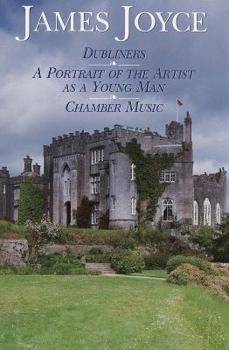

James Joyce: Dubliners, a Portrait of the Artist as a Yong Man, Chamber Music

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

An eclectic volume of works by one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century includes a short story collection, his most famous novel, and an early sequence of poems. This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:051708239X

ISBN13:9780517082393

Release Date:August 1995

Publisher:Gramercy Books

Length:158 Pages

Weight:1.69 lbs.

Dimensions:1.6" x 6.4" x 9.3"

Related Subjects

Classics Criticism & Theory Fiction History & Criticism Literature & Fiction Love Poems PoetryCustomer Reviews

5 ratings

One of the milestones of 20th century literature

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

One of the great changes in literature in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was the birth of autobiographical literature. Even at the end of the 19th century, it was very unusual for any writer to make one's own life the basis for a purely literary work. To be sure, Dickens had put much of the London he knew in his youth into his novels, but there is no Dickens novel that can be described as purely autobiographical. Mark Twain had written memoirs that employed novelistic techniques and Samuel Butler put much of his own life into THE WAY OF ALL FLESH (a novel written in the early 1870s but not published until 1903), but it was only with such works as D. H. Lawrence's SONS AND LOVERS (1913) and James Joyce's PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST AS A YOUNG MAN in the English-speaking world and Marcel Proust slightly earlier in Paris that authors began taking their own lives as material for works of fiction. In Lawrence's SONS AND LOVERS, a host of real life characters and actual life experiences became characters and scenes in novels. Likewise, most of the events of PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST were based on actual events. It isn't quite autobiography, but neither is it pure fiction. Because the genre of fictionalized autobiography has become such a common literary form in the century that has followed Proust, Lawrence, and Joyce's work, the importance of this work can hardly be overestimated. PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST is important also for the innovations Joyce made in narrative. While the events in the story occur along a time line, Joyce is not particularly concerned with most of the details in the timeline. The narrator is not concerned to tell a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end, but instead wants to present a series of prose snapshots from various periods in the life of Stephen Daedalus, who is transparently based on Joyce himself. The narrator lays out the events, but he isn't concerned with explaining them or making them clear. There is, in fact, little or no interaction with the reader. Most narration presupposes the presence of the reader, but PORTRAIT ignores any reader. This leads to a certain coolness in the prose that some find discomfiting. What cannot be denied is the brilliance and the genius of the prose. It is a prose that alters and matures gradually with the central figure of the tale. The first pages border on baby talk, while the final pages are as mature as Daedalus at the same age. In terms of form and execution, this is easily one of the most brilliant works of fiction of the past century. Moreover, it is a remarkably accessible work. For those who first come to Joyce through the agony of reading some of the more stressful sections of ULYSSES or, worse, FINNEGAN'S WAKE, read PORTRAIT will come as something of a shock. Compared to ULYSSES, this is remarkably easy going. The complaint that I hear some make of the book is that nothing happens. That is true, if by "happens" one means an interestin

the edition to get

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

If you're gonna buy a copy of "A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man," you can't go wrong with the Wordsworth Classic edition. Its advantages are several: 1. It's extremely cheap. 2. It features a very long and immensely insightful (32-page) introduction by Jaqueline Belanger, which includes a biography, publishing background, sections on language structure, irony, etc. There are also many suggestions for further syntopic or critical reading. 3. The thing is complete and unabridged. 4. There are extensive footnotes at the end, which are keyed throughout in the text, explaining all the Latin and the extinct realia of Joyce's world. In short, get it. As for the work itself, it's a very good prepper for "Ulysses:" I started that novel without having done this one. Later I came back to this: much was made clearer. Don't make my mistake.

