamic world formulated in America's various think-tanks and university "Middle East Studies Centers." She espoused none of the theories of the fictional "York Harding," as described in Graham Greene's The Quiet American (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition). Her assignments thereafter carry her to Israel, Iraq, Libya, "Kurdistan," Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Lebanon and Egypt. When she gets "shut out," meaning that she really cannot cut through the government-imposed barriers on journalists, like in the Yemen, she says so. Thought her portrait of the madness in Qaddafi's Libya was on target. In Israel she learns that you cannot call Israelis from Morocco and Yemen "Jewish Arabs." She also commits the ultimate faux pas: "You humanized them. You're writing about suicide bombers as people who have corpses and families. They can't stand to see them written about like that." In Saudi Arabia I saw only one error; it was in assessment and judgment, understandably enough given her brief time in the Kingdom. She is yelled at by two guards for standing in front of the bank; told to go away because men might see her. Stack says: "Leave me alone!" And then she says: "This was a slip. In a land ruled by male ego, yelling at a man only deepens the crisis." Au contraire. In this situation, 98% of the time, the correct response is yelling loud and hard. The chauvinistic men don't know what to do, and slink off. My wife did it several times. It is Iraq and Lebanon that are the essential core of the book, and she tells the story with a rising, Bolero-esque style; certainly not of pleasure, but of horror. The murder of the young female Iraqi journalist, Atwar Bahjat is particularly heart-rending. Call it what you may, incredible courage, sheer insanity, the ultimate in journalistic duty, but the climatic part of the book is in South Lebanon, where Stac

"September 11 stands out now like a depot..."

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

"September 11 stands out now like a depot, the last train station before a vast unknown prairie, where the engine of events groaned and roared and hauled America back into the wilderness. It was the beginning of lost days, of disastrous reaction, of fumbling around the world." That quotation is from the Prologue of Every Man in This Village is a Liar: An Education in War and once I read that paragraph, I knew I would not be able to put this book down. From the Prologue on, I was riveted to every word, at once horrified by what I read and awestruck by the poetic craftsmanship of Megan K. Stack's brilliant writing. I found myself gasping at her shocking reports of the terror, violence, hatred; I cried for the thousands upon thousands of innocent lives, especially those of the children, lost or maimed so savagely and senselessly. Yet I was struck, even captivated by her sensitive metaphoric language. She probes honestly and fearlessly to expose the soft under-belly and true human face of all this war. Beginning with September 11, this memoir represents six years in the life of a young woman war correspondent, chasing combat in America's War on Terror in the Middle East and in her words ~ "pulling poetry out of war". She is fearless and generous with her reporting. She is neutral and objective but still adds a fine touch of woman's sensitivity to her reporting, giving a woman's voice to the darkest and ugliest, most hateful and violent truths of the war on terror in the Middle East. She reports from Afghanistan and Pakistan, Iraq and Jordan, Israel and Egypt, Libya and Yemen, Lebanon and Syria ~ the war ravaged Muslim world where a woman's voice is otherwise squelched except for the howling and wailing of her grief over her dead. Megan Stack's perspective is a woman's perspective but at the same time it is without gender barrier...it is simply human and human in its most raw and naked state. "But up close the war on terror isn't anything but the sick and feeble cringing in an asylum, babies in shock, structures smashed. Baghdad broken. Afghanistan broken, Egypt broken. The line between heaven and earth, broken. Lebanon broken. Broken peace and broken roads and broken bridges. The broken faith and years of broken promises. Children inheriting their parents' broken hearts, growing up with a taste for vengeance." That is the lasting image, the education in war I have taken away from this book. I finished this intense, soul-shaking memoir feeling a little more enlightened about the wars and policies, politics and philosophies I do not understand. The truth is shocking and not easy to take. It is difficult to read and disillusioning. I finished this book disturbed, distressed, and saddened. I wept. I had nightmares. I awoke from troubled sleep last night to some of my neighbors getting an early start on their Fourth of July fireworks, shaking as if I myself were shell-shocked. I wasn't thinking about our American Independence Day a

Truly is "An Education in War" for me.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

