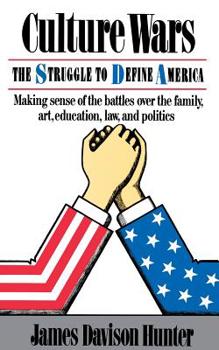

Culture Wars: The Struggle To Control The Family, Art, Education, Law, And Politics In America

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

A riveting account of how Christian fundamentalists, Orthodox Jews, and conservative Catholics have joined forces in a battle against their progressive counterparts for control of American secular culture.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0465015344

ISBN13:9780465015344

Release Date:October 1992

Publisher:Basic Books

Length:432 Pages

Weight:0.92 lbs.

Dimensions:1.1" x 5.3" x 8.1"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Culture Wars

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Few of us, I think it's safe to say, question the truism that contemporary culture chatters like an activated geiger counter, emitting danger signals, signs of ominous decay if not collapse. But finding thoughtful analyses (rather than off-hand journalistic impressions) of the situation is frequently difficult. So James Davison Hunter, a sociologist at the University of Virginia, rendered us sizeable service in Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America (New York: Basic Books, c. 1991). Davison begins his book with some pointed portraits of American citizens deeply divided over such issues as abortion, homosexuality, and public school curricula. On both sides (folks he labels "orthodox" and "progressive") of such issues you find passionately committed individuals who, un¬for¬tunately in Davison's view, generally hurl anathemas rather than listen to each other. Indeed, they generally "talk past" (p. 131) each other. The issues are important! They merit passion! "But these differences are often inten¬sified and aggravated by the way they are present¬ed in public" (p. 34). They need to be honestly discussed lest they divide this nation's body politic, for "At stake is how we as Americans will order our lives together" (p. 34). You suspect Davison fears this nation might divide, as it once did in the Civil War, over irreconcilable moral positions. The chasm dividing the nation is easily discerned. There are the "orthodox" and the "progressives." Folks committed to "orthodoxy," Davison says, share an allegiance to "an external, definable, and transcendent authority" whereas those committed to "progressivism" embrace modernity and tend "to resymbolize historic faiths according to the prevailing assumptions of contem¬porary life" (pp. 44-45). For example, "orthodox" persons generally label premarital sex "morally wrong" whereas "progressives" often condone it. These moral and religious convictions are increasingly influencing the political agenda--as was evident in the 1992 Republican Convention. Indeed, one survey found "that the relative embrace of orthodoxy was the single most important explanatory factor in sorting out variation in the elite political values," counting for more than such things as "social class background, race, ethnicity, gender, the size of the organization they work in, and the degree of pietism by which they individually live" (p. 97). Consequently, you increasingly find "orthodox" Protestants feeling more akin to "orthodox" Catho¬lics and Jews than to "progressives" in their own "household of faith." Denominational loyalties have rapidly eroded--something most of us (at least on college campuses) have noted. Concurrently, there have appeared a multitude of special-interest and critical-cause para-church organizations. One the one side you find James Dobson's "Focus on the Family," while on the other side you find Norman Lear's "People for the American Way." They've mastered the technique

A Prescient Analysis of the Current Liberal/Conservative Landscape in America

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

James Davison Hunter, a professor of sociology and religious studies at the University of Virginia, appears prescient in this 1992 book about the emergence of a religious conservatism in the United States that will dominate the political agenda through its emphasis on certain traditional values. He frames this as a "culture war" over the meaning of America and its place in the world. He found that the many battles over the arts, women's rights, gay rights, history, science, and a range of other issues were the canaries in the mind shaft for a realignment in American culture that emphasized moral and religious concerns. Of course, Hunter wrote this book long before the election of George W. Bush in 2000 and the resultant dominance of these issues on the national stage. Hunter concludes that the debate in this culture war revolves around--rather than stances on Jesus Christ, Luther, or Calvin--on how one reacts to the ideas of Rousseau, Locke, or Voltaire (including their philosophical heirs, especially Nietzsche and Rorty). "The politically relevant world-historical event, in other words," Hunter writes, "is now the secular Enlightenment of the eighteenth century and its philosophical aftermath. This is what inspires the divisions of public culture in the United States today" (p. 132). He also notes that "what is ultimately at stake is the ability to define the rules by which moral conflict of this kind is to be resolved" (p. 271). Hunter believes that "the culture war is rooted in an ongoing realignment of American public culture and has become institutionalized chiefly through special-purpose organizations, denominations, political parties, and branches of government....In the end, however, the opposing visions become, as one would say in the tide though ponderous jargon of social science, a reality sui generis: a reality much larger than, and indeed autonomous from, the sum total of individuals and organizations that give expression to the conflict. These competing moral visions, and the rhetoric that sustains them, become the defining forces of public life" (pp. 290-91). He does not see this culture wart as something that will eventually reach a balance; a rationally balanced negotiated settlement of the conflict does not seem possible. Instead, Hunter believes that one side or the other will gain the upper hand and dominate the culture. "The principal reason," he contends, "is that the most vocal advocates at either end of the cultural axis are not inclined toward working for a genuinely pluralistic resolution" (p. 298). In terms of who has the edge toward victory in this culture war, Hunter thinks "the moral vision of the orthodox alliance, particularly as championed by the Evangelical Protestant community, is in a strong position to actually dominate American public discourse in the near future" (p. 299). This is because they bring a passion and organization to the fight not present on the other side. Despite the resources and power of

A wide-angle view on American society...