A Delicious Read!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

"A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man" is an impressionistic, semi-autobiographical work in which Joyce, through the character of Stephen Dedalus, relates the events and impressions of his youth and young adulthood. The novel flows effortlessly from Stephens first memories as "baby tuckoo" to his final journal entries before embarking on a promising literary career in Paris. In the pages between, Joyce's virtuosity of prose explodes in passages with frightening intensity. Even those who dislike Joyce's confusing, sometimes-infuriating style, should be awestruck by his undubitable writing ability.However, as anyone reading this review should already know, despite his virtuosity, Joyce is not for everyone. He is simultaneously one of the most beloved and despised writers of the twentieth century. For those of you who are unfamiliar with his work and hesitantly contemplating becoming acquainted with it, here is some food for thought: first, start with "Portrait," it is far more accessible than his subsequent works and a better introduction to them than the also-excellent "Dubliners" is. Second, do not try to judge "Portrait" by the same standards as other books. Joyce is not trying to tell an amusing story here, he is trying to relate the impressions of a young man torn between two existences: a religious or an aesthetic. If you are a meat-and-potatoes type of reader, meaning the kind of reader who prefers a "story," Joyce will not be your cup of tea. Lastly, Joyce's reputation perhaps does his works injustice. Yes, he is extremely encyclopedic and takes on many themes in his works. But perhaps too many readers get sidetracked from the aesthetic merits of his works by concentrating solely on the intellectual values. It is his prose which can be universally appreciated, whether you understand the ideas it portrays or not. His prose is his bread-and-butter. Some people pompously brag of their "getting" Joyce without actually appreciating what he does. I don't claim to be a bonafied Joyce scholar, but it is my experience that to enjoy Joyce is to appreciate "literature for literature's sake." If you enjoy literature, poetry or prose, than you should enjoy the style with which Joyce writes, that is to say, all styles. And he has seemingly mastered all styles. That is not to say that the many thematic levels in which his novels succeed are to be ignored, for their expression is not seperate from the means with which Joyce does it, but congruous with it.To read Joyce is to revel in the limits of artistic creation and then to read on as the limits are then stretched further.Bon Apetite!

Not easy but well worth the effort

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

I've seen some reviews that criticize the book for being too stream of consciousness and others for not being s.o.c. enough. The fact is, for the most part it's not s.o.c. at all. (See the Chicago Manual of Style, 10.45-10.47 and note the example they give...Joyce knew how to write s.o.c.). A better word for A Portrait is impressionistic. Joyce is more concerned with giving the reader an impression of Stephen's experience than with emptying the contents of his head. What's confusing is the style mirrors the way Stephen interprets his experiences at the time, according to the level of his mental development. When Stephen is a baby, you get only what comes in through the five senses. When he is a young boy, you get the experience refracted through a prism of many things: his illness (for those who've read Ulysses, here is the beginning of Stephen's hydrophobia - "How cold and slimy the water had been! A fellow had once seen a big rat jump into the scum."), his poor eyesight, the radically mixed signals he's been given about religion and politics (the Christmas meal), his unfair punishment, and maybe most important of all, his father's unusual expressions (growing up with phrases like, "There's more cunning in one of those warts on his bald head than in a pack of jack foxes" how could this kid become anything but a writer?)It is crucial to understand that Stephen's experiences are being given a certain inflection in this way when you come to the middle of the book and the sermon. You have to remember that Stephen has been far from a good Catholic boy. Among other things, he's been visting the brothels! The sermon hits him with a special intensity, so much so that it changes his life forever. Before it he's completely absorbed in the physical: food, sex, etc. After it he becomes just as absorbed in the spiritual/aesthetic world. It's the sermon that really puts him on the track to becoming an artist. One reviewer called the sermon overwrought. Well, of course it's overwrought. That's the whole point. Read it with your sense of humor turned on and keep in mind that you're getting the sermon the way you get everything else in the book: through Stephen. After Stephen decides he doesn't want to be a priest, the idea of becoming an artist really starts to take hold. And when he sees the girl on the beach, his life is set for good. That scene has to be one of the most beautiful in all of literature. After that, Stephen develops his theory of esthetics with the help of Aristotle and Aquinas and we find ourselves moving from one conversation to another not unlike in Plato (each conversation with the appropriate inflection of college boy pomposity). In the end, Stephen asks his "father" to support him as he goes into the real world to create something. I like to think that this is an echo of the very first line in the book. The father, in one of many senses, is the moocow story. The story gave birth to Stephen's imagin

Unfortunately, a rarity

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

James Joyce is one of the very few writers (John Steinbeck is another) who realizes what can be accomplished with the act of writing and achieves it. Certainly, some people may be lacking interest in this book, but the reason it is such a classic is because it pulls off things most books never even try to do. The simplest of events are described exactly as Joyce sees them, and he does not try to make them "interesting" or "exciting". He sees things for what they are and presents them without total honesty. Reading "Portrait" is like reading a picture, with every detail brought to light. Those who find it boring should not blame their blindess on what they cannot see.