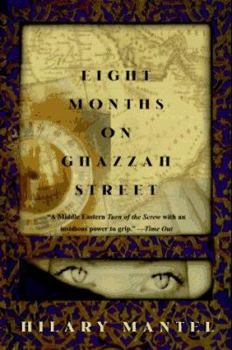

Eight Months on Ghazzah Street

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

When Frances Shore moves to Saudi Arabia, she settles in a nondescript sublet, sure that common sense and an open mind will serve her well with her Muslim neighbors. But in the dim, airless flat,... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0805052038

ISBN13:9780805052039

Release Date:July 1997

Publisher:Holt McDougal

Length:288 Pages

Weight:0.75 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 5.5" x 8.2"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

No Freedom of Information

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

This book isn't about Saudi Arabia; it's about the psychological impact of living in an informational vacuum. Jeddah is a place to experience extraordinary cultural diversity, to delve deeply into Islam, to immerse oneself in history and architecture, to have mindless fun, or to withdraw into the shadows as Frances Shore did in Mantel's novel. But however you as a Western expatriate "see" the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, you can be certain that your view is highly superficial, that all of the important decisions that affect your life in The Kingdom are made by people behind closed doors, speaking Arabic, thinking of you as a non-Moslem non-person. You may be useful to them for 1 year or 18, but ultimately you - and all of the other expats who work there from around the world - are expendable. You have no right to know anything, no right to appeal decisions with which you disagree, severely limited freedom of movement within the country, no right to leave the country until the faceless organization that took your passport the moment you arrived chooses to return it to you. You have no control over your own life except in the most superficial sense. Some people cope with these constraints better than others; Frances Shore is one of many who can't cope with them at all, and becomes increasingly terrified and paranoid as she realizes the depth of her ignorance and powerlessness. Those who read the novel in search of a clear resolution to the mystery simply miss the point. Clear resolution presupposes access to information, and power to use it. Western expats in Saudi Arabia have neither.

Lost in Jedda . . .

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Mantel's book brings to mind the films "Blow-Up" and "The Conversation," in which evidence of some kind of malfeasance is discovered by an otherwise innocent observer, then takes on a life of its own, while the observer is swept up in a growing tide of paranoia. The narrator in this chilling novel is a woman whose husband has taken a job in Jedda, Saudi Arabia, in the 1980s. Husband and wife are immediately submerged in a culture far different from any they've known, where appearance and reality are seldom clear and fear and rumor dominate their lives. Trapped in the claustrophobic flat provided by her husband's employer, the narrator comes to suspect that the empty flat above her is not empty at all. Looking for clues to the real nature of its use, she comes to know the wives of two other men who live in the building, who try to dismiss her concerns while reassuring her that the restrictive role of women in this Muslim country is quite reasonable, and repeating to her firmly held beliefs about the West that are wild exaggerations and outright myths. As suspicion points in every direction, the reader begins to doubt the veracity of everyone, including the other western expatriates who make up the central character's social circle. Finally, the novel is a discourse on the impossibility of discovering the truth, especially when covering it up or ignoring it serves the interests of enough people. Meanwhile, it finds much to say about gender politics, whether under the dictates of Islam or the double standards still to be found in the democratic West. This is a page-turner that is also sharply written. Its characters are vividly created and the dialogue among them is often withering. Not likely to be embraced by Saudi readers, it portrays the Kingdom in ways that are far from flattering. Readers of this book may also be interested in Peter Theroux' memoir, "Sandstorms: Days and Nights in Arabia."

With all the veils, few know what is really going on.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

With remarkable understatement, a fellow airline passenger tries to prepare Fran Shore for her life as an expatriate wife in Saudi Arabia. A cartographer by profession, she is told, "You're redundant. They don't have maps." As Mantel unfolds the action, and lack of action, which take place in the apartment complex where she lives, and in the business community, Fran cannot help but try to create mental maps to make sense of the culture that has enveloped her. Bored and frustrated, she is unable to discover what is really happening in the "empty" flat upstairs, unable to understand the lives which her devoutly Muslim female neighbors accept as completely normal, and so overwhelmed that she wonders, "Am I visible?" And that, perhaps, is the point. She IS visible in a heavily veiled world, destined never to comprehend fully either the daily lives or culture of her hosts, a culture within which she has tried, unsuccessfully, to maintain her own values. As Fran leaves the flat in which she has spent eight months, neither she nor the reader will ever know completely what has happened in the "empty" flat above or in the now empty flats once belonging to her friends. She is forced to accept at last the comment of an Arab acquaintance, "The Kindgom is not a logical world, and besides, logic is not an ornament of young ladies." Mary Whipple

Transported me to another world!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 25 years ago

This novel transported me into another world and into the mind of a woman who inhabited it. I think it is irrelevant that we never know exactly what happened--we are able to better understand the unravelling of Francis Shore. I loved this work so much that when I was halfway through the novel, I stared over. I didn't want it to end.

"Funny place, Jeddah. Nobody knows half of what goes on."

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 27 years ago

"The Kingdom is not a logical world." July 24, 1997 With remarkable understatement, a fellow airline passenger tries to prepare Fran Shore for her stay as an expatriate wife in Saudi Arabia. A cartographer by profession, she is told, "You're redundant. They don't have maps," an observation which Fran quickly discovers to be correct-she is redundant, irrelevant, and unimportant in this culture, and there is no way for her to participate in this closed society. With her social life limited almost exclusively to her apartment complex and the foreign business community, Fran writes in her diary, trying to make sense of the culture which envelops her Unable to participate in the world belonging to her Muslim neighbors and unable to explore Jeddah on her own, Fran, bored and frustrated, finds herself fixating on the mysterious activities and strange, painful noises emanating from the supposedly empty apartment above her. Her female Muslim neighbors seem to accept this mystery without any sense of curiosity, and, to her dismay, she can discover nothing about what's happening up there, despite her growing horror at what she suspects is happening. Overwhelmed by unanswered questions and by the restrictions on her life, Fran wonders, at one point, "Am I visible?" And that, perhaps, is the point. She IS visible in a world which values veils, a woman who does not fit into the culture, destined never to comprehend fully the daily lives of her hosts. Soon the mystery of the flat upstairs and the growing number of empty flats around her assume symbolic significance. Mantel is masterly at creating a sense of place, not surprising since she lived in Saudi Arabia for four years, and with a sharp eye for detail, she creates a devastating portrait of the lives of Saudi women. With a sense of detachment, she also portrays Fran as a foreigner who means well but has no idea of how she is regarded by the Saudi women who are her neighbors. The novel is darkly humorous, and consummately ironic, especially in its conclusion. A fascinating book filled with ambiguities and the differences of perception which arise from different cultures, Eight Months on Ghazzah Street takes a close look at life in Jeddah as it is seen both from the inside and from the outside, and shows the reader that "The Kingdom is not a logical world, and besides, logic is not an ornament of young ladies." Mary Whipple