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Though the book was published originally published in 1991, it is no wonder that this book is still in print: it is as relevant as ever - and I daresay its relevance is increasing again. In this book, Hunter gives us a wide-angle view of what is going on in American society since the second half of the twentieth century. Hunter argues that there is a culture war going on. Consequently, he aims at describing the historical and socio-political backgrounds of this cultural conflict. In five parts, Hunter introduces the culture war (prologue and chapters 1 and 2), maps the lines of conflict (chapters 3 and 4), describes the means of the warfare: the discourse and technology (chapters 5 and 6), and extensively describes the fields of conflict: family, education, media and the arts, law, and electoral politics (chapters 7-11), and finally points out possibilities for a resolution (chapter 12 and the epilogue). Hunter defines a cultural conflict as "political and social hostility rooted in different systems of moral understanding" (42). According to Hunter, the culture war in America revolves around different worldviews, "our most fundamental and cherished assumptions about how to order or lives - our own lives and our lives together in this society" (42). The contemporary culture war is "a struggle over national identity - over the meaning of America, who we have been in the past, who we are now, and perhaps most important, who we, as a nation, will aspire to become in the new millennium" (50). Though Hunter acknowledges that the culture war is fought out mainy by the elite and 'knowledge workers', this cultural conflict intersects the lives of most Americans, because the conflict has an impact on every institution of American society: family, education, media, law, and politics. Hunter writes brilliantly, avoiding jargon as much as possible and defining many concepts with exceptional clarity. This book is really an excellent read. A personal note: I am a European citizen and often quite puzzled by what is going on in America. This book gave me a really good perspective on the backgrounds of some American discussions, such as Intelligent Design and why the evolution-creation struggle constantly revolves around education textbooks. Moreover, this book also made me realize that in contemporary Europe there are plenty of signs that, perhaps, a European culture war is at hand... An eye-opener, most definitely!

Why the culture wars continue?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

This was a textbook for me in seminary. I am in a conservative Presbyterian denomination and studied at a very conservative seminary, and this book got some interesting reviews from the students. For me, it was a little difficult, since I don't have much background in sociology, but as I trudged through it I really grew to appreciate it. Some of my other classmates loved it too, but there were several who were quite taken aback by it. They didn't like it because Hunter didn't come out and condemn those who were on the wrong side of the culture wars. But that is just the point - in this book he does not try to point out who is wrong and who is right, his object is to demonstrate why neither side is able to persuade, or prevail against the other. Each side in the culture war has it's own set of presuppositions and assumptions that it speaks from. Because of this, that which seems most persuasive to one side completely misses those on the other side, because they don't share the same presuppositions. We are talking past one another. Another problem that Hunter addresses is the issue of extremes and inflammatory rhetoric. Hunter says that, by and large, the culture wars are being fought by people on the extreme ends of their positions. So, the battle of the culture wars is usually fought with inflammatory rhetoric that doesn't persuade, it just angers. As a sidenote I recently read a story about how communists used to train their young recruits. This particular communist said that when a young person adopted communism the best thing they could do was immediately set them on a street corner passing out communist leaflets. They would get attacked mercilessly, but this attack would only serve to harden and solidify the young communist in his or her beliefs. I think Hunter shows this - the inflammatory rhetoric used by those on the extreme ends of the culture war debates, only serves to harden the other side in their respective positions. So, if you are looking for quick answers, or a strategy to defeat your opponents, you won't find it here. But, if you are willing to begin to at least try to understand your opponents, as well as the larger issues, this is a great place to start.

Accessible, Insightful Sociological Research

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

The most significant contribution of James Davison Hunter's Culture Wars resides in the controversy and extensive scholarship that followed the publication of his book. In this work Hunter examines the discourse and methodologies of contempporary social movement organizations, and arrives at an interesting conclusion: while denominational differences may have declined in the second half of the 20th century, significant struggles within the realm of religion remain. The main divide that the author focuses on is that between the "orthodox" and "progressives." While the author does an admirable job of making connections between politics, religion, and social movements, his final anaylsis seems a bit simplistic. Hunter suggests that most of the current debates within American public culture can be expressed as struggles between two monolithic groups. However, other authors who have responded to Hunter's work have taken issue with this point, arguing that in terms of attitudes toward economic justice, the alignments that Hunter describes do not hold. In general, Hunter has provided an accessible, provocative account of contemporary conflicts in the public realm. His conclusions about what these conflicts mean for the future of American democracy are also quite insightful. The main limitation of the work is that his analysis may be overly simplistic, with not enough attention paid to the nuances of the debates that he describes.