I have read many books on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan - books of all types, written by soldiers, journalists, "experts" and more, but never have I read a book that touched me like this one did. The author (a woman of unbelievable courage), concentrates on the toll war takes on innocent civilians, and it is NOT a pretty picture. Despite the author being an excellent writer, I found the book very difficult to read. For the most part, it was heartbreaking, but it also made me feel tremendous anger, and I shared the author's feelings of helplessness many times. I think it should be required reading for anyone who is in a position of power, because if they have a heart at all, the way we wage war would change drastically. As I noted above, I was familiar with much of what goes on in Afghanistan and Iraq, but the author got closer to the actual, innocent people who suffer so much than anyone did in the books I've previously read. I was not familiar with Israel's response to Hezbollah's taking of 5 soldiers, and that, to me, was the most heart breaking part of the book to read, although all of it was more than disturbing. It is hard for me to articulate, or attempt to summarize this book because it contains so much. The stories about elderly people trapped in collapsed houses, with no one to help them, the children and families mercilessly bombed, just for being in the wrong place at the wrong time....the author gets closer to these things happening than any author of any book I have ever read. I learned a lot by reading this book - things I almost wish I hadn't learned, but also things that everyone should know. By now I may have become a bit de-sensitized by the horrows of Iraq and Afghanistan, but I was truly shocked and revolted by what Israel did to Lebanon, and the Lebanese people. The author makes the people and the events so real and so powerful that the emotion just poured out from me - the tears and anger were things I don't think have ever happened to me while reading a book. All I can really say is that you have to read it for yourself - and everyone should.

"You can survive and not survive, both at the same time."

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

In September 2001, Megan K. Stack, then a 25-year-old journalist with the Los Angeles Times, was in Paris. After 9/11 she was thrown into a journalistic breach and sent to Afghanistan. That happenstance introduced her to the War on Terror and a harrowing six years of reporting on that War, as pursued in Afghanistan, Israel, Lebanon, and Iraq, with side-trips to Libya, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and Egypt. EVERY MAN IN THIS VILLAGE IS A LIAR is her memoir of those six years, her account of some of the incidents and experiences more indelibly seared on her memory. The value of the book lies not in its analysis. For Stack, the War on Terror defies analysis; indeed, it defies comprehension. In her Prologue, she writes: "Only after covering it for years did I understand that the war on terror never really existed. It was not a real thing. Not that the war on terror was flawed, not that it was cynical or self-defeating, or likely to breed more resentment and violence. But that it was hollow, it was essentially nothing but a unifying myth for a complicated scramble of mixed impulses and social theories and night terrors and cruelty and business interests * * *." So don't look to this book for calm, measured analysis. Its value, instead, is its anecdotal eyewitness reports of sundry events whose only cohesion is as a relentless parade of madness and mayhem. The book is episodic, so that the overarching picture, to the extent there is one, is in the nature of a surrealistic mosaic, perhaps a 21st Century version of Peter Bruegel's painting in the Prado, "The Triumph of Death". Stack's writing is decent, but not always graceful. Too many of her metaphors are awkward. ("A plane lumbered overhead, slicing white blood from a bright winter sky." "Day creaked up slowly over the hills, and the city lay swaddled in the gentle ache of sleeplessness.") Her writing is not particularly disciplined or logical. But then neither is her subject. What is the source of the book's title? As Stack prepared to embark on her sojourn of the modern circles of hell, someone in Pakistan told her "Every man in this village is a liar". It was a sardonic twist on the ancient Greek paradox ("All Cretans are liars"), in which the traveler realizes that if the villager he encounters is telling the truth, then he's lying, but if he's lying he must be telling the truth. And it's not just individuals: what seems to characterize the Middle East and the War on Terror is that every nation and political group involved is lying. One example: Late one night in Afghanistan Stack interviewed some of the civilian survivors of an isolated hamlet that had been crushed by U.S. bombing and wrote and filed a story about it. The next morning she awoke to find that the Pentagon had labeled her story "false". Donald Rumsfeld explained, "one ought to be sensitive to how difficult it is to know with certainty, in real time, what may have happened in any given situation